Archive for May, 2016

Sunday, May 22nd, 2016

Joshua Kaufman poses with his daughters Alexandra (left) and Rachel in front of the Chabad building in Berlin, after leaving the show-trial in Detmold. (photo from Jewish Journal)

By Carolyn Yeager

That’s not asking too much. He burst on the scene (with the help of Bild news organization) of what is already a show-trial in Detmold, Germany and made it even showier. He sought attention for himself.

He is quoted by NBC News as proclaiming in the courtroom, referring to Auschwitz

“Can you imagine working in a crematorium, when you are only 15 years old? I had to break the bones of the dead to get them untangled … I am not Joshua Kaufman, I am number 109023.”

[Note: It has been discovered, on 7-5-16, that the number Kaufman gave to NBC when speaking about Auschwitz was his Dachau prisoner number. Keep that in mind as you read this article.]

I think, under the circumstances, this statement requires him to tell us if he has this number tattooed on his arm. He sought publicity for his story of being a victim of Auschwitz – no one dragged him into that courtroom as they dragged Reinhold Hanning, the defendant. He can’t selectively say what he wants and hold back what he doesn’t want to say. Plus most of his fellow Auschwitz deportees willingly show their tattoo – those that have one, that is.

I have explained elsewhere that according to the bits and pieces Joshua Kaufman has thrown out there (not in any chronological order, by the way), he cannot have had the Auschwitz number 109023. According to the Auschwitz-Birkenau Museum web site, as a Hungarian Jew arriving at Birkenau in 1944, his number would have been preceded by an ‘A’ followed by a number no higher than 20,000. The number he gives is over 100,000. Because of this discrepancy, which he himself originated, he is responsible for answering how he came up with this number.

A second problem with this statement is that it can be shown he was 16 years old when he would have been in Auschwitz in 1944. Yet he even says he was 15 at Dachau, in 1945. It appears he has chosen the age of 15 for his victim story because it has a better ring to it than does sixteen.

A Media Creation

The media won’t ask such a question or bring up any discrepancies. The Joshua Kaufman story is a media creation. Beginning with the Daily Mail UK‘s trumped-up January 2015 story about a reunion with his American “liberator,” then moving on to Germany’s Bild and it’s before-and-after arrival video, plus the US’s NBC News coverage in the courtroom with Kaufman, it is media creating the news. Yet with these three major news outlets covering the man’s story, we still know practically nothing of substance about Kaufman. All they give us are a few outrageous lies (like the one quoted above), and ‘human interest’ profiles.

A Bild photographer took this picture of Kaufman’s home and work van when a team visited him in California before he even left for Germany to crash the show-trial of Reinhold Hanning. Note Kaufman walking toward his front door.

Here are some things I’ve learned about him from carefully scanning the news articles:

1. He comes from Hungary, born in 1928.

2. He was a “survivor” of the Debrecen ghetto.

3. He was deported to Auschwitz (probably in 1944), then worked in 3 smaller camps, ending the war in Dachau where he was liberated on April 30, 1945.

4. He moved to Israel at an unknown date after the war, stayed there for 25 years (some sources say 30 years) and served in the IDF during two wars in 1967 and 1973, then moved to the United States before 1975.

5. He married at age 47, which would have been in 1975, and had a family of four daughters.

6. He worked as an independent plumber in California.

7. He never talked about his holocaust experience until recently because [he said] he felt guilty about throwing fellow Jews into cement mixers. He’s talking about it now because he says, “In ten years’ time, there will probably be no one left who survived it.”

So let’s start with number one and two:

In this cropped photo from the Daily Mail picture layout in January 2015, we can see Kaufman is wearing the exact same clothes he wore in May 2016 at the trial in Detmold, and in Berlin, above.

Kaufman says he is 88 years old in May 2016 which gives him a birth date of 1928. It was his “liberator” Daniel Gillespie (in photo at left) who identified Kaufman to the Daily Mail as a Hungarian Jew. Bild reinforces that by writing that he was a survivor of the Debrecen ghetto:

Kaufman survived the Debrecen ghetto (Hungary). He also survived the Auschwitz and Dachau concentration camps. In Dachau, he was freed on 30 April 1945. Following his liberation, he lived in Israel for 25 years. Kaufman: “In the concentration camp, I was no longer a human being, but an animal. Aged 15, I had to carry 50-kilo bags of cement for more than 12 hours a day. Everyone who could not manage that was thrown into the cement mixer.

Does anyone at Bild really think that exhausted workers were thrown into the cement mixer? I doubt it, but not a questioning word is heard. Checking out the Debrecen ghetto, I found this on Wikipedia:

The order to erect a ghetto there was issued on April 28, 1944. They finished building the ghetto walls on May 15. On June 14 all Debrecen Jews were deported to the nearby Serly brickyards. Most of the Debrecen Jews were deported to Auschwitz, arriving there on July 3, 1944.

The Debrecen ghetto was only used for one month before they were deported to Auschwitz. Kaufman, being among them, wouldn’t have arrived until July 3, 1944, and spent only 10 months at various camps. Or, he never left Hungary at all.

Debrecen was liberated by the Soviet Army on 20 October 1944. Some 4,000 Jews of Debrecen and its surroundings survived the war, creating a community of 4,640 in 1946 – the largest in the region. About 400 of those moved to Israel, and many others moved to the west by 1970.

Considering he doesn’t say when he was arrested, or what he did immediately after liberation from Dachau, he could very well be one of the 400 who moved to Israel from Debrecen and then to the United States in the 1970’s. But, in any case, his alleged Auschwitz number doesn’t fit his history, as far as we can know it. More on that in a moment. First I want to include some history of Debrecen, Hungary’s second largest city, from Wikipedia:

Jews were first allowed to settle in Debrecen in 1814, with an initial population count of 118 men within 4 years. Twenty years later, they were allowed to purchase land and homes. By 1919, they consisted 10% of the population (with over 10,000 community members listed) and owned almost half of the large properties in and around the town

In 100 years they went from 0 to 10% of the population, from 118 to 10,000, and owned 50% of the large properties. This is why they were and are resented. The mistake came when they were given the same rights as Hungarians by being allowed to purchase land and homes anywhere. If individual Jews are not wealthy themselves, they get money from Jews who are wealthy, even abroad, and buy up everything they can as their agent. So the Hungarians were glad to get rid of these Jews when they were deported — not to a death camp but to a labor or detention camp.

At that time, in 1944, Kaufman was 16 years old. He has shown pictures of himself in the Bild video in which he appears to be a well-to-do Jew, both before and after his “ordeal.”

More on Kaufman’s history

Lookee here. Now-”famous-holocaust-survivor” Joshua Kaufman attends the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum 2015 Los Angeles Dinner at The Beverly Hilton Hotel on March 16, 2015 in Beverly Hills, California. The big layout in the Daily Mail appeared only two months earlier in January 2015. He became a star.

Of numbers 3 through 6, I have no further information than what is stated.

Number 7 tells us that Kaufman’s objective is to help the Jewish case for “The Holocaust,” just like Martin Gray, Elie Wiesel and Paul Argiewicz, and hundreds of others. It’s not about reality but about what’s good for the Jews. Kaufman jumps right into it.

“I lost 100 members of my family, At age 15, I was working in a gas chamber in Auschwitz, dragging out bodies.”

If he became a “sondercommando” working in a gas chamber, he would certainly have been tattooed. Bild newspaper was even told that he had to transport the dead bodies out of the gas chamber with a wheelbarrow. “In Auschwitz, Kaufman had to transport the dead bodies out of the gas chamber with a wheelbarrow. He will talk about this during the trial,” they wrote. A wheelbarrow!? Excuse me, but I have to laugh at that. With 20,000 allegedly gassed per day at that time, you would need a hundred people like him, all bumping into each other with their wheelbarrows!

Then this man Kaufman, who does not answer questions himself, has the gall to make demands on defendant Hanning:

“I would like to hear answers from him. How can you act this inhumanely? How can you live with it? How was he able to happily go home to his family in the evenings? I want him to beg for forgiveness.”

Who is this guy lecturing Germans – showing up at an on-going trial, whether it be right or wrong (it’s wrong, but he’s not trying to right it), with his highly questionable story? What a completely arrogant human being. He goes on:

“They should know what happened to us. In ten years’ time, there will probably be no one left who survived it. That’s why I am talking about it now. For a long time, I did not [talk about it] because I did not feel like a hero. I felt guilty. After all, I had to throw people into the cement mixer, too. Not a single minute passes without my having to think of Auschwitz. I will speak for everyone who did not survive.” (Except it was at Dachau where he says he threw people into the cement mixer.)

He was not a hero! He now thinks people see him that way, after all the movies and books and endless newspaper stories he’s seen over the past 50 years. In the Bild video, he gives himself away by anticipating disbelief in advance, saying: “Everything I did – and nothing is copied from a book and nothing from a movie – everything myself experienced.” That means it’s just the opposite. It was all copied because he only mentions extreme things that never took place in reality. His goal is to exemplify the “Nazis” as evil personified and himself as an innocent survivor of that evil, but what he chooses to say portrays him as just the opposite. As a villain. He “broke the bones” of dead Jews and threw others in a cement mixer!

He volunteered for the ‘gas chamber’ work at Auschwitz

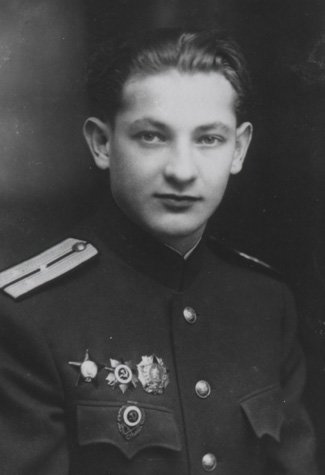

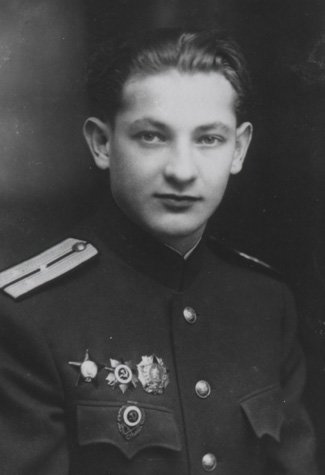

Orit Arfa, a friend of Kaufman’s daughters, wrote a story published in the Jewish Journal of her meeting with the three of them after they left Detmold and came to Berlin. The occasion was a Shabbat (Friday night) dinner at an Orthodox Chabad meeting place. Orit called Joshua “Yehoshua” and said “he had hurt his knee a few weeks earlier but decided he must travel to Germany to seek justice.”

Justice?! For whom? More justice for Jews is all he can mean. She wrote:

He had prepared his words, how he had lugged dead bodies out of Auschwitz gas chambers, pulling them apart as they stuck together during their murder. He was 15 at the time, and volunteering for such gruesome work helped keep him alive.

I get the feeling she read this in the news accounts of the trial, don’t you? Maybe she then asked him about it because she quoted Kaufman as saying:

“It was a way for me to stay alive and to see what was going on around the camp,” Yehoshua related at the Chabad table.

How casually stated! He volunteered to assist in the gassing and cremating of fellow Hungarian Jews in order to stay alive himself! Since he has also said he was sent out to work from Auschwitz, that is not what kept him alive. Big Lie. Another reason was to see what was going on around the camp? Like a tourist? Or a detective? How superficial and unfeeling is this statement. Note he doesn’t say which gas chamber or crematorium he worked in, as if there were only one. Funny no one asked him. But then Orit tells us:

But he seemed more interested in discussing other subjects, like why I wasn’t married. […] He enthused how pleased he was to see me, and how glad they decided to go to Chabad in the end, despite physical and emotional exhaustion from long train rides and legal roller coasters. He looked proudly around the room of Jews singing Shabbat hymns.

So he wants to change the subject, does he? He’s not interested in going into any detail about his stories. This, I think, is the most important sentence I’ve come across, that he didn’t want to discuss it further. He had his “prepared words” and that’s all he had.

After berating Reinhold Hanning for not confessing to what he did not do and did not know, but remaining silent, Joshua Kaufman reveals himself as the most silent of all when it comes to what he doesn’t know and did not do. The Media also remains silent in the face of obvious and important contradictions and impossible claims. Both Kaufman and the Media are engaging in a hypocrisy so entrenched the public barely notices it. But I notice it and I want to know:

How does Kaufman explain his number 109023? Where is his tattoo? I am demanding answers from him. Why don’t you join me.

8 Comments

Category Featured | Tags: Tags: Auschwitz-Birkenau, Bild, Dachau, Daily Mail, Holocaust fraud, Joshua Kaufman, NBC News, Reinhold Hanning,

Social Networks: Facebook, Twitter, Google Bookmarks, del.icio.us, StumbleUpon, Digg, Reddit, Posterous.

Friday, May 13th, 2016

Martin Gray in his old age. Throughout his life as an entrepreneur he wrote a number of books, but his most famous one was written by someone else.

BY CAROLYN YEAGER

When I myself told Gray, the “author”, that he had manifestly never been to, nor escaped from Treblinka, he finally asked, despairingly: “But does it matter?” Wasn’t the only thing that Treblinka did happen, that it be written about, and that some Jews should be shown to have been heroic? -Gitta Sereny, holocaust historian

The French writer Martin Gray, known for his autobiographical book For those I loved, was found dead in the pool of his house in Ciney, Belgium on 25 April 2016 at the age of 93.

So read the newspaper report when his death was announced. But French? Martin Gray was born Mieczysław Grajewski on the 27th of April, 1922 in Warsaw, which made him 17-years old when the Germans and Russians invaded Poland in 1939. Yet in his “autobiographical” book he is only 14 years of age in that year.

September 1939: the month of my real birth. I know almost nothing of the previous fourteen years. [page 3]

Lowering your age is in the tradition of holocaust surliever stories. Elie Wiesel removed a year from his real-life age in his “autobiographical” Night. He took 3 years off his younger sister’s age—she went from ten to seven. Paul Argeiwicz, whom I recently wrote about, reduced his age by five years, from 16 to eleven. It goes in the other direction too. There is a holocaust surlievor in the news recently who claims to be 112 years old. He lives in Israel. I don’t believe for a minute he is that old; he doesn’t look it but gives credit to a “positive attitude.” More likely, he got different papers after the war. There is also a female surlievor who claims she is 97, but looks more like 79. (More pictures here.) They all have some purpose in fiddling with their age – in the case of Grajewski I think it’s first because the younger he is, the more impressive are his amazing accomplishments. But also because he is portrayed as youthfully ignorant of all that preceded September 1939; all he knows is that their peaceful life suddenly ends, destroyed by the invading German neighbor who unaccountably hates them.

The story he tells is like a child’s fairy tale, with clear-cut good and evil figures, victims and perpetrators. The Germans are the bad guys, of course, the Poles are victims who are turned nasty by the Germans, and only the Jews are authentic good guys. The Jews in Poland do what they have to do to survive the evil of others.

In the story, his father is brave, strong, with admirable character.

To me, my father—tall, straight-backed, and so firm of hand—seemed as if he were himself the origin of the world.

His mother is loyal and loving.

We’d come home, my father would open the door. I can still recall the sweet fragrance. My two younger brothers [and] my mother would be there and the table was set for supper.

They owned a glove manufacturing business. They were prosperous, life was good. Then, as if out of the blue, disaster struck. There is no mention of Polish intransigence born of the British and French promise to defend Poland in just such an eventuality. No mention of the secret US diplomatic correspondence urging the Poles not to cooperate with Germany – diplomacy that went on for months while Poland grew increasingly belligerent toward the German proposals. No, this is a story only about the personal bravery of a young Jew… set among the familiar myths of the Polish Resistance and the role of Jews in it.

He peppers his narrative of life in Warsaw after Poland surrendered with the obligatory incidents of German “soldiers” ridiculing Jews for sport, pulling at their beards, shooting them at will — things that did not happen in the disciplined ranks of either the Wehrmacht or of the police. The type of incidents described are solely meant to portray “the ugly Nazi” in contrast to the more civilized Jews, and to evoke as much sympathy as possible for their plight.

Young NKVD Captain Mieczysław Grajewski wearing his Soviet decorations, including the Order of the Red Star.

We don’t hear about the treatment of Poles by the Soviet invaders from the East – like the Katyn massacre and mass burial in pits of many thousands of Polish officers and intellectuals. No, because the Soviets were protective of the Jews while deadly toward the Catholic Poles, and Grajewski and his family were Jewish. Grajewski eventually joined the Soviet NKVD and whitewashes this decision in his story as being the lesser evil, and because he wanted “revenge against the Nazis.” William Forstchen in his forward to the 2006 edition put it this way:

Toward the end of the war, he was recruited by the Soviet N.K.V.D. And served as an officer. Gray says in his defense that his sole mission was to hunt down those who inflicted the Holocaust, and he deserted when he realized they were the mirror image of the other side.

I can imagine he inflicted plenty of damage of his own on defenseless Poles and Germans in enacting his revenge. According to Wikipedia, his job was to break up the Polish anti-communist underground in the area of Zambrów. Today, on Gray’s Facebook page, you can read:

At 17, Martin is the head of the biggest smuggling organisation of the Warsaw ghetto. He is eventually caught by the Germans and recruited as a Sonderkommando in the infamous Treblinka death camp. All of his family is exterminated there. He manages the impossible feat of escape and participates in the uprising of the Warsaw Ghetto where his father is killed before his eyes.

Consumed with revenge he joins the Soviet Army and becomes the youngest captain at 24.

Let’s understand the Warsaw ghetto was established in October and November, 1940, when Grajewski was 18 1/2 years old, so his claim to be a mere 17 in the ghetto is false. Plus, if he emigrated to the US in 1946, at the age of 24, he could not have first become an NKVD captain in that same year.

The same with his claims about being a Sonderkommando at Treblinka and escaping from there, not just once but many times … and after his final, successful escape to return to the Warsaw Ghetto to participate in the uprising before he becomes a captain in the Soviet Army. Whew! What a hero! According to several holocaust historians, the Treblinka part especially is not true.

But this doesn’t slow down the continuing advancement of his brand. The Facebook page tells us about a new documentary in the works based on the biography that it says has had 30 million readers! It’s titled A MAN. Naturally, his “amazing” life has already been put on film: For Those I Loved (screenplay by Max Gallo), starring Michael York and Brigitte Fossey. It was also broadcast as a mini-series during the 1980’s in Europe. A second, shorter film was made by Frits Vrij : Seeking Martin Gray.

Max Gallo wrote the book that Gray says he never read!

The original book cover, issued in 1971. Gallo was prominently given credit then, but in more recent times his name is no longer featured.

But before I go any farther, you need to know that Grajewski didn’t even write his own fabulous story. The author is Max Gallo, a French politician/historian who was a Communist until 1956; later he switched to the Socialist party. It seems it was Gallo’s idea to write the book but he didn’t begin until after Grajewski had emigrated to the U.S , made a fortune in the 1950’s producing fake antiques in New York City, then moved to France with a wife and child in 1960.

The great tragedy of Gray’s life is not found in the stories of his experience in the Warsaw ghetto and the Treblinka “death camp”, but in the death of his wife and four children in a 1970 house fire that took their lives but which he survived. That was harsh reality, while the Warsaw-Treblinka stories are fiction. It was after the loss of his family that he came out with the holocaust tales, very likely at the suggestion of his friend (or acquaintance?), Max Gallo.

In the 1971 original edition of “For those I loved,” a forward written by his neighbor and friend in France, David Douglas Duncan sheds some light:

“Martin Gray never talked about himself—not before the fire. Never a word revealing where he came from or about his family, or how he lost one eye. For some reason—perhaps it was his accent—I always assumed he’d been born in Russia. But then there were references to Berlin and counterespionage and the American army, and that small-boy grin when he confessed to mass-producing haute époque chandeliers in the basement of his Third Avenue antique shop; chandeliers designed by his luminously beautiful Dutch wife, Dina, who rode herd on the taciturn little Puerto Rican in the basement.”

This does more than suggest that Gray’s holocaust story came late, and was done with the same mentality that dreamed up the fake antiques business. It was Gallo, who was also the ghostwriter for Papillon, the “autobiography” of French convict Henri Charriere which was made into a blockbuster 1973 movie, who brought his exceptional writing skill to Gray’s story, and intended a similar success.

Max Gallo, the ghostwriter of “For those I loved,” the story of Martin Gray.

After Gray and his wife moved to the French Rivera with their one child in 1960, then had three more children — living an idyllic life in a large 300-year old farmhouse near the town of Tanneron — the tragic fire swept it all away in 1970. In the very next year, Gallo’s book was released, with the English translation coming out in 1972. Very fast work by M. Gallo … which is hard to fathom considering Gray’s intense personal pain at the time … but it was very possibly therapeutic.

In their book Treblinka, C. Mattogno and J. Graf point out that in an introduction to the 1971 For Those I loved (which does not appear in the 2006 version), “co-religionist” Gallo describes his writing process thusly:

“We saw each other every day for months. […] I questioned him; I made tape recordings; I observed him; I verified things; I listened to his voice and to his silences. I discovered the modesty of this man and his indomitable determination. I measured in his flesh the savagery and barbarism of the century that had produced Treblinka. […] I rewrote, confronted the facts, sketched in the background, attempted to re-create the atmosphere.”

From this it is clear Gallo is the author, sounding very much like Elie Wiesel when he talks about listening to the silence. And, like Wiesel and Buchenwald, we do know that Gallo totally invented the portion of Gray’s story dealing with Treblinka because industry-respected holocaust writer Gitty Sereny wrote the following about Gallo in her 1979 essay, “The men who whitewash Hitler”:

During [my] research for a Sunday Times inquiry into Gray’s work, M. Gallo informed me cooly that he ‘needed’ a long chapter on Treblinka because the book required something strong for pulling in readers.

If that’s not enough, she also wrote:

When I myself told Gray, the “author”, that he had manifestly never been to, nor escaped from Treblinka, he finally asked, despairingly: “But does it matter?” Wasn’t the only thing that Treblinka did happen, that it be written about, and that some Jews should be shown to have been heroic?

Sereny is concerned about Jewish lies “helping the revisionists.” She admits that “there have been books and films which were only party true, or even were partly faked. And unfortunately, even reputable historians often fail in their duty of care.” (She brings up Martin Gilbert as an example.) She continues, “But untruth always matters […] Every falsification, every error, every slick re-write job is an advantage to the neo-Nazis.”

At the end of the article, she declares, “One other thing assists the revisionists: many Jews, including survivors from the Warsaw Ghetto and Treblinka, are unwilling to bear witness and expose people like Gray for what they are.” What Sereny fails to say is that this is because liars don’t expose liars. Every surlievor account of Treblinka is false, as are most accounts of the Warsaw Ghetto. Sereny wants to believe it all happened as stated in the official narrative, but she is enough of a scholar to be embarrassed and angry by fakery that can be exploited by revisionists. So in 1979 she wrote the above-mentioned article in the very pro-Holocaust New Statesman. I want to mention that Dr. Robert Faurisson wrote a letter to the New Statesman commenting on this very article, which you can read here.

Gitta Sereny is not alone in denouncing Martin Gray as a fraud

Sereny, who is Jewish through her mother, has called “For those I loved” a fraudulent book. She is not the only Jew who has done so.

Graf and Mattogno tell us:

“Even anti-revisionist authors like the French Jew Eric Conan, who speaks of a work “well-known to all historians of this epoch as fraudulent,” [L’Express, February 27, 1997] have castigated M. Gray ‘s hackwork as a blatant falsification.”

At the French web site Enquete & Debat, the holocaust-believing editors have also called Martin Gray’s book a fraud. They say that Pierre Vidal-Naquet called Gray a liar in 1983, writing in Le Monde:

“Max Gallo has rewritten a pseudo-testimony by Mr. Martin Gray that, exploiting a drama about his family, totally invented a stay in an extermination-camp in which he had never set foot.”

Jewish writer Blake Eskin wrote about Martin Gray in his very successful book about another fraudulent holocaust memoir by Binjamin Wilkomirski: A Life in Pieces. According to reviewer Allyssa A. Lapin:

He said Gray’s book first appeared in France in 1971, where it sold 250,000 copies. It was then translated into 18 languages, becoming what Eskin called “an international sensation.”

However, as Eskin reports, before the book was published in English, the London Sunday Times ran an investigative report questioning its veracity. […] none of the survivors contacted by the London Sunday Times remembered Gray. The elaborate train station he described seeing on his reputed September 1942 arrival at Treblinka was actually constructed several months afterwards. […] “It was impossible to see the things Gray said he saw in Treblinka in the autumn of 1942,” one Treblinka survivor told The Times.

[…] Although Gray threatened to sue the Times, reiterating his claim to have been in Treblinka, according to Eskin he never actually filed a complaint. Subsequently, as Eskin reported, Warsaw uprising survivors interviewed by The New Statesman similarly questioned Gray’s “recollections.”

Gray’s French publisher, Editions Robert Laffont, refused to research the allegations, and the U.S. and U.K. publishers also published their editions–and, later, in paperback, which was followed by a film. Only the German publisher halted the presses pending its own research results.

Finally, to top it off — There is a Captain Waclaw Kopisto of the elite Polish Cichociemni unit, who took part in the raid on the German prison in Pinsk on 18 January 1943. In an interview with the Polish daily newspaper Nowiny Rzeszowskie (Rzeszów News) on 2 August 1990. he was shown the wartime photograph of Martin Gray (a.k.a. Mieczysław Grajewski) and said he had never seen Grajewski/Gray before in his life.

Yet Gray/Gallo described his participation in this raid in his autobiographical book that we’re discussing.

Kopisto stated that among the sixteen Polish soldiers in his partisan group there was in fact a Polish Jew from Warsaw by the name of Zygmunt Sulima, his own long-term friend and colleague after the war. No man like the one in the photograph of Gray ever belonged to their unit. Kopisto said:

“For the first time in my life I saw Martin Gray in a 1945 photo, which was published in March 1990 in Przekrój magazine (…) There were only sixteen of us participating in the 1943 Pińsk raid, and he was not among us.” [“Kim jest Martin Gray?” (Who is Martin Gray) Nowiny Rzeszowskie (The Rzeszów News daily), Nr 163, 1990]

It should be plainly obvious why it is that all holocaust surlievor books are considered “stories,” or even “memoirs,” but not history. For the publisher, their accuracy is the responsibility of the author; they don’t accept it as their own. It is only when one of these stories is exposed by someone with enough clout and credibility to get major publicity will the publisher take action and rescind the contract with the author. (As with Herman Rosenblat, another Polish Jew who was exposed by then-big-gun Prof. Kenneth Waltzer.) For the most part, in Holocaust literature anything goes. Only a few holocaust historians will ever speak up against fraudulent stories. Gitta Sereny is one. She has written about Jean Francois Steiner’s book Treblinka:

Steiner’s book on the surface even seems right: he is a man of talent and conviction, and it is hard to know how he could go so wrong. But what he finally produced was a hodgepodge of truth and falsehood, libelling both the dead and the living. The original French book had to be withdrawn and re-issued with all names changed. But it retained its format of imagined conversations and reactions – ie pure fiction – incredibly remaining, nonetheless, in serious bibliographies.

Sereny, however, also looks past a lot of nonsense in order to hold to the official holocaust story line. For example, she herself changes the name of Aktion Reinhardt (which is the spelling the Germans always used) to Aktion Reinhard so she can claim it was named after Reinhard Heydrich — an absurd idea. But on some things she draws the line if she fears, as I’ve pointed out, that their lies are so obvious, and they are so popular, that they will help revisionists tear down the holocaust edifice. For her, Martin Gray is one of those, and I can only agree with her.

*Note: Surlievor = survivor who lies about what he/she survived.

6 Comments

Category Featured | Tags: Tags: Captain Waclaw Kopisto, Gitta Sereny, Martin Gray, Mattgno & Graf, Max Gallo, Mieczyslaw Grajewski, NKVD, Treblinka, Warsaw Ghetto,

Social Networks: Facebook, Twitter, Google Bookmarks, del.icio.us, StumbleUpon, Digg, Reddit, Posterous.

Sunday, May 8th, 2016

Elie Wiesel, right, in his office at Boston University with his Israeli editor and archivist, Joel Rappel, who announced the discovery of a Hebrew version of “Night” in an exclusive report to Haaretz.

BY CAROLYN YEAGER

The controversy about the origins of “Night” is given more fuel by the recent announcement of Dr. Joel Rappel that he found a 150-page, handwritten document in Hebrew in the unsorted mass of Elie Wiesel’s personal papers.

I wrote about Yoel Rappel’s relationship with Elie Wiesel two years ago. Wiesel selected this Israeli journalist, editor and media expert he has known for decades to have control over how his writings and life story will be presented to the public – meaning what will be presented and what withheld. While Boston University is going to house the Wiesel Archive, it is not in control of it. Wiesel brought Dr. Rappel to Boston, put him on the payroll as “visiting scholar”, then put him in in charge of the Wiesel archive project.

I will go into some detail about this “newly discovered document” but first I want to list the six (oh, that number always comes up, doesn’t it?) versions of Night. They are:

1) 1954 – The original Yiddish manuscript, 862 typed pages, (No one has ever seen this, but more on that later)

2) 1955 – The edited and published Yiddish Un di velt hot geshvign – 245 book pages in Hebrew characters, not our alphabet

3) 1958 – La Nuit, original French – about 120 pages

4) 1960 – Night in English, Stella Rodway translation from French – 107 pages

5) 2006 – Night in English, Marion Wiesel new translation with numerous changes – 112 pages

6) late 1950’s, discovered in 2016 – Night in Hebrew, handwritten by Elie Wiesel – 150 pages (unfinished? – no one has seen this one either)

Which one have you read? They are all different, except for numbers 3 and 4 which are identical in content; thus it’s actually more accurate to say there are five versions, but I’m sticking with six. This latest discovery (#6) seems closest to number two in content, and, in fact, the content is not new if you are familiar with the non-fictional books Wiesel has published over the years, in which all these ideas have been expressed. The Haaretz report written by Ofer Aderet contains the following quotes from the “Hebrew Night”, probably given to him by Rappel. These are passages you won’t find in your conventional Night (#3,4 and 5).

“We believed in miracles and in God! And not in fate … and we [fared] very badly not believing in fate. If we had, we could have prevented many catastrophes. There is no longer a god in the heavens; he whispered with every step we put on the ground. There is no longer God in heaven, and there is no longer man on the earth below. The universe is divided in two: angels of death and the dead.”

And

“I stopped praying and didn’t speak about God. I was angry at him. I told myself, ‘He does not deserve us praying to him.’ And, really, does he hear prayers? … Why sanctify him? For what? For the suffering he rains on our heads? For Auschwitz and Birkenau? … This time we will not stand as the accused in court before the divine judge. This time we are the judges and he the accused. We are ready. There are a huge number of documents in our indictment file. They are living documents that will shake the foundations of justice.”

Also

“Eternal optimists … it would not be an exaggeration on my part if I were to say that they greatly helped the genocidal nation [Germany -cy] to prepare the psychological background for the disaster. In fact, the professional optimists [among the Jews -cy] meant to make the present easier, but in doing so they buried the future. It is almost certain that if we had known only a little of the truth – dozens of Jews or more would have successfully fled. We would have broken the sword of fate. We would have burned the murderers’ altar. We would have fled and hidden in the mountains with farmers.”

This is so disingenuous because Wiesel writes on many occasions that warnings were received but not believed, even by his own father (who was an optimist) because the Jews didn’t want to take action that would discomfort themselves. His own family, he has written, refused help from Christians who wanted to hide them. They did know about the deportations, but they hoped it would pass them by or the Russians would get there first.

“We didn’t know a thing [in Europe], while they knew in the Land of Israel, and they knew in London, and they knew in New York. The world was silent and the Jewish world was silent. Why silent? Why did it not find it vital to inform us of what was going on in Germany? Why did they not warn us? Why? I also accuse the Jewish world and its leaders for not warning us, at least about the danger awaiting us in ambush so that we’d seek rescue routes.”

This paragraph is especially full of lies, and the biggest lie of all is that there was an extermination waiting for Jews. It was not true, no one believed that or feared that, they knew everything anyone else knew. They didn’t know about “gas chambers” because there weren’t any. Wiesel is just looking for someone to blame after the fact. The same is true of the following paragraphs, although his seething hatred can’t be disguised any longer:

“All the residents stood at the entrances of their homes, with faces filled with happiness at the misfortune they saw in their friends of yesterday walking and disappearing into the horizon – not for a day or two, but forever. Here I learned the true face of the Hungarian. It is the brutal face of an animal. I wouldn’t be exaggerating if I were to say the Hungarians were more violent toward us than the Germans themselves. The Germans tended to shoot Jews.” [They never shot him or any of his friends or family, did they? -cy]

“At the end of the war, I refused to return to my hometown because I didn’t want to see any more the faces they revealed behind their disguises on that day of expulsion. However, from one perspective, I am sorry I didn’t return home, at least for a few days, in order to take revenge – to avenge the experts of hypocrisy, the inhabitants of my town. Then it would have been possible to take revenge!”

One last passage included in the Haaretz report is one that is not new; it has received a lot of attention in recent years, even by Wiesel himself. However, the wording here is not the same as in the Yiddish text; Wiesel wrote it differently each time, trying to better express it so his orthodox Jews don’t come off looking bad. Of the trip by rail to Auschwitz, Rappel says, Wiesel wrote in detail in the archived text:

“Under the cover of night, there were some young boys and girls who had sexual intercourse. The initial impact of the disaster was sexual. The tension of the final days sparked the desires that now sought release. And the heat also added its own touch, so that the sexual scenes did not provoke protest in the carriage. Eat, drink and be merry, for tomorrow we die.”

This is a different Wiesel than the author of La Nuit, which was more the product of Francois Mauriac and the publisher Jerome Lindon. La Nuit was written for the goyim, the Christian West, but it doesn’t say everything Wiesel had originally said to his fellow Jews. Later, he put much of it in other books, essays and interviews, and now it’s coming to us in this “new, expanded version of Night.” Why now? Well, Wiesel will be 88-years old on September 30th and is apparently not in the best of health, so people like Dr. Rappel are getting his legacy in order.

Night is a flexible tale that Wiesel adds to and subtracts from at will

Even Rappel is left to speculate as to why Wiesel decided not to publish this work in Hebrew for Israeli readers, but instead shelved it and agreed to a translation by Haim Gouri of the French La Nuit into Hebrew. Rappel says. “I wondered if someone wanted to make it disappear and get rid of it.”

“This is the version of ‘Night’ that Wiesel wanted the Israeli reader to see. He didn’t write it for anyone else. Therefore, it was so important. Wiesel knew that many Holocaust survivors from Auschwitz and Buchenwald, as well as many Jews living in Israel, would read this version, and so he put more emphasis on the Jewish aspect.”

If that’s true, why did Wiesel store it away, deep in his mass of papers? “He knew that, someday, someone would find this manuscript and leave it for the following generations,” believes Rappel.

This last sentence gives away the nonsensical nature of this whole “discovery” of a lost manuscript. If Wiesel wanted survivors to read it, he wouldn’t at the same time hide it from them, allowing only future generations to read it. Seems to me he decided not to compete with his already published version, maybe at the request of his French publisher. At the time he was supposedly writing it – the late 50’s – the English language Night had not yet been published. But Wiesel is perhaps not satisfied with what is left of his “epic” in La Nuit and begins preparing a Hebrew version that reinstates some of his original. What is described here by Rappel as a “hugely different” version of Night is very similar, in fact, to the 245-page Yiddish Un di velt hot geshvign (And the world remained silent) which Wiesel says he wrote in April 1954 on a ship heading for Brazil. [All Rivers Run to the Sea: Memoirs (New York, 1995), pp. 239-40] It appears he was mining that book – returning to what he originally wrote and was published by Mark Turkov as part of the 176-volume Polish Jewry Memoirs Series [Dos poylishe yidntum].

I have always suspected that Wiesel knew about Turkov’s publishing operation in advance of his trip to Brazil since he had close relatives in Buenos Aires who would have informed him about it. He could have used the trip to Brazil to take his manuscript to Turkov in Argentina. The scenario could go like this: Wiesel had been working on his grand “testimony” for several years already and had completed it. On the boat to Brazil, he worked on finishing touches. That was in April 1954. One year later, in May 1955, he meets Francois Mauriac, who urges him to write about his concentration camp experience. Without telling Mauriac he has already done so, he keeps up his friendship with the famous Catholic writer and when the published Un di velt hot geshvign arrives in December 1955, he translates it into French and shows that to Mauriac. Or … another possibility. Did Wiesel not give his “only copy” to Turkov because all along he had a copy at home in Paris? This makes more sense because it is impossible to credit any sane person giving their only copy of a precious manuscript to a stranger in a foreign land, even if he were a publisher. This question has now been answered for me, since it’s come to my attention that in a 1978 interview with John S. Friedman, published in The Paris Review 26 (Spring 1984), Wiesel said he still had the original manuscript:

INTERVIEWER

Have you destroyed the original nine hundred pages of Night?

WIESEL

No, I have them. Others I destroy; Night is not a novel, it’s an autobiography. It’s a memoir. It’s testimony. Therefore I believe it should be kept and one day I may publish it because I have no right not to. It’s not mine. [“it” refers to the ‘original 900 pages’ he believes should be kept -cy]

Contradicting this in his 1995 memoir, he wrote:

In December [1955] I received from Buenos Aires the first copy of my Yiddish testimony “And the World Stayed Silent,” which I had finished on the boat to Brazil. The singer Yehudit Moretzka and her editor friend Mark Turkov had kept their word—except that they never did send back the manuscript. Israel Adler invited me to celebrate the event with a café-crème at the corner bistro. [ All Rivers Run to the Sea, p. 277]

Of course, if Wiesel had one at home, they wouldn’t need to send it back to him. Except … on page 241 he had also written: “It was my only copy, but Turkov assured me it would be safe with him.” So which is right? Rappel quotes from Wiesel’s memoir several times, thus I believe he would think it necessary to go with the memoir over the interview. However, it’s a major contradiction and I wonder if he would be willing to attempt an answer to it.

So right now the burning question is: Will Dr. Joel Rappel find the original typewritten 862-page manuscript in Elie Wiesel’s 330 boxes of material, as he found the 150-page handwritten Hebrew Night? It should be there since Wiesel told Friedman he kept it. Or did he destroy it between 1978 and 1995 because he no longer believed it should be kept? Or is Rappel keeping it hidden for reasons of his own, perhaps because of the many contradictions that undermine the integrity of Wiesel’s memoir? The only thing we know for certain is that we’re dealing with dishonest people so we can’t expect we’ll ever really know. Most ‘holocaust survivors’ wait for all witnesses to die before they tell their story and Wiesel is no exception.

This is my first question, but there are others, such as: since Un di velt hot geshvign is a published book, those who know Yiddish can easily read it, why therefore does Rappel ignore it? I have included portions of it translated to French and English here at Elie Wiesel Cons The World. Naomi Siedman, a professor of Jewish studies, has written a well-known article quoting from it, as have others. Yet Rappel speaks of these passages as if they were previously unknown. Well, to the general public, they are.

The archived version of “Night” is hugely different to the published one. It contains entire sections that don’t appear in the finished book, as well as different versions of pieces that were included.

True enough, but is Rappel not familiar with the Yiddish book that Wiesel claims to have written or does he want to discourage attention to it?

Siedman also noted significant differences in the ways each book reveals Wiesel’s writing process: In the Yiddish memoir (#2), he starts to write immediately after liberation, while the French text (#3) says he started writing only after a 10-year vow of silence. I have discussed Siedman’s commentary here.

Night: Clearly a work of fiction

An article in the Jewish Journal from 2013 gives an interesting insight into Wiesel’s insistence that his book Night is in no way fiction.

‘Holocaust scholar’ Michael Berenbaum has known Wiesel well for 35 years. Berenbaum wrote his doctoral dissertation in the 1970s about Wiesel’s work and later worked with Wiesel on the council that created the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C., in the 1980s. He declared that “Wiesel’s moral power base is directly related to the moral stature that has been accorded to the Holocaust.” (That is, without the public’s belief in the ‘Holocaust’, Wiesel is nothing.) Berenbaum volunteered to Jonah Lowenfeld:

“If you want to get Wiesel angry, all you have to do is call ‘Night’ a novel instead of a memoir.”

In that same article, Gary Weissman, an assistant professor of English at the University of Cincinnati, said he finds Wiesel’s celebrity a distraction.

“I have found that Wiesel tends to be ‘celebrated’ rather than questioned in any probing way. Many are investing in treating — and experiencing! — Wiesel as a holy figure, rather than as a complex and real human being.”

How very true. And it’s guaranteed to get worse, what with his ever-advancing age. I don’t have a clue what could put the genie back in the bottle when it comes to the over-inflated reputation of this man, other than taking the media out of the hands of Jewish monopolies.