Thursday, February 3rd, 2011

by Carolyn Yeager

copyright 2011 carolyn yeager

The activities of the Irgun dominate Wiesel’s life and attention in 1948.

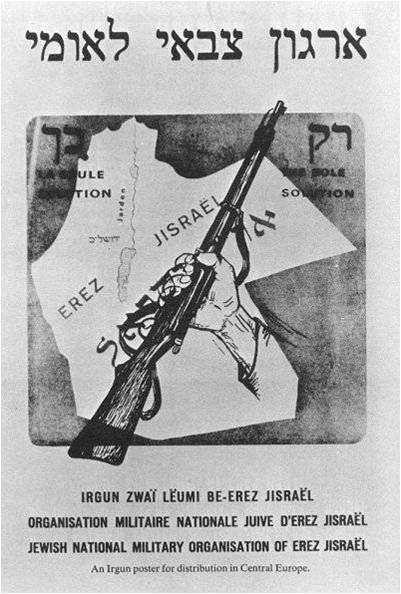

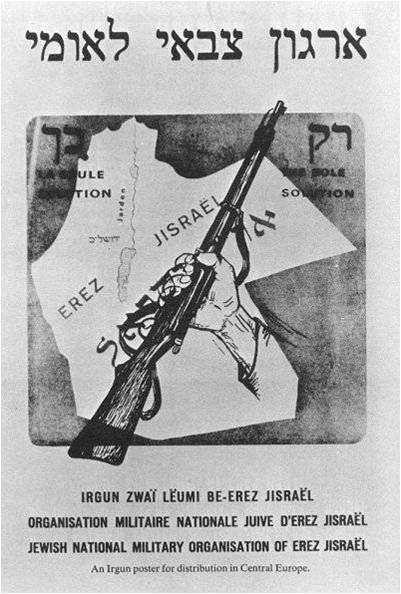

This propaganda poster, with the Hebrew words “This Way Only” on the artwork, was for distribution in central Europe. It was designed in 1937 by the wife of a Polish reserve officer who was working with Irgun representatives. [See story below: Irgun in Central/Eastern Europe] The entire area was called Eretz Israel and was claimed for a future Jewish state.

Dear Readers, As it has turned out, there is much to relate about this one year of 1948 before we get to Elie’s travels. Therefore, I ask for your patience once again. When we left off in Part I, he had just gone to work for the Irgun newspaper, Zion in Kamf. It was November 1947. Here is how he describes his vision of the underground “resistance” at this time.

Physical courage, self-sacrifice, and solidarity could be found even in the lower depths; total compassion, rejection of humiliation either suffered or imposed, and altruism in the absolute sense were found only among those who fought for an idea and an ideal that went beyond themselves. Nobility of action was found only among those who espoused the cause of the weak and oppressed, the prisoners of evil and misfortune. 5

Strangely, this sounds like the “ideas and ideals” of the National Socialists in Germany in the 1920’s who sought the way to lift themselves out of the humiliation and extreme economic hardship imposed on them by the Versailles dictate. But to young Wiesel, the only suffering worth seeing or talking about was that of the Jews. He had not a thought or concern about the native people in Palestine and what was happening to them, just as the Jews of the previous inter-war generation had no concern for the Germans they were exploiting. These others, for him, could not be seen as the “weak and oppressed,” but only as the new enemy that must be overcome by whatever methods were necessary. To Wiesel, even in his youth, only the Jewish militant fighters were “noble” when they carried out their tough and “necessary” actions.

Wiesel admits that by going to work for the Irgun in Paris he was: “risking neither death nor imprisonment. Even deportation from France was unlikely. Stateless persons were rarely deported, that was one of the few advantages of the status.” (Rivers, p162)

This again brings up the question of why Wiesel didn’t seek to become a French national. His sister Hilda had done so. Could it be that his underworld advisors were keeping open where he would be most useful? And as he himself said, being stateless had its advantages – useful for someone working on the fringes of illegality. Here’s how he describes his introduction to the Irgun.

The following Monday I presented myself at the editorial office. Joseph, the boss, showed me to a desk, handed me an article in Hebrew, and asked me to translate it. The article, published in the Irgun’s newspaper in Israel, was a denunciation of David Ben-Gurion and the Haganah and a paean to Menachem Begin, commander in chief of the Irgun. I translated the Hebrew words into Yiddish without grasping their meaning. I knew that the Haganah was fighting the British as hard as the Irgun was, and I couldn’t understand why the two movements hated each other so much. The article also mentioned the Lehi (the so-called Stern Gang), but what was its role? [p163]

I don’t think, after having two “best friends” working for the “resistance” [François and Kalman] and reading everything in the newspapers about the events in Palestine during the past year or two, that Wiesel is being entirely honest when expressing such naivete about the disputing militant factions. Continuing:

The article talked about a certain “season” during which atrocious acts were allegedly committed by the Jewish political establishment. I didn’t dare ask Joseph about this.

“I didn’t dare” brings to mind another passage he wrote on pages 229-30 describing a visit to his sister Bea in Canada. “I desperately wanted to ask her a question that had haunted me for years. What was it like before the selection, those final moments, that last walk with Mother and Tsipouka? It was the same with Hilda. I didn’t dare.”

May I suggest “I didn’t dare” is cover for the real reason—he doesn’t want an answer so that he will not know. And they – Bea, Hilda and Joseph – will be released from telling him something he will have to forget, or lie about. By not daring to know, he can remain blissfully naive about things that “happened, but weren’t real.” Or, were real but never happened?

Oddly, Wiesel’s mystic-mentor Shushani was also caught up in the Jewish assaults in Palestine:

Though he abhorred violence, he was hardly indifferent to the Jewish struggle in Palestine. Whenever the British arrested a member of an underground organization, Shushani tried to get information about his fate. One day he seemed extremely agitated. He interrupted our lesson, pacing, bumping into walls, blowing his nose, panting and wiping his forehead … It was the day a member of the Lehi and a member of the Irgun committed suicide together just a few hours before their scheduled execution. [p164]

I have had the suspicion that Shushani—the expert on the mysteries of life, the illumined one—also had connections to the Zionist intelligence network. Here we learn from Wiesel that he was so partial to the Jew’s fortunes in Palestine that he practically went into hyperventilation when two Jews met their death! Or is that just a typical rabbinic reaction, based on the belief that one Jewish life is worth a million Arabs. Think of the irony, though—that the British were executing Jews who were fighting against them in guerrilla uprisings, just as the Germans had done to Jews fighting as illegal guerrillas against their soldiers. I wonder if the wise Shushani could explain to me the difference?

Now, Wiesel wades in even deeper:

How and why did François suddenly decide to join the struggle for an independent Jewish state? Had he, too, knocked on the Jewish Agency’s door on the Avenue de Wagram? Though he joined the Lehi, and I belonged to the Irgun, our friendship was unaffected. In any case, each of us kept his activities to himself. We both agreed that the less we knew about each other, the better.6 No one asked questions at the synagogue I attended on the Rue Pave’e. To them I was a student like any other. If only they knew. [p165]

Wiesel is conscious of a separation between himself and ordinary people, even other Jews who would naturally be aware and following what was happening in Palestine with great interest and concern. He has gone much farther, and is actually working for those in the “lower depths” of the bloody struggle taking place. Another strange phrase is “I belonged to the Irgun.” In his signature manner, Wiesel covers up his true identity and objectives, but reveals them in the words that pop out unawares. I have commented about the psychological aspects of this trait among criminals elsewhere. So many luminaries of the “resistance” funneled through his office every day that he, by any measure, has to be considered something of an insider within the Irgun.

Above: Henry Bulawko, according to Wiesel one of his fellow camp survivors and an Irgun associate.

Haganah soldiers pose in 1948.

Through work I met Shlomo Friedrich, the leader of Betar, Jabotinsky’s Youth Movement. He was a tall, vigorous man with a rapid gait, a former prisoner in the Gulag.7 […] The process of becoming a journalist involved attending press conferences, public meetings, and demonstrations, and offered a chance to meet such “colleagues” as Henri Bulawko.8 As we talked, we discovered that we had been in Auschwitz-Buna at the same time. And I met Leon Leneman, one of the first to sound the alarm for Soviet Jews. […] Envoys from the Irgun came to the editorial offices every day. All were from Palestine and I was supposed to know only their aliases. Their commander, Elie Farshtei, was shrouded in mystery, but, after swearing me to secrecy, Joseph told me of an incident from his past. In 1946 … he was captured and tortured by agents of the Haganah […] I was flattered when Elie Farshtei stopped by to ask whether I wasn’t working too hard, whether my studies weren’t suffering. I told him that everything was fine, and that I hoped he was pleased with my “contribution” to “Zion in Struggle.” […] In the corridors I might have encountered a young Jewish girl from Vienna, beautiful and daring, who transported documents and provided a hiding place for guns: my future wife.9. [p166-7]

Elie was in deep admiration for all these and many other fighters. No “Nazi” could be more in thrall to the leaders of his movement. He tried to ingratiate himself and win their approval. There is never a hint of concern or questioning about the damage inflicted on non-Jews, of the “human rights” of the native Arab inhabitants. He mentions only Jewish casualties. “A wave of terror swept over the Jewish communities in various Arab countries.” A synagogue was burned, “dozens of Jews were slaughtered in Aden, Jerusalem was besieged” and “gangs loyal to the grand mufti, the pro-Hitler Haj Amin el-Husseini (former ally and protégé of Himmler), attacked Jewish villages and convoys.”

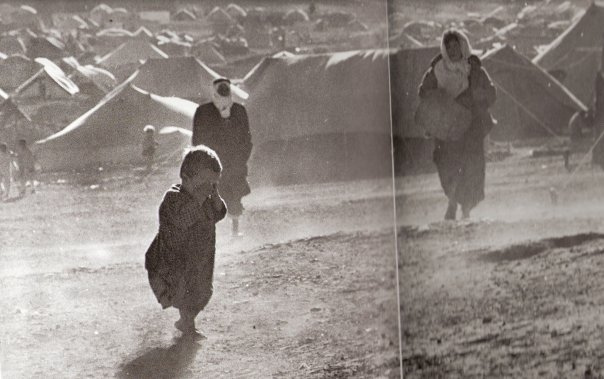

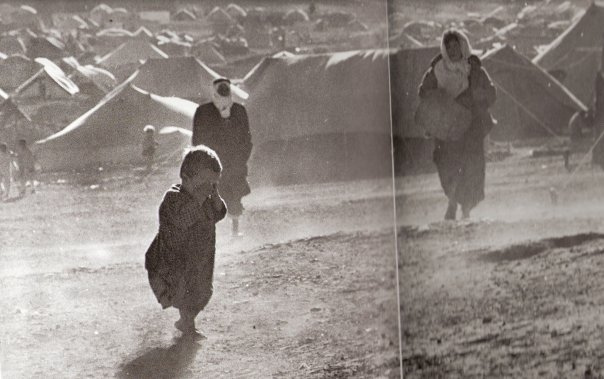

May 15, 1948: Beginning of a 62-year exile for 750,000 Palestinians

Tent city in Palestine, 1948

It would soon be May, and the day of independence. Mobilized units of the Haganah, the Palmach, the Irgun, and the Stern Gang united their efforts and their wills. It was imperative to protect every kibbutz, every settlement. The Zionist organizations in the Diaspora worked tirelessly to supply our brothers in Palestine with political and financial support. In France and in the United States as well, we were mobilized. Young and old, rich and not so rich, all felt the fever our ancestors had known in antiquity. Representatives of all the resistance groups worked day and night, though separately, procuring arms and ammunition, raising funds, recruiting volunteers who would set out for the various fronts of the nascent Jewish state. Elie [Farshtei] and his aides no longer found time to sleep. Out of solidarity, neither did we. [p167]

Excitement! All Jews, all over the world, were involved. Wiesel approved 100%, including the procuring of arms and ammunition. In spite of the fact that it was illegal, the “fever of our ancestors” justified it. You might be wondering why Wiesel didn’t speak in a more moderate tone when he wrote his memoir in the 1990’s; why he didn’t pretend a more universal concern for human rights in order to protect his reputation as a champion of human rights. I say he would not because he will never detract in any way from the utter righteousness of the installation of a Jewish state in Palestine. That can never be questioned, human rights be damned. That’s one reason Elie Wiesel is such a hypocrite. Other people’s struggles can be criticized and shown to be inimical to the rights of others, but never the Jew’s.

I find it interesting that Wiesel chooses the words “Young and old, rich and not so rich,” rather than “rich and poor.” There were no poor Jews? Or is it understood that this was a networking of those with means and influence; the poor were really of no help. They are just pawns in the game, used to parlay the idea that they are the ones for whom all this is being done.

My personal circle narrowed. Kalman left for America; Israel Adler was recalled by the Haganah and was now in a training camp …near Marseilles. My friend Nicholas informed me that he planned to abandon his studies [to go and fight.]

Deep down, I had reservations. Military life was not for me. […] what if I died in combat? I hadn’t yet done anything with my life, had written nothing of the visions and obsessions I bore within myself, hadn’t yet shared them with anyone. […] Nevertheless, I decided to heed the call to arms.

Nicholas and I signed up at the recruitment office … [p167-8]

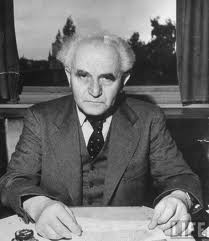

Wiesel says he didn’t pass the medical examination. Really? Were they that particular? The doctor told him he was “not in good shape.” So he continued to work for the Irgun newspaper. Soon it was Friday, May 14, 1948, the day David Ben-Gurion read Israel’s Declaration of Independence over the radio. Wiesel claims to have been extremely moved, possibly beyond anything before in his life. “I was unable to contain my emotion. When had I last wept? It was in an almost painful state of reverence that I greeted Shabbat 10.” [p169]

Left: David Ben-Gurion reads the declaration of “Israel’s” independence, May 14, 1948 in Tel Aviv. A portrait of Theodor Herzl hangs above him. Right: Ben-Gurion, Israel’s first Prime Minister, in the same year.

* * *

The role of the Irgun in Central/Eastern Europe—collaboration with Poland, then Paris

At this point, I would like to insert some information about the role of the Irgun in Central and Eastern Europe from the website http://www.etzel.org.il/english/ac16.htm. It tells of the cooperation between the Polish government and Jewish “resistance” groups before the outbreak of WWII, revealing the desire of European nations, other than Germany, to reduce their Jewish population.

More than three million Jews, concentrated mainly in the large towns, lived in Poland in the 1930s. In Warsaw, for example, Jews constituted one-third of the population. The Polish government, worried by the increase in Jewish influence in the country, not only did nothing to hinder the illegal immigration movement which the Revisionists (Zionist faction of Jabotinsky – Irgun) organized in Poland, but actively assisted it.

In 1936, Jabotinsky met with the Foreign Minister, Josef Beck, and created the infrastructure for collaboration. The Polish government hoped that the establishment of a Jewish state would lead to mass emigration of Jews, thus solving the Jewish problem in Poland.

In 1937, Avraham Stern (Yair), then secretary of the Irgun General Headquarters, arrived in the Polish capital armed with a letter of recommendation from Jabotinsky. He met with senior government officials and laid the practical foundations for cooperation between the Polish army and the Irgun Zvai Le’umi. […] Polish army representatives handed over to Irgun members weapons and ammunition which […] were despatched to Eretz Israel. Some of the weapons were concealed in the false bottoms of crates in which the furniture of prospective immigrants was transported, or in the drums of electrical machines. When the consignments reached Eretz Israel, they were taken to a safe place, and the weapons were removed from their hiding place.

Stern was much helped by Dr. Henryk Strasman, a well known lawyer and an officer in the Polish Reserve force. The Strasmans introduced Stern to the Polish intellectuals and high officials. It was in their home that the preparations for the publication of the Polish periodical “Jerozolima Wyzwolona” (Free Jerusalem) were begun. His wife, Alicia (Lilka) designed the cover – A map of Eretz Israel with the background of an arm holding a gun and the words in Hebrew: ” ” (This Way Only). This became later the symbol of the Irgun. [See poster at top of page]

In March 1939, senior Irgun commanders from Eretz Israel participated in a course held in the Carpathian Mountains, instructed by Polish army officers. The course took place under conditions of great secrecy, and the instructors wore civilian clothing. The participants were not permitted to establish contact with local Jews, and the letters they wrote home were sent to Switzerland, inserted into new envelopes, re-addressed to France, and finally posted from there to Palestine. The trainees received military trainingand were taught tactics of guerilla warfare.

Three remained in Poland: Yaakov Meridor, who was responsible for despatching the weapons received from the Polish army; Shlomo Ben Shlomo, who organized a commanders course for selected members of Irgun cells in Poland, and Zvi Meltzer, who organized a similar course in Lithuania.

September 1, 1939 cut short the extensive activity of the Irgun in Poland and Lithuania. Most of the arms which the Irgun had received were returned to the Polish army and Irgun activity ceased.

After the war, the Irgun General Headquarters decided to renew activity in Europe and to launch a “second front”. The first base was established in Italy, […] As a result of arrests in Italy, Irgun Headquarters in Europe were transferred to Paris. Meanwhile, branches had been set up in various parts of Europe, and attempts were made to strike at British targets. A train transporting British troops was sabotaged, and an explosion occurred in the hotel in Vienna which housed the offices of the British occupation force. However, the blowing up of the British embassy in Rome remained the pinnacle of Irgun operational activity in Europe.

In January 1947, Eliyahu Lankin reached Paris after his successful escape from internment in Africa. Lankin was a member of the Irgun General Headquarters before his arrest and had also served as commander of the Jerusalem district. The French government, which knew of his escape from British custody, gave him an entry visa, and when he reached Paris he was appointed Commander of the Irgun in Europe.

Shmuel Ariel, sent to Paris by the Irgun in early 1946, was in charge of immigration. Ariel established good contacts with the French authorities, and the Haganah called on his services extensively in connection with sailings from France. Thus, for example, Ariel succeeded in negotiating with the French Ministry of Interior the granting of 3,000 entry visas to Jewish refugees arriving in France en route to Palestine. Some 650 of them left aboard the Ben Hecht, 940 on the arms vessel Altalena, and the remainder were transferred to a ship organized by the Haganah. Thanks to Ariel’s close contacts with the French authorities, the Irgun General Headquarters was permitted to operate in Paris without interruption, and to supervise activity in the many branches all over Europe.

While we hear so much about the “Transfer Agreement” and the Zionist collaboration with the German National Socialists under Adolf Hitler, where do we hear that beginning in 1936 the Polish Government was also desirous of, and actively engaged in, transferring their Jews to Palestine? As with the Germans, the breakout of war brought an end to this cooperation. But as soon as the war was over, it started up again in Paris. Paris was then the headquarters of the Irgun in Europe, with the approval of the French Interior Ministry. An Irgun special representative was in charge of illegal immigration to Palestine. Can this explain why Wiesel remained in Paris until 1955? It does shed light on the alternate world of underground Zionist operations that Elie Wiesel was absorbed into … just how deeply we can only speculate.

Next: Part III – Elie Wiesel’s travels and how they were funded.

Endnotes:

5. Wiesel, All Rivers Run to the Sea, p162

6. There is that “I didn’t dare ask” again; better not to know. You’re going to see as we go along that there are several phrases and numbers that Wiesel uses again and again.

7. In the Soviet Union, obviously.

8. A Lithuanian/Russian Jew born to an Orthodox rabbi, and a member of the French Resistance who was arrested in 1942

9. Wiesel is referring to Marion, whom he met and married later. As a “resistance” volunteer herself, she could well have delivered secret documents to his office.

10. Shabbat is the Jewish Sabbath, from sundown Friday to sundown Saturday.

7 Comments

Category Featured | Tags: Tags: All Rivers Run to the Sea, David Ben-Gurion, Elie Farshtei, Francois Wahl, Haganah, Henry Bulawko, Irgun, Shushani/Chouchani, sister Bea, Zion in Kamf,

Social Networks: Facebook, Twitter, Google Bookmarks, del.icio.us, StumbleUpon, Digg, Reddit, Posterous.

Sunday, January 2nd, 2011

By Carolyn Yeager

copyright 2011 carolyn yeager

Is Elie Wiesel just another Mossad asset? The question is not as surprising as it may sound.

The question of how involved Elie Wiesel was with the early terrorist groups that eventually became The Mossad, Israel’s feared intelligence arm, is one that must finally be asked and answered in a straightforward manner. Certainly, Wiesel is no stranger to politics from his young years. Zionism, along with Marxism and Communism, had strong currency among Eastern European Jews during the 20’s and 30’s; it grew only stronger in the atmosphere of the concentration camps and ghettos created by the Hitler regime and its allies during WWII.

By the time the camps were “liberated” and their inmates, along with others who desired to move about and get a new lease on life, streamed into the Allied Displaced Persons [DP] camps in Germany in 1945, the Zionist cause had reached fever-pitch. These camps, in which all Jewish people were treated with most-deserving status—no matter how they behaved or what their actual past had been—were hotbeds of recruitment for Jewish “resistance” groups such as Haganah, Irgun and Lehi, as well as for illegal transportation and entry into Palestine.

Background of Jewish Terrorist Organizations

The first Jewish paramilitary organization, Haganah [“The Defense”], was formed in 1920. It guarded the Jewish settlements that were forming in Palestine from the Arabs, who were beginning to resent the intruders. In 1931, the more militant elements of the Haganah splintered off and formed the Irgun [also called Etzel and “Defense B”], led from 1943-48 by Menachem Begin.

After 1945, the Haganah was a full-fledged terrorist organization, carrying out bombings, sabotage and illegal immigration of Jews into Palestine. Famous members included Rabin, Sharon, Dayan, Zeevi and Dr. Ruth Westheimer. After Israel became a state in 1948, the Haganah became the Israeli Defense Force.

The Irgun policy was based on ultra-radical Ze’ev Jabotinsky’s “Revisionist Zionism,” which declared that every Jew had the right to enter Palestine, and that active retaliation and Jewish armed force were necessary methods to ensure the Jewish state. It was the Irgun that bombed the King David Hotel—killing 91 people and injuring 46—and carried out the infamous Deir Yassin massacre, along with the Lehi [the Stern Gang]. The Irgun is the predecessor to today’s Likud Party.

![EW_Stern [gang]](https://www.eliewieseltattoo.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/01/EW_Stern-gang1.jpg)

(L)Avraham Tehomi, the first Commander of the Irgun; (C) Ze’ev Jabotinsky, Irgun ideologist; (R) Avraham (Yair) Stern, founder of The Stern Gang

A commander in the Irgun, Avraham Stern, defected from the Irgun and founded the Lehi group, also known as the Stern Gang, They were even more fanatical than Irgun, and declared total war against imperialism and the British Empire, even while the British were at war with the Germans.

After May 14, 1948 [Israel’s independence], Irgun representatives in France purchased a ship and weapons, and brought it to the Israeli coast in violation of a ceasefire agreement with the neighboring Arab states and the United Nations. It was with the Irgun in Paris, France that Elie Wiesel found his first job.

Wiesel in France

Wiesel writes in All Rivers Run to the Sea 1, his memoir, that he and his young fellow “survivors” wanted to go to Palestine right from Buchenwald, but their American liberators couldn’t allow them to do that. They settled for free transportation and lodgings in France, sponsored by a Jewish welfare agency, the OSE, and the government of Charles De Gaulle.

Now, if it turns out to be true that Wiesel was not at Buchenwald, as I believe, then he was not on that particular passenger train trip to France that he describes on page 109 of his memoir All Rivers. There, he gives a strange explanation for why he never received French nationality:

The train stopped at the border, and they had us get off. A police official made a speech, of which I understood not a word. When I saw people raising their hands, I assumed they were volunteering for some task. […] I later found out that the policeman had asked for a show of hands of all those who wished to become French citizens. Since I did not respond, they probably wrote in my file: “Refused French nationality.” The consequence of my blunder was endless harassment and administrative hassles …

This is questionable for several reasons. First, he says prior to the above paragraph that he shared a train compartment with a boy from Sighet who knew a few words in French. But why would any of the boys be expected to know French? They wouldn’t. Second, there were two Jewish American Army Chaplains accompanying them who were supposedly looking out for their welfare. Third, Wiesel says, “They probably wrote in my file.” Didn’t he ask about it? Certainly he would have gotten another chance once he explained his mistake to the welfare authorities, since the point of the whole operation is that the boys from Buchenwald, if they were orphans, were offered to become French Nationals.

This simplistic and nonsensical explanation for why he spent years as a “stateless person” is just not convincing. It does not fit the world as we know it. This will be repeated in following explanations he gives for his experiences.

Wiesel writes that they were greeted by the OSE, the children’s rescue society, with all good things: a splendid chateau, lavish meals, smiles and promises. His smaller “group of young believers” requested kosher food and received it. They were also provided with their requested bibles, prayer books and Talmudic tractates, and a study/prayer room.2 Wiesel appears not to be interested in assimilating as a Frenchman, even though he finds his eldest sister to be living nearby. Among this group of youths were Zionists and Bundists. Elie was the former, while the Bundists preferred to “rebuild a Jewish cultural life in the Diaspora.”

Wiesel says he “rededicated” himself to his sacred studies, and in between played chess. One day:

…a couple of strangers wanted to take pictures as we played. One of them asked some questions in bad German; I answered in good Yiddish. Someone said they were journalists, but I had never met a journalist before; they were of no interest to me, and I didn’t see why I should interest them.3

This became the published photograph that is said to have alerted his sister Hilda, who had married an Algerian Jew and was living in Paris, to his whereabouts. In a few days, she had contacted the OSE and the brother-sister reuniting was arranged. But why have we never seen this picture? Why has it disappeared and why does no one of the holocaust historians or Wiesel biographers care enough to search for it? We can reasonably expect that sister Hilda would have kept that magazine picture as a treasured memento, but once again we are confronted with the unexplainable. 4

It was many months later that he reunited with his second sister, Bea, who was in a DP camp in Germany, waiting on a visa to the U.S. or Canada. According to All Rivers, Bea had traveled to Sighet, where Elie had refused to return. There, someone she met told her that her brother was alive. No further details on this—how and why she went to Sighet, and why the folks there would know. At this point in the memoir, Wiesel writes some very sentimental passages that take our attention away from his sisters’ discovery of his whereabouts, and never gets back to it.5

Early connections with Jewish Resistance

The next item of interest to our topic comes on page 120 of All Rivers. In 1947 the OSE arranges for a young Jewish teacher, François Wahl 6, to give Wiesel private French lessons, since he has decided to remain in France for the time being, rather than to emigrate to Palestine [illegally] or to the Americas or Australia. Wiesel writes that, while only two years his senior, Wahl seemed much older, and that “the bond between them was deep and true.” He then informs us that “in 1947, as the underground war raged in Palestine, François performed important secret tasks for a Jewish resistance group.”

During this time, Wiesel’s stated pursuits had solely to do with Jewish religion and politics. Actually, that has never changed, in spite of the effort to make it appear that he was, for a time, a real student at the Sorbonne [see here]. He associated only with other Jews, all of whom were naturally interested in the events in Palestine, by staying within the Jewish welfare system even though he was transferred twice—first to Taverny, then to Versailles. At the latter, he was not only with his Buchenwald group but with other Jewish orphans who had given themselves false identities and/or had lived with Christian families during the war.7

When Wiesel’s best friend Kalman left for Palestine [illegally], Wiesel stayed behind and kept up his love affair with Jerusalem from afar. There can be no doubt that he was familiar and highly sympathetic with the Zionist ideas of forcing their way into Palestine, and had no qualms about their methods.

On page 150 he confides: “I had wanted to write ever since childhood. In Sighet I often went to the offices of the Jewish community to write a page of Bible commentary on the only available Hebrew typewriter.” [See my questions about Wiesel’s typing ability here.] On the same page, Wiesel questions the value of writing, and more particularly, of words themselves.

… I told myself I should write. But I had to be patient. Someday, in years to come, I would celebrate memory, but not yet. Even then I was aware of the deficiencies and inadequacies of language. Words frightened me. What exactly did it mean to speak? Was it a divine or diabolical act? The spoken word and the written word do not reflect the same experience. The mysticism with which my adolescence was imbued made me suspicious of writing.

And on and on. This is a person caught in such a narrow perspective of life based on readings of Judaic mysticism that he has difficulty seeing anything just for what it is. Also, someone who forever contradicts himself. He wants to write but is frightened of words; he loves and hates at the same time.

At the “end of summer” the counselor finally persuades Elie to leave the comfort of Versailles and take a room of his own near the counselor’s home—he was nineteen and one of the last of his group to leave. From here, he continued seeing his mentor Shushani, his French teacher François, and followed Jewish current events closely. He says he bought the newspapers regardless of the expense.

Finally, the momentous event of the U.N. resolution of Nov. 29, 1947, partitioning Palestine to create a homeland for the Jews, excited Wiesel into action. He found the Paris office of the Irgun newspaper, Zion in Kamf, and offered his services. He was accepted. This is what he writes.8 Whether this is the way it really happened we can’t be sure, knowing as we do how Elie Wiesel throughout his life has played fast and loose with the facts.

Next: Part Two – The activities of the Irgun dominate Wiesel’s life in 1948

Endnotes:

- Elie Wiesel, All Rivers Run to the Sea, Alfred A. Knopf, 1995, 432 pgs.

- Ibid, p 110

- Ibid, p 113

- Hilda DID keep it and showed it at the end of her Shoah Foundation “visual history” interview. I wrote about it and posted the picture here.

- Ibid, p 115

- Warren Routledge writes that Wiesel’s biographer Jack Kolbert changed Francois Wahl’s first name to Gustave, probably because Francois Wahl became well known as a homosexual “since he was 15 years old.”

- Ibid, p 130

- Ibid, p.157

5 Comments

Category Featured | Tags: Tags: All Rivers Run to the Sea, Francois Wahl, Haganah, Irgun, Jewish orphans, Mossad, Oeuvre de Secours, Shushani/Chouchani, sister Bea, sister Hilda, Stern gang, Yiddish typewriter, Ze’ev Jabotinsky, Zion in Kamf,

Social Networks: Facebook, Twitter, Google Bookmarks, del.icio.us, StumbleUpon, Digg, Reddit, Posterous.

Friday, August 20th, 2010

By Carolyn Yeager

copyright 2010 Carolyn Yeager

Part Two: Can the books Night and And the World Remained Silent have been written by the same author? What one critic reveals.

We know a lot about the man who calls himself Elie Wiesel from his own mouth and pen, but we know of the Lazar Wiesel born on Sept. 4, 1913 only through Miklos Grüner’s testimony, and of the author of Un di Velt Hot Gesvign (And the World Remained Silent) through the work itself. So let’s consider what we know of these two men before we look at their books.

The city of Sighet can be seen in the purple-colored Maramures district on this map of Greater Romania in the 1930’s.

Who is Elie Wiesel?

Elie Wiesel says in Night that he grew up in a “little town in Translyvania,” and his father was a well-known, respected figure within the Hasidic Orthodox Jewish community. However, Sanford Sternlicht tells us that Maramurossziget, Romania had a population of ninety thousand people, of whom over one-third were Jewish.15 Some say it was almost half. Sternlicht also writes that in April 1944, fifteen thousand Jews from Sighet and eighteen thousand more from outlying villages were deported. How many with the name of Wiesel might have been among that large group? I counted 19 Eliezer or Lazar Wiesel’s or Visel’s from the Maramures District of Romania listed as Shoah Victims on the Yad Vashem Central Database. Just think—according to their friends and relatives, nineteen men of the same name from this district perished in the camps in that one year. It causes one to wonder how many Lazar and Eliezer Wiesels didn’t perish, but became survivors and went on to write books, perhaps.

Lazare, Lazar, and Eliezer are the same name. Another variation is Leizer (prounounced Loizer). A pet version of the name is Liczu; a shortened version is Elie.16 In spite of having a popular, oft-used name, Elie Wiesel describes a unique picture of his life. The common language of the Orthodox Hasidic Jews of Sighet was Yiddish. Wiesel has said he thinks in Yiddish, but speaks and writes in French.17

In his memoir, he admits that he was a difficult, complaining child—a weak child who didn’t eat enough and liked to stay in bed.18 He comes across as definitely spoiled, the only son among three daughters.

According to Gary Henry, as well as other of Wiesel’s biographers and Wiesel himself, young Elie Wiesel was exceptionally fervent about the Hasidic way of life. He studied Torah, Talmud and Kabbalah; prayed and fasted and longed to penetrate the secrets of Jewish mysticism to such an extreme that he had “little time for the usual joys of childhood and became chronically weak and sickly from his habitual fasting.”19 His parents had to insist he combine secular studies with his Talmudic and Kabbalistic devotion. Wiesel says in Night that he ran to the synagogue every evening to pray and “weep” and met with a local Kabbalist teacher daily (Moishe the Beadle), in spite of his father’s disapproved on the grounds Elie was too young for such knowledge.

Of his elementary school studies, Wiesel writes: “[My teachers] were kind enough to look the other way when I was absent, which was often, since I was less concerned with secular studies than with holy books.” 20 And “in high school I continued to learn, only to forget.”

But his plans to become a pious, learned Jew came to an end with the deportation of Hungary’s Jews to Auschwitz-Birkenau. Wiesel has told this story both in his first book Night and in his memoir All Rivers Run to the Sea, and in many talks and lectures.

After liberation, in France, Wiesel met a Jewish scholar and master of the Talmud who gave his name simply as Shushani or Chouchani.21,22 In his memoir, Wiesel wrote:

It was in 1947 that Shushani, the mysterious Talmudic scholar, reappeared in my life. For two or three years he taught me unforgettable lessons about the limits of language and reason, about the behavior of sages and madmen, about the obscure paths of thought as it wends its way across centuries and cultures.23

Wiesel describes this person as “dirty,” “hairy,” and “ugly,” a “vagabond” who accosted him in 1947 when he was 18, and then became his mentor and one of his most influential teachers. Reportedly, when Chouchani died in 1968, Wiesel paid for his gravestone located in Montevideo, Uruguay, on which he had inscribed: “The wise Rabbi Chouchani of blessed memory. His birth and his life are sealed in enigma.” According to Wikipedia, Chouchani taught in Paris between the years of 1947 and 1952. He disappeared for a while after that, evidently spent some time in the newly-formed state of Israel, returned to Paris briefly, and then left for South America where he lived until his death.24

This could be important because it links up with Wiesel’s visits to Israel and his trip to Brazil in 1954. While the common narrative of Elie Wiesel’s post-liberation years focuses on his being a student at the Sorbonne University, Paris and an aspiring journalist, these sources reveal that he was still deeply into Jewish mysticism and involved with the Israeli resistance movement in Palestine.

Wiesel received a $16-a week-stipend from the welfare agencies.25 In addition, he worked as a translator for the militant Yiddish weekly Zion in Kamf. In 1948, at the age of 19, he went to Israel as a war correspondent for the French-Jewish newspaper L’arche, where he eventually became a correspondent for the Tel Aviv newspaper Yedioth Ahronoth.26 Shira Schoenberg at the Jewish Virtual Library puts it this way: “he became involved with the Irgun, a Jewish militant (terrorist) organization in Palestine, and translated materials from Hebrew to Yiddish for the Irgun’s newspaper […] in the 1950s he traveled around the world as a reporter.”27

The above paints a picture of a religiously-inclined personality, strongly drawn to, perhaps even obsessed with, the most mystical teachings and “secrets” of his Judaic tribe. By the age of 15, this trait was well-established. One year in detention of whatever kind (yet to be established for certain), hiding out, or other privations had no power to change these strong interests, which asserted themselves again immediately upon his “release.”

What kind of personality was Lazar Wiesel?

We only know of the Lazar Wiesel who was born on Sept. 4, 1913 through Miklos Grüner , and of the author of Un di Velt Hot Gesvign through the work itself. Note that I’m not claiming these two are one and the same.

Grüner writes in Stolen Identity28 that after the death of his father in Birkenau “after six months,” which must have been in October or early November 1944, he

went to see the friends of my father and brother, Abraham Wiesel and his brother Lazar Wiesel from Maramorossziget, [ …] Abraham was born in 1900 and his tattooed number was A-7712 and Lazar was born in 1913 and was tattooed as A-7713, whereas my father had A-11102, my brother A-11103, and I who stood after my brother finished up with the number A-11104. When they had heard the story of my father, they promised to take care of me and from then on, they became my protectors and brothers and an additional refuge …” (p. 24)

[…]

About three months had passed by, in my stage of hopelessness, I was informed by my “brothers” (Abraham and Lazar) that the Russians had managed to break through and they were on their way to liberate us from “BUNA,” Auschwitz III. (p. 25)

[…]

During the long march […] the walking became difficult and it was also hard to keep up with Abraham and Lazar. That was until I reached a place 30 km from Monowitz “Buna” called Mikolow, with a huge brickyard. Tired as I was after walking under the heavy winter conditions, I fell asleep on a pallet […] When night turned to dawn, I took my time and made my attempt to find Abraham and Lazar […] Later on I managed to find them and for the next 30 kilometres I had no problem in keeping up with them […] up to the next labor camp in Gliwice. After about three days stay in Gliwice, we were ordered to climb up onto an open railway carriage, without any given destination. […] Once again I lost Lazar and Abraham, but […] I found my old friend Karl … (p. 26)

The journey lasted about four days. On our arrival … I wobbled away to search for Abraham and Lazar. After a while, I found Lazar who told me that Abraham was having a hard time of it and he was not sure that Abraham would be able to pull through. He also mentioned that no matter what, he was going to stay with Abraham and was asking for God’s blessing. (p. 27)

[…]

When finally we were given our clothes (after showers, etc), we were registered and received new numbers that we had to memorize like children, and then we were assigned to Barrack 66. (Comment: “we” does not include Lazar and Abraham. Barrack 66 was the children’s barracks in the “small camp” at Buchenwald. Grüner was 16 yrs. old and his father had died.)

About a week later, I couldn’t believe my own eyes to see Lazar in our Block 66. He told me that Abraham had passed away four days after our arrival at Buchenwald. He made it clear that he had received special permission to join us children in Block 66, since he was so much older than us.

Five days before the liberation in April […] In our Block 66, attempts were made to get us to the main gate. The supervisor of our block, called Gustav with his red hair, indeed had managed to drive us out of the block and was determined to drive us to the gate. When we reached the middle of the yard, I pulled my trousers down (halfway), then ran off to the side and kept on running as fast as I could to the nearest block, which I believe was Block 57. I asked the man in the lower bunk if the place next to him was occupied, and I simultaneously took my position in the left hand corner of the bunk, where I remained until I was liberated.

If my memory serves me correctly, on the fourth day after my liberation, AMERICAN SOLDIERS came into the block and a picture was taken of us survivors of the Holocaust. […] This picture has become famous all over the world as a memory of the Holocaust.29 After a change of clothing and a medical examination, I went to look for Lazar, but unfortunately I could not find him anywhere. (p 28)

On page 30, Grüner writes: “When the liberating American soldiers came into our barrack, they discovered a block full of emaciated people lying in bunks. In the next minute a flashlight from a camera went off, and I without my knowing, was caught on the picture forever.”

Grüner never saw Lazar Wiesel again, since, according to him, Lazar was sent to France, and Grüner to a sanatorium in Switzerland. When Grüner was contacted in 1986 about meeting the Nobel Prize winner Elie Wiesel, he thought he was going to be meeting his old friend Lazar Wiesel.

What does Un di Velt Hot Gesvign tell us about Eliezer Wiesel?

Naomi Siedman, Professor of Jewish Culture at Graduate Theological Union, is one of the few academics to delve into Wiesel’s early writings with a critical spirit. Her very controversial essay “Elie Wiesel and the Scandal of Jewish Rage,”30 written in 1996, one year after the publication of Wiesel’s memoir All Rivers Run to the Sea, examines several passages in Night and compares them to passages in the Yiddish original. Among the relevant issues she brings up is this one:

Let me be clear: the interpretation of the Holocaust as a religious theological event is not a tendentious imposition on Night but rather a careful reading of the work.

In other words, Night presents the Holocaust as a religious event, rather than historical. In contrast, Siedman found that the Yiddish version, Un di Velt, published two years prior to the publication of Night, was similar to all others in the “growing genre of Yiddish Holocaust memoirs” which were praised for their “comprehensiveness, the thoroughness of (their) documentation not only of the genocide but also, of its victims.” Un di Velt Hot Gesvign was published as volume 117 of Mark Turkov’s Dos poylishe yidntum (Polish Jewry) in Buenos Aires.

Siedman refers to a reviewer of the mostly Polish Yiddish series when she writes:

For the Yiddish reader, Eliezer (as he is called here) Wiesel’s memoir was one among many, valuable for its contributing an account of what was certainly an unusual circumstance among East European Jews: their ignorance, as late as the spring of 1944, of the scale and nature of the Germans’ genocidal intentions. The experiences of the Jews of Transylvania may have been illuminating, but certainly none among the readers of Turkov’s series on Polish Jewry would have taken it as representative. As the review makes clear, the value of survivor testimony was in its specificity and comprehensiveness; Turkov’s series was not alone in its preference. Yiddish Holocaust memoirs often modeled themselves on the local chronical (pinkes ) or memorial book (yizker-bukh ) in which catalogs of names, addresses, and occupations served as form and motivation. It is within this literary context, against this set of generic conventions, that Wiesel published the first of his Holocaust memoirs.

Siedman continues that “Un di velt has been variously referred to as the original Yiddish version of Night and described as more than four times as long; actually, it is 245 pages to the French 158 pages.” But the “four times as long” was referring to the original 862 pages that Turkov cut down to 245. Siedman reminds us that Wiesel had earlier described his writing of the Yiddish with no revisions, “frantically scribbled, without reading.” She says this, and Wiesel’s complaint that the original manuscript was never returned to him, are “confusing and possibly contradictory.” She then writes:

What distinguishes the Yiddish from the French is not so much length as attention to detail, an adherence to that principle of comprehensiveness so valued by the editors and reviewers of the Polish Jewry series. Thus, whereas the first page of Night succinctly and picturesquely describes Sighet as “that little town in Transylvania where I spent my childhood,” Un di velt introduces Sighet as “the most important city [shtot] and the one with the largest Jewish population in the province of Marmarosh.” 31 The Yiddish goes on to provide a historical account of the region: “Until, the First World War, Sighet belonged to Austro-Hungary. Then it became part of Romania. In 1940, Hungary acquired it again.”

The great length of the original was no doubt due to the extensive detail it contained about the events, places and people that were the subject of the narrative. Despite the fact that descriptive detail is not a characteristic in any of Wiesel’s known writing, he would never have been able to write all that detail in two weeks in a ship’s cabin, relying only on his memory. He even says he saw no one during that time and cut himself off from everything. In the writing style of Elie Wiesel that we’re familiar with, what could he possibly have said to fill up 862 pages? Impossible!

Another point made by Siedman: And while the French memoir is dedicated “in memory of my parents and of my little sister, Tsipora,” the Yiddish (book) names both victims and perpetrators: “This book is dedicated to the eternal memory of my mother Sarah, father Shlomo, and my little sister Tsipora — who were killed by the German murderers.” 32 The Yiddish dedication is an accusation from a very angry Jew who is assigning exact blame for who was responsible. In addition, this brings to mind the fact that Elie Wiesel’s youngest sister was named Judith at birth, not Tsipora (according to his sister Hilda’s testimony).

Siedman says the effect of this editing from the Yiddish to the French was:

…to position the memoir within a different literary genre. Even the title Un di velt hot geshvign signifies a kind of silence very distant from the mystical silence at the heart of Night. The Yiddish title (And the World Remained Silent) indicts the world that did nothing to stop the Holocaust and allows its perpetrators to carry on normal lives […] From the historical and political specificities of Yiddish documentary testimony, Wiesel and his French publishing house fashioned something closer to mythopoetic narrative.

Myth and poetry … from a very historical and political original testimony. Wiesel attempted to explain this in his memoir by describing his French publisher’s objections to his documentary approach: “Lindon was unhappy with my probably too abstract manner of introducing the subject. Nor was he enamored of two pages (only two pages?) which sought to describe the premises and early phases of the tragedy. Testimony from survivors tends to begin with these sorts of descriptions, evoking loved ones as well as one’s hometown before the annihilation, as if breathing life into them one last time.” 33 Just how convincing that is I leave up to the reader.

The most controversial part of Siedman’s essay is about the Jewish commandment for revenge against one’s enemies. The author of the Yiddish writes that right after the liberation at Buchenwald:

Early the next day Jewish boys ran off to Weimar to steal clothing and potatoes. And to rape German girls [un tsu fargvaldikn daytshe shikses]. The historical commandment of revenge was not fulfilled.” 34

This reflects the same angry, stern Jew who demands the Jewish law of revenge upon one’s enemies be followed. He does not consider “raping German girls” to be sufficient revenge; thus he says the historical commandment was not fulfilled. In the French and English, it was softened to: “On the following morning, some of the young men went to Weimar to get some potatoes and clothes—and to sleep with girls. But of revenge, not a sign.”35 Siedman comments on this passage:

To describe the differences between these versions as a stylistic reworking is to miss the extent of what is suppressed in the French. Un di velt depicts a post-Holocaust landscape in which Jewish boys “run off” to steal provisions and rape German girls; Night extracts from this scene of lawless retribution a far more innocent picture of the aftermath of the war, with young men going off to the nearest city to look for clothes and sex. In the Yiddish, the survivors are explicitly described as Jews and their victims (or intended victims) as German; in the French, they are just young men and women. The narrator of both versions decries the Jewish failure to take revenge against the Germans, but this failure means something different when it is emblematized, as it is in Yiddish, with the rape of German women. The implication, in the Yiddish, is that rape is a frivolous dereliction of the obligation to fulfill the “historical commandment of revenge”; presumably fulfillment of this obligation would involve a concerted and public act of retribution with a clearly defined target. Un di velt does not spell out what form this retribution might take, only that it is sanctioned — even commanded — by Jewish history and tradition.

The final passage that Siedman compares is the famous ending of Night. The Yiddish version presents not only a longer narrative, but a radically different person who emerges from his camp experience at the time of liberation.

Three days after liberation I became very ill; food-poisoning. They took me to the hospital and the doctors said that I was gone. For two weeks I lay in the hospital between life and death. My situation grew worse from day to day.

One fine day I got up—with the last of my energy—and went over to the mirror that was hanging on the wall. I wanted to see myself. I had not seen myself since the ghetto. From the mirror a skeleton gazed out. Skin and bones. I saw the image of myself after my death. It was at that instant that the will to live was awakened. Without knowing why, I raised a balled-up fist and smashed the mirror, breaking the image that lived within it. And then — I fainted… From that moment on my health began to improve. I stayed in bed for a few more days, in the course of which I wrote the outline of the book you are holding in your hand, dear reader.

But—Now, ten years after Buchenwald, I see that the world is forgetting. Germany is a sovereign state, the German army has been reborn. The bestial sadist of Buchenwald, Ilsa Koch, is happily raising her children. War criminals stroll in the streets of Hamburg and Munich. The past has been erased. Forgotten. Germans and anti-Semites persuade the world that the story of the six million Jewish martyrs is a fantasy, and the naive world will probably believe them, if not today, then tomorrow or the next day.

So I thought it would be a good idea to publish a book based on the notes I wrote in Buchenwald. I am not so naive to believe that this book will change history or shake people’s beliefs. Books no longer have the power they once had. Those who were silent yesterday will also be silent tomorrow. I often ask myself, now, ten years after Buchenwald : Was it worth breaking that mirror? Was it worth it? 36

This entire passage sounds nothing like Elie Wiesel, or anything he has written. It is matter of fact, not indulging in self-pity but addressing the reality of the situation with a cynical eye. The author is concerned with the traditional problems of Jews, as he sees it, and their welfare. His “witness” as a survivor is not mystical or universalized, but is about assessing blame. His depiction of smashing the mirror that holds his dead-looking image, and how that expression of powerful anger and life-affirmation revived him, is convincing. Right away, he wants to write about his experience, and he begins. Anger and “putting it all down” is the way out of depression and listlessness.

Yet the author and editors of Night have removed almost all of this and end very differently:

One day I was able to get up, after gathering all my strength. I wanted to see myself in the mirror hanging from the opposite wall. I had not seen myself since the ghetto.

From the depths of the mirror, a corpse gazed back at me.

The look in his eyes, as they stared into mine, has never left me.37

No anger. No recuperation or recovery possible for this character. No closure. Elie Wiesel leaves us in Night with the image of death, and for the rest of his life he will pour it out on the world through his writings. This is his legacy; the Holocaust never ends.

Siedman comments on these two endings:

There are two survivors, then, a Yiddish and a French—or perhaps we should say one survivor who speaks to a Jewish audience and one whose first reader is a French Catholic. The survivor who met with Mauriac labors under the self-imposed seal and burden of silence, the silence of his association with the dead. The Yiddish survivor is alive with a vengeance and eager to break the wall of indifference he feels surrounds him.

Naomi Siedman intends the “two survivors” to be taken symbolically, as she is a “respected” Jewish academic who does not question the Holocaust story, and does not question (publicly at least) the authenticity of Elie Wiesel as the author of the Yiddish 862-page And the World Remained Silent, no matter what difficulties are encountered. As she continues in this essay, she posits Francois Mauriac’s powerful influence on Elie Wiesel as the way of explaining the further shortening and redirection of the focus of the original text. This is not my position, so I don’t find it profitable to seek for the origins of Night in Mauriac’s Catholic/Christian views. I believe there are sufficient grounds to consider a different authorship for Un di Velt Hot Gesvign, and that neutral-minded, critical thinkers who have an interest in this subject would not object to studying it from this angle.

However the grounds for doing so have not been exhausted by these two essays, so I will continue with a summing up in Part Three.

Endnotes:

15) Sanford Sternlicht, Student Companion to Elie Wiesel, Greenwood Press, Westport, CT, 2003, p. 3.

16) Ibid.

17) First Person: Life & Work. http://www.pbs.org/eliewiesel/life/index.html

18) All Rivers Run to the Sea, p. 9

19) First Person: http://www.pbs.org/eliewiesel/life/henry.html

20) Rivers, p. 20

21) http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/biography/Wiesel.html

22) http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Monsieur_Chouchani

23) Rivers, p. 121

24) Wikipedia, Chouchani

25) http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Night_(book) Miklos Grüner says his 32-year-old friend Lazar Wiesel was given an apartment and an income because he had travelled with the orphans to France, under special permission. (see Stolen Identity by Grüner, printed in Sweden, 2007)

26) Wiki/Night

27) Jewish virtual library, ibid.

28) http://www.scribd.com/doc/33182028/STOLEN-IDENTITY-Elie-Wiesel

29) Grüner is speaking of Block 56, where what was to become the “famous Buchenwald liberation photograph” was taken by an American military photographer on April 16, 1945, five days after liberation. See our analysis of this photo under “The Evidence” on the menu bar.

30) “Elie Wiesel and the Scandal of Jewish Rage,” Seidman, ibid.

31) Eliezer Vizel, Un di velt hot geshvign (Buenos Aires, 1956), p. 7

32) Un di velt, n.p.

33) Rivers, p. 319

34) Un di velt, 244.

35) Night, 120.

36) Un di velt, 244-45

37) Night, 120.

11 Comments

Category Featured | Tags: Tags: Hasidic Jews, Miklos Grüner, Naomi Siedman, Night, Romania, Shushani/Chouchani, Sighet, Un di Velt Hot Gesvign, Zion in Kamf,

Social Networks: Facebook, Twitter, Google Bookmarks, del.icio.us, StumbleUpon, Digg, Reddit, Posterous.

![EW_Stern [gang]](https://www.eliewieseltattoo.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/01/EW_Stern-gang1.jpg)