Posts Tagged ‘Max Hamburger’

Wednesday, February 13th, 2013

by Carolyn Yeager

The interview with psychiatrist Max Hamburger that appeared in the March 2012 Dutch magazine Aanspraak was translated into English for me by Hasso Castrup. Some things that Hamburger said are revealing of his overall honesty when it comes to his statements about “the Holocaust.” Being a “holocaust survivor” who appears in the famous photograph is, after all, his only claim to fame.

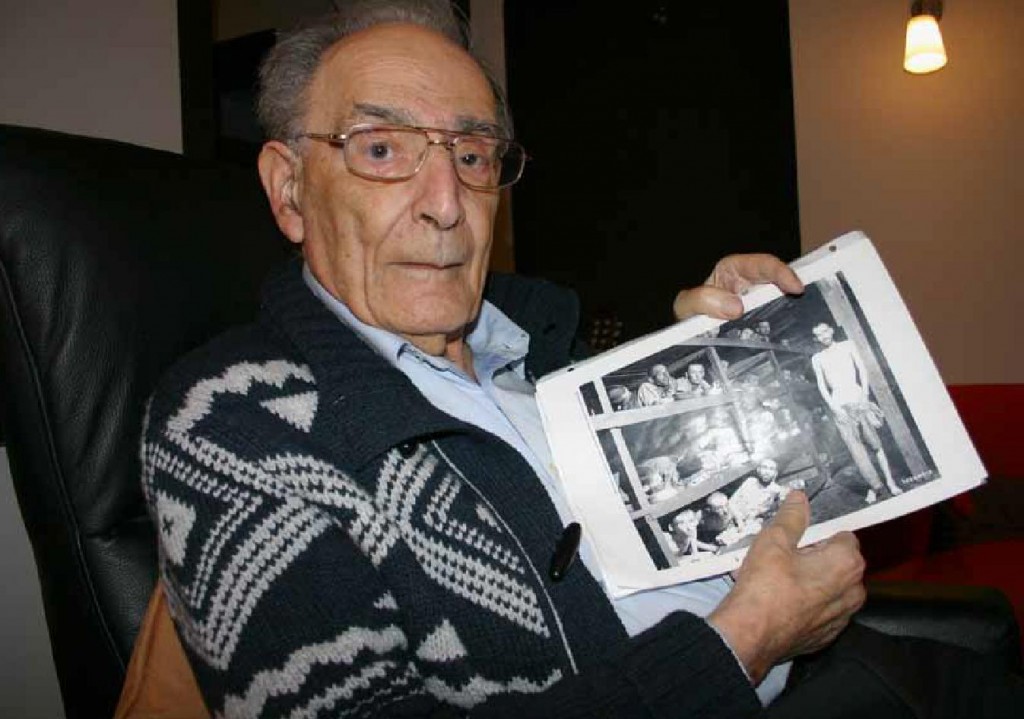

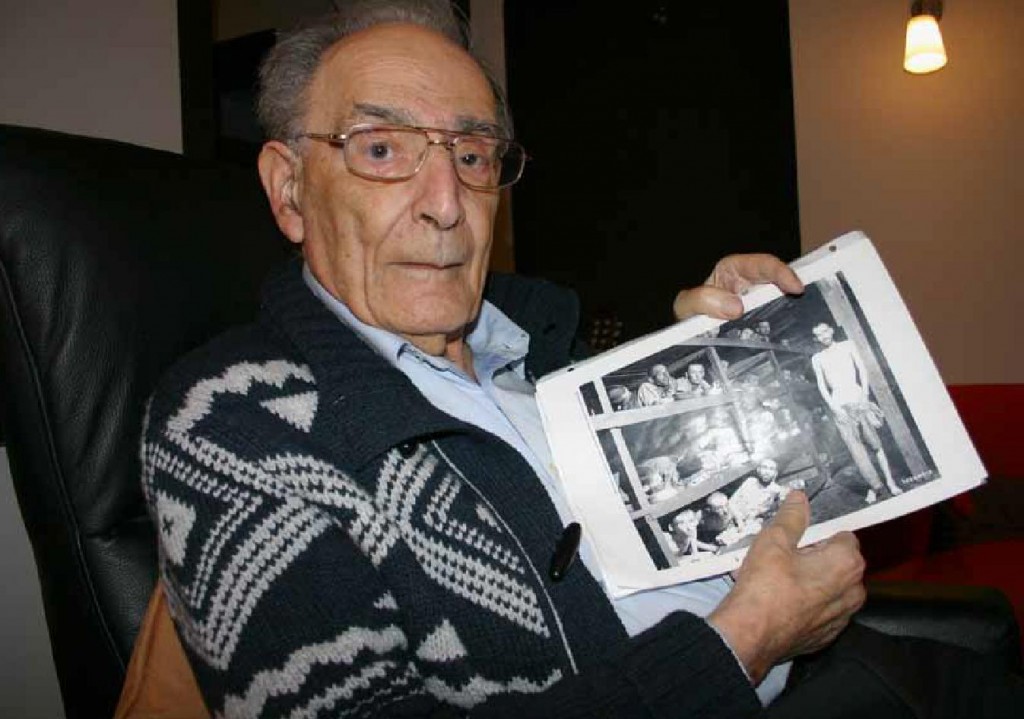

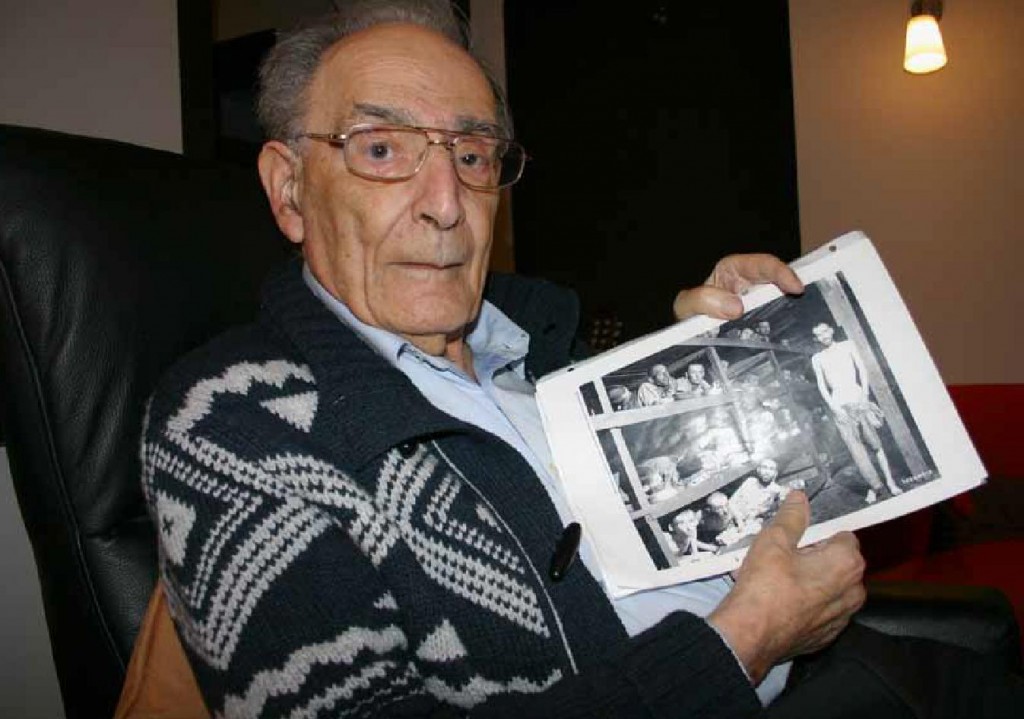

Max Hamburger in 2012 pointing to himself in the Famous Buchenwald Lie-beration Photo from 1945 (Source: Aanspraak magazine)

Max Hamburger in 2012 pointing to himself in the Famous Buchenwald Lie-beration Photo from 1945 (Source: Aanspraak magazine)

I’ve already reported in a previous article (scroll down to end) that his father was an Amsterdam diamond merchant, Hartog Hamburger, who died from a bizarre accident when Max was only four years old. His mother, a fashion designer, worked even harder after that and often left him with his grandparents. When Max was ten, his brother died of leukemia, leaving Max alone with his mother. This is quite a lot of trauma in the first ten years of life, which couldn’t help but leave a mark on his psyche.

He says his brother’s death is what inspired him to study medicine, beginning in 1938 when he was 18. But in 1942, further public education was denied to him because he was Jewish. His job with the Jewish Council (Judenrat) allowed him to remain immune to deportation to Westerbork by getting a special stamp on his Ausweis (ID). In the summer of 1942, he went to work as an intern at the New Israelite Hospital, where he learned that when the substance ‘Pyrifer’ is injected intravenously it will cause high fever similar to what one gets with malaria or typhoid. Hamburger began injecting this into the Jewish patients so they would be declared unfit for deportation.

This, of course, raised suspicion among the Germans and Hamburger says in June 1943 the New Israelite Hospital was raided, in order to be emptied. He and other medical personnel hid patients under laundry and in the morgue, and led seriously ill patients into hiding (?). He is proud to describe himself as part of the Resistance and says he was later awarded with a memorial cross because of it. He tells a story that describes how in August 1943 he once again escapes deportation, but I’m not repeating it because there is no way to assure it’s true.

Working with the Resistance

He then moved to the Jewish Handicapped (Asylum) at Weesperplein, where he and other doctors again tried to”save” as many patients as possible by declaring them ill with contagious diseases. He says at the Portuguese-Israelite Hospital people in mixed marriages were to be sterilized. Along with most of the staff, he refused to cooperate and went through a hidden door into a neighboring villa and went into hiding. He and his girlfriend were married by a rabbi; they were both fully into the Resistance now. His mother was also brought to where he was, but she quickly hid herself elsewhere.

He says that “shortly afterwards we were betrayed and arrested, interrogated and deported to Westerbork. My mother was also betrayed.” On Sunday, February 6, 1944, he saw her for the last time in the penal barracks at Westerbork. They fell into each other’s arms and cried. But then … “In Auschwitz I met a fellow radiologist who was deported together with her. He told me that my mother was gassed on March 6, 1944. I arrived there on February 10, 1944 (his 24th birthday, but he doesn’t mention it), but did not see her again.”

Since we know there were no gassings at Auschwitz – this is a dead giveaway that he’s telling a big lie, although he’s putting the lie in the mouth of an unnamed “fellow radiologist.” This is a trick that is used often by so-called witnesses and “survivors.” The so-called informant should always be named; if they can’t name the exact source of the information, they should not be believed.

At Auschwitz, he at first failed, then succeeded in becoming recognized as a doctor. He began on a work detail where he says he was “poorly dressed in the icy cold damp weather, the work meant a maximum survival of 3 months.” (We hear so often that the life expectancy was “3 months,” but why did most inmates not only live until liberation, but into old age after it? Hamburger himself is 93 years old – Feb.10, three days ago, was his birthday.) As a doctor, he supervised the cleaning of the barracks during the day, in the afternoon handed out soup, evenings he did lice control. What’s so hard about that? Yet he says that in April he developed a fever, and on May 1st managed to avoid the medical inspection (a strange story of ‘luck’) in order to be included in a transport of Hungarian “forced” laborers headed to Silesia. He says this “saved his life” (considering his 3 months were almost up, don’t you know).

According to this, Hamburger was at Auschwitz from Feb. 10 to May 1, 1944 – a little less than three months. This was the usual length of quarantine at Birkenau for those who were then sent to other camps as labor. During the 2 to 3-month quarantine period the inmates did not work, so I do think his account has quite a bit of invention in it so as to not sound like quarantine. His mother would also have been in quarantine and he would not have seen her there, being the men and women were strictly segregated into separate camps. This is the usual situation from which “survivors” claim their relatives were gassed, the information so often coming from a nameless fellow inmate; sometimes from a “sadistic guard.”

After Auschwitz, the story gets more confusing

The train took them to Gross Rosen, where an old factory was assigned as their hospital. He says “we” had to vaccinate everyone against typhus in February 1945. Their only hope were reports of advancing Russians and Americans, which they knew of because a fellow prisoner secretly listened to the radio. At the evacuation of the camp they had to walk in the snow to the Czech Republic. From there they were taken by train from Prague to Flossenbürg camp in Bavaria.

According to USHMM, Gross Rosen camp was evacuated in early February ’45 and “about 40,000” from the main camp and sub-camps had to march west. This is a lot of inoculation to be done in a few days. But more important, the 9-month period he spent at Gross Rosen between May 1944 and February 1945 is blank. May 1944 coincides with the time of the large Hungarian deportation to Auschwitz; Hamburger says he was with a Hungarian labor unit that had already been to Auschwitz and sent out from there. Would not the new arrivals also have been sent out from there in like manner? From here on, his narrative remains very sketchy, and is mostly made up of vague horror stories.

He says, “The camp guards were shooting prisoners who were their live targets in the white landscape. Daily there were death sentences and prisoners were hanged before our eyes.” Yet the prisoners were needed to work in the quarries and Messerschmitt factories … and they had been innoculated in February against typhus, no doubt at some expense. So why would they be wasted as target practice for the guards? This is when survivor stories become really unbelievable. At the beginning of March 1945, he says they were deported to Ohrdruf, a work camp of Buchenwald. “Here were bombproof underground factories for assembly of V-weapons. After underground explosions with dynamite, we were to remove the big stones from the corridors by small-gauge trains.” But he doesn’t stay there. “We had to walk for four days and nights 80 km (approx. 40 miles) through the snow to Buchenwald.” Although he says he was practically “in a coma,” he’s clear about the dates and distances.

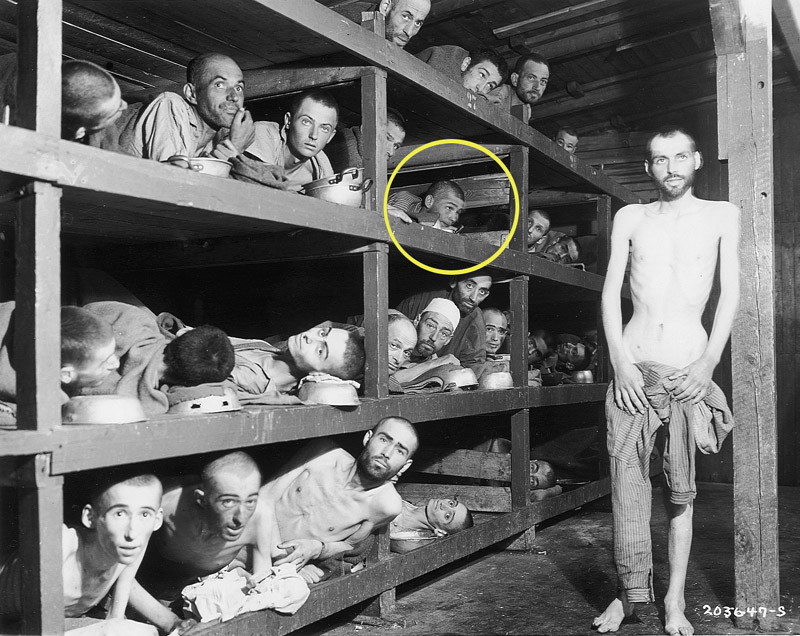

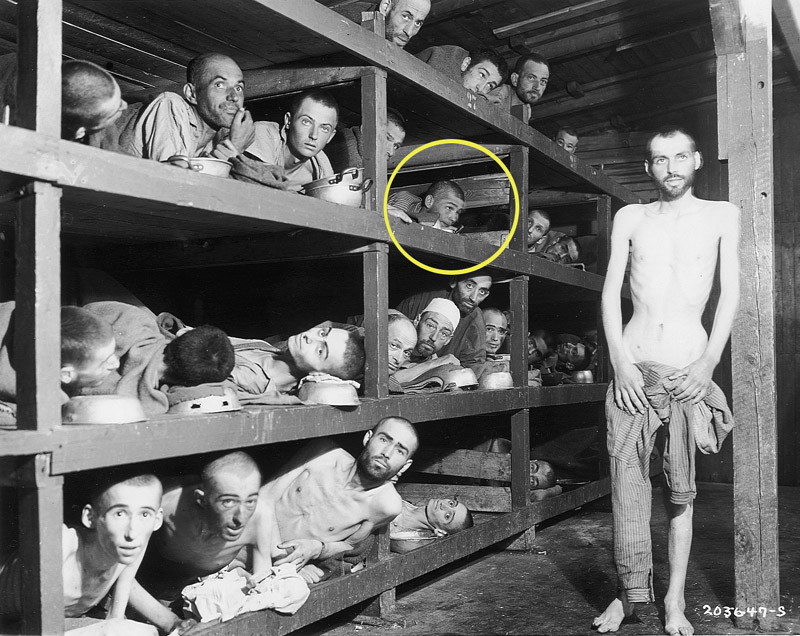

“On 11 April 1945, Buchenwald was liberated by the American army. Five days after the liberation our well-known picture (was taken). I lie down there, fourth from the left. As I lay there someone advised me to go to the hospital, because I otherwise would not survive. “If they do not record you, you go ‘under the grass.’ When an American goes by and sees you lying, he makes sure that you get recorded. And so I went. With DDT powder I was lice free. The lice and I got U.S. baby food! For me THAT was liberation. During a night in the hospital, I knew: ‘If I fall asleep, I’ll never wake up and I won’t be able to testify to what happened to us.’ I fought that night to the utmost against sleep and thereby I survived.”

From the beginning of March to April 11, Hamburger has nothing to say except that he spent 4 days walking from Ordruf to Buchenwald and that he was in the photograph taken on April 16. He doesn’t give the date that he arrived at Buchenwald. What he tells can be picked up from any number of accounts of the time period. Can we believe he was even at Buchenwald? Why was he in that barracks #56? How long was he there? Why did “someone” have to tell him to go to the hospital 5 days after the Americans arrived? All very implausible since he was a medical professional.

But beyond all this is the fact that the figure he says is him is indeed a retouched copy of the figure in the row above, 3rd from the left. He doesn’t claim any relationship to that person, who has been identified (inaccurately) by Yad Vashem Museum as Yehuda Doron or Yaakov Marton. This famous photograph has been proved to be a composite photo created by a U.S. military intelligence department to be used in the ongoing propaganda war against Germany and Hitler’s Third Reich, so everything about it is suspect.

The rest of what Hamburger said in the interview does not apply to the questions I have. Again, my primary question is: When did Max Hamburger first say he was in that photograph? Like so many others, it was not at liberation, nor in the years following. In fact, there is no information that I have found as to when this did occur. Why? Because it must be recent – too recent.

Concluding thoughts

In 1945, Max was 25. He wrote that he and the loyal wife he married when he was 22 were divorced sometime around or after 1957, and he is now with his third wife.

“For a long time I have been a psychiatrist and I have helped many war victims thanks to my own experiences. Until I could no longer afford to listen to them. Unfortunately I never found a psychiatrist who could help me. I regret that I was a bad partner in the previous marriages, but that’s because I was in the grip of the past I had lived through. I find it annoying when people make demands on me and I can get angry.”

I bet he could sure get angry with me! I am making demands on Max Hamburger to fill in the blanks in his “holocaust survivor” story. I don’t have any reason to doubt the early part of his story but, starting with his and his mother’s arrival at Auschwitz, there is much to question.

He is, from all appearances, a loyal Jew with the typical Jewish desire to avenge the “wrong” done to his people and the interruption and pain in his own personal life. Telling lies to accomplish this is not, therefore, a wrong in his eyes. A wrong for a wrong is, for Jews, a fair exchange … nothing to be ashamed of. This may even be how he counseled his patients.

2 Comments

Category Featured | Tags: Tags: Auschwitz, Buchenwald, Dutch Resistance, Gross Rosen camps, holocaust survivor, Max Hamburger, photo forgery, Westerbork,

Social Networks: Facebook, Twitter, Google Bookmarks, del.icio.us, StumbleUpon, Digg, Reddit, Posterous.

Tuesday, January 8th, 2013

By Carolyn Yeager

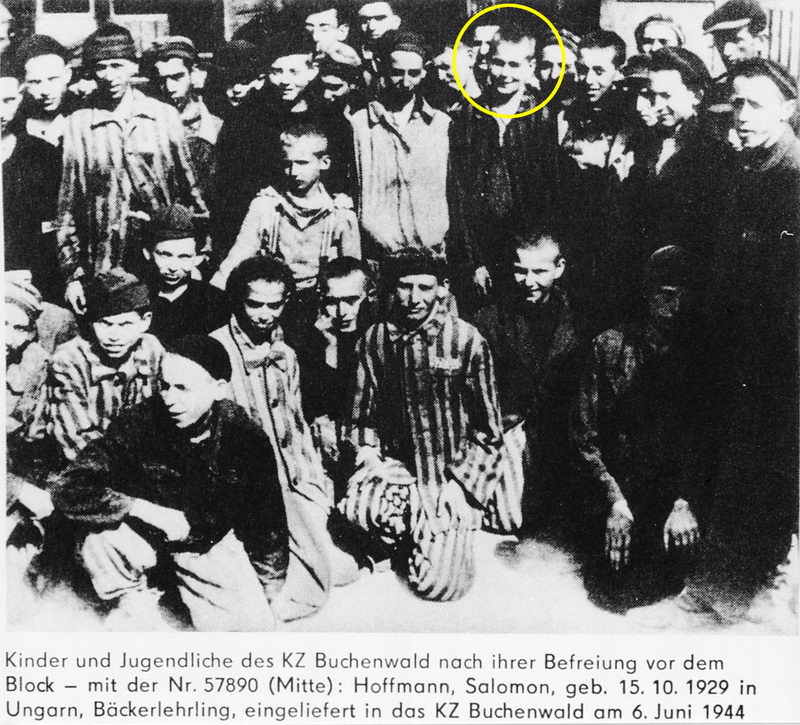

The man who now calls himself Naftali Prince (Fürst translates to Prince in English), and who was also known in childhood as Duro Forst, is the person circled in both photos below, taken at around the same time shortly after the Buchenwald “liberation” on April 11, 1945.

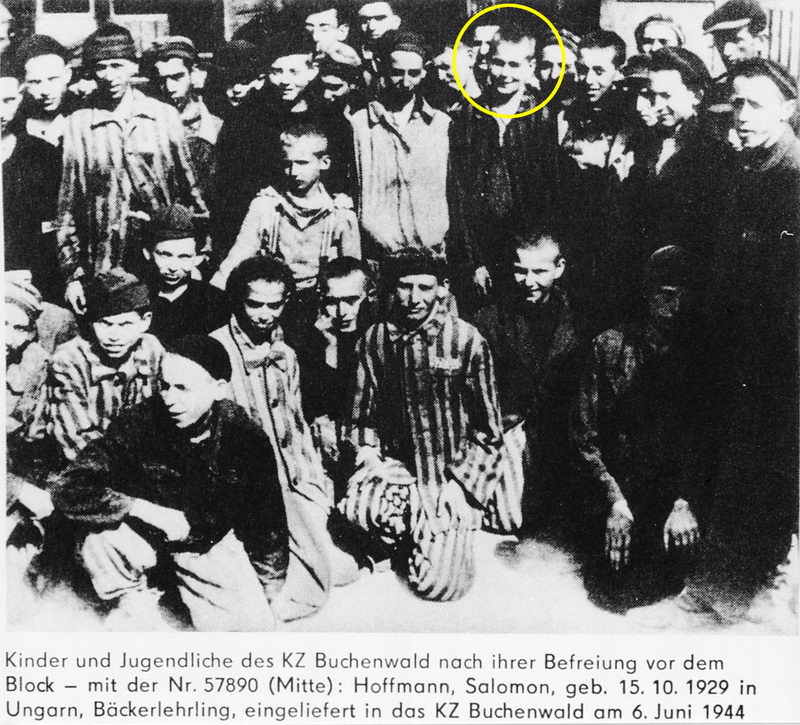

Above: “Buchenwald children on the release day. Naftali Fürst is marked in a yellow circle.” (As per Naftali’s website, http://furststory.com/English/Holocaust_Kinder.html)

Above: “Buchenwald children on the release day. Naftali Fürst is marked in a yellow circle.” (As per Naftali’s website, http://furststory.com/English/Holocaust_Kinder.html)

Below: “Buchenwald. Naftali Furst is marked with a yellow circle.” Can this be a 12-year-old boy? The man two rows directly below him is identified as being 25-yrs old.

Below left: “Our parents and us after the war” (As per http://furststory.com/English/YaldutMomDad.html) Naftali is to the left of his father, although he strongly resembles his mother, while his older brother takes after their father.

Why is it that he looks younger in the family photo, at age 13 or 14, than he does a year or two earlier in the barracks? Because it’s not him in the barracks, that’s why. Simply look at the difference in the forehead in the comparison of the two faces. The man in the bunk has a low hairline (short forehead). The real Naftali Fürst has a higher forehead. Thus he’s another one who succumbed to the temptation to join an exclusive club by falsely identifying himself in this famous photo. The holocaust museum people will never investigate and will never say otherwise.

Other evidence that refutes Fürst-Prince being in the photo

Naftali and his brother Shmuel (also known as Ďuro and Peter – their Slovak names) wrote a family recollection and published it sometime around 1998. In it, neither mentioned that Naftali was in the famous Buchenwald liberation photo. Naftali wrote in the Preface:

For over fifty years, my memories and emotions have been repressed deep in my soul.

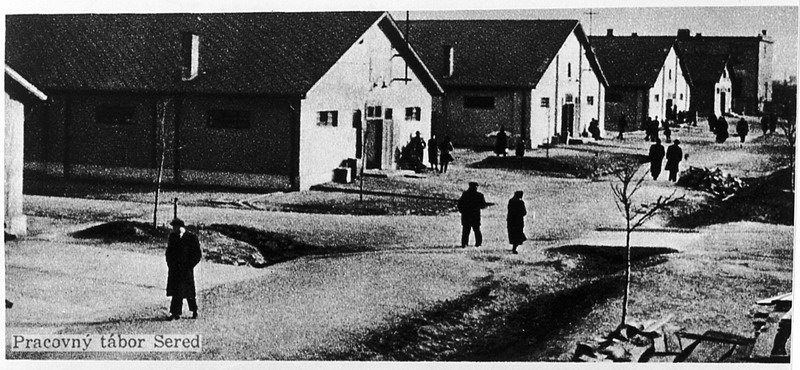

He was born in 1933; the brothers were five and seven in the fall of 1938. At the end of 1942 they moved into the Sered detention camp (photo below).

Of this, Naftali wrote that it

Of this, Naftali wrote that it

… was the most acute transition in the life of our family. We left behind a big house with a housemaid and nannies and a car, and moved into a tiny room.

Until the end of 1943, life in the camp went on in a relative stability. Until August 1944, the output of products manufactured in the camp contributed largely to the economy of Slovakia …

Beyond work, cultural events such as poetry readings, as well as soccer matches, were part of the agenda. Inside the camp, there was a small swimming pool. Every now and then we were permitted to go for a swim. Among young men and women, love affairs were flourishing.

The nearby hospital was an important institution. Prior to the war, there was a Jewish hospital in Bratislava. Its entire medical facilities were transferred to Sered. During our stay in the camp, Shmuel had an urgent appendicitis surgery in that hospital. Its proximity to the camp saved his life. By February 1944, Shmuel was thirteen years old. With great efforts and despite all obstacles, our parents managed to celebrate his Bar-Mitzvah.

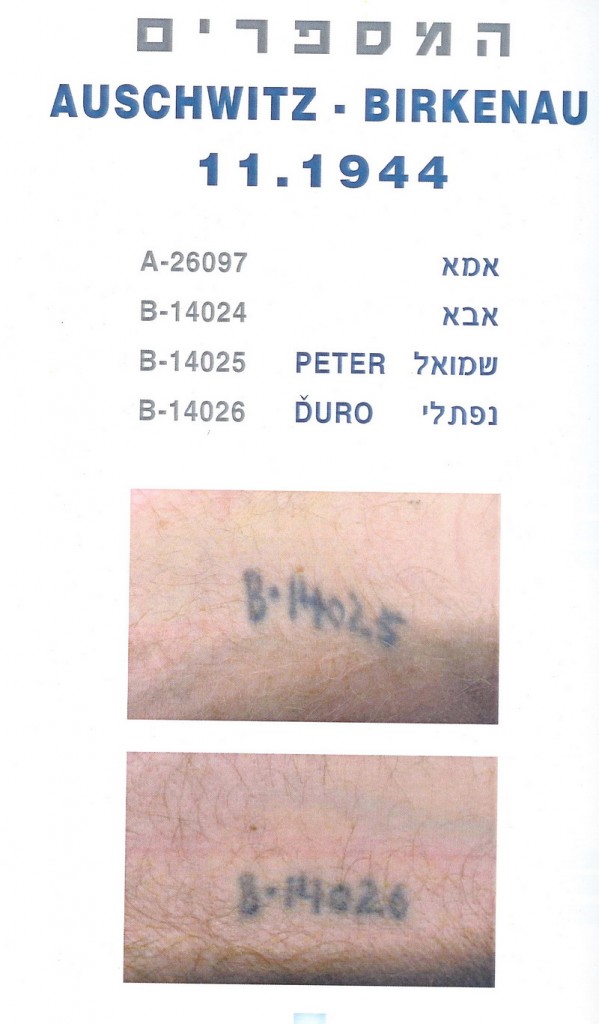

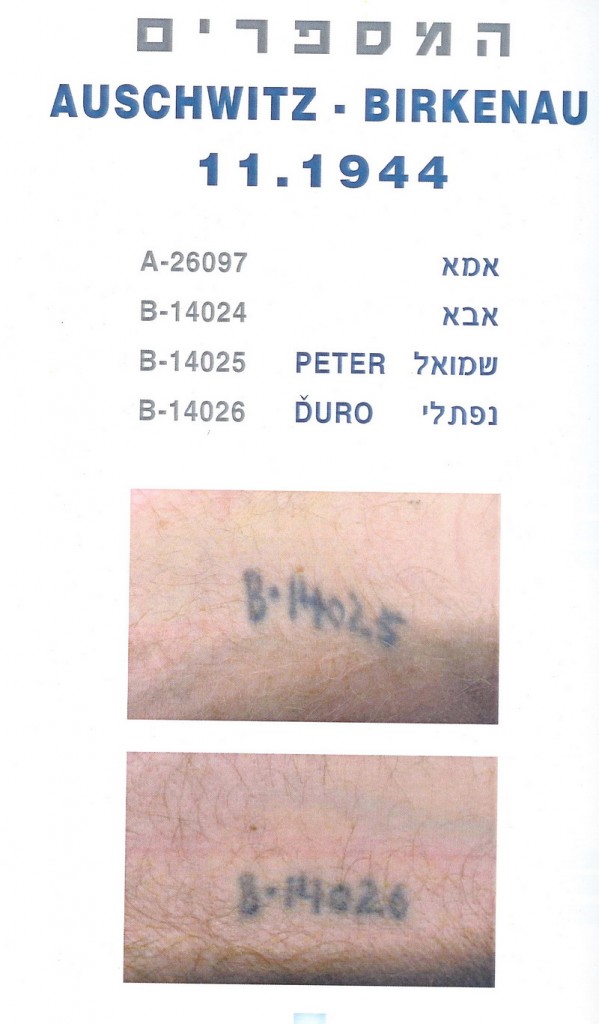

On November 2, 1944 the family was put on a train to Auschwitz-Birkenau. According to the story, the men got the following tattoos:

On November 2, 1944 the family was put on a train to Auschwitz-Birkenau. According to the story, the men got the following tattoos:

Dad’s number was 14024, Shmuel’s 14025, and mine 14026.

(The chart at right was created in Israel and may be truthful or may not; it is included in the family history.)

Move to the Kinderblock

After a short period, we were ordered to join with other children and youth, and move to the “Kinderblock”, the Children’s Block.

Naftali was just going on 12 years old and Shmuel was going on 14. In December they were moved to an agricultural farm near Auschwitz, at which there was little work for them to do.

On January 19, 1945 we were ordered to get ready for leaving the camp and a long march away. […] On the following morning, part of the farm equipment was loaded on horse-drawn wagons and the march begun: the wagons rolled in the front, while we marched behind them.

Naftali writes the march took 3 days and nights before they reached Breslau, followed by a day and a half train ride to Buchenwald. (This is considerably longer than the one-day march from Buna-Birkenau to Gleiwitz and train to Buchenwald that others described.) The brothers were eventually together in the children’s barracks, Block 66. After being there awhile, Naftali developed pneumonia and was transferred to a hospital. After recovering some, he says he was moved to a room in the Brothel where he enjoyed relative luxury. Then:

In the morning hours of April 11, 1945 we began hearing sound of artillery. While the frontline drew nearer and nearer, the underground rose up. On that very day Buchenwald was liberated. And where was I liberated? In the Buchenwald whorehouse! Not every twelve-year old child had such a privilege…

During the first days of freedom, there was a lot of disorder. As we were not allowed to leave the camp, we strolled aimlessly from one barrack to another. Then we went to see the crematorium and the torture cells, and finally we opened the clothes warehouse. There we wore SS uniforms.

It did not take long until we were organized into groups according to our countries of origin. Among the organizers was a man who pretended to be the brother of General Viest, a Slovak hero. He took care of the Czechoslovak group, Which a fortnight later was taken by trucks into Czechoslovakia. Upon our arrival in Bratislava, we were welcomed by the Jewish community, Which was already functioning.

Nothing is said about being photographed in Block 56 and having his image immediately displayed all around the world.

When did Naftali Fürst first decide he was in that photograph?

I would say it would have to be after 1998, after publishing the family story he wrote with his brother that is titled “Fürst Brothers.” Did someone suggest it to him or did his photographer’s eye detect an opportunity? As with all the others, the claim of being in this photo came many years later, not until the 1980’s or 90’s, and even into the 2000’s. There is a reason for this. Where are the pictures of them from that time? And where are the records? No one in that photograph was named at the time, so it is a free-for-all now to to claim yourself to be one of those faces.

After the war, Naftali studied photography in Bratislava and names his profession as Photographer. In 1949 he moved to Israel, where he still resides.

A passion for Remembrance and Revenge

“The 12-year-old boy in the 3rd row of the wooden bunks – that’s me,” says Naftali Fürst to anyone who will listen. In his hand he holds a famous photo that he almost always carries with him, because it has become part of his memory. “Inclusion in Buchenwald was the so-called death row,” recalls Prince. “I was so sick, almost on the other side.”

During the 7th Yad Vashem seminar of Remembrance in March 2004, Naftali Fürst told parts of his life story to a group of Austrian teachers. For nearly an hour he revealed fragments of his memories.

In the Preface to his family story, Fürst revealed his feelings that remain with him today:

Germans – I loathe the Germans of that era, particularly those who wore SS and Gestapo uniforms. Therefore, I decided to mention them only where it was absolutely necessary.

Max Hamburger and Nicholas Grüner (see previous posts on this blog), for no doubt similar reasons, are also anxious to speak about and embellish their long-ago ordeal anywhere they are invited. They receive great sympathy and have even become somewhat famous simply for being in the “famous photograph.”

“They didn’t know each other” at Buchenwald

“They didn’t know each other” at Buchenwald

Even though they all say they are in that picture taken on April 16, 1945, and Grüner and Fürst both say they stayed in the children’s Block #66, they did not know each other. The three men met for the first time when the now deceased journalist Ursula Junk brought them together on the 60th Anniversary of the liberation of Buchenwald in 2005.

On the occasion of the commemoration of Kristallnacht on November 9, 2006, they met again in Germany at the home of the artist Christiane Rohleder, in Much near Bonn. Invited by the Archivist of the Rhein-Sieg-Kries, Dr. Claudia Arndt, they each told the story of the 1945 photograph to the students — three painful biographies. If you believe it.

Brothers in spirit: Max Hamburger (from left), Nicholas Gruner and Naftali Fürst. Photo: Axel Vogel

4 Comments

Category Featured | Tags: Tags: Auschwitz-Birdenau Kinderblock, Breslau, brothel, Buchenwald Block 66, Buchenwald Lie-beration photo, Max Hamburger, Naftali Fürst, Naftali Prince, Nicholas Gruner, Sered detention camp,

Social Networks: Facebook, Twitter, Google Bookmarks, del.icio.us, StumbleUpon, Digg, Reddit, Posterous.

Friday, January 4th, 2013

By Carolyn Yeager

Max Hamburger, a Jewish-Dutch psychiatrist, is the man in the above photograph taken in 2012. He is 92 years of age.

Hamburger has identified himself as the fourth figure in the bottom row of the famous Buchenwald photo — the figure he is pointing to with his thumb. He was 25 years-old in April 1945 when the camp was “liberated” by American troops. I want you to notice right away the space between Hamburger’s nose and upper lip — it is unusually long. The face of the young man in the famous photo does not have that long space, but just a normal, or even short, distance between nose and mouth. This is facial structure that doesn’t change, which is one clue that tells me he is not the same person.

Born on February 10, 1920 in Amsterdam, Max began the study of medicine in 1938 and, as best I can make out from Dutch language sources, he was arrested in 1942 because of his activism in the Dutch Resistance and sent to Westerbork, a camp for political prisoners in The Netherlands. He ended up in Auschwitz and then Buchenwald, he says, taking the usual route. According to this page, he was suffering from TB, and also malnutrition, when the famous photo he’s holding in his hands was taken.

The blurb on the Flicker page also says “he only survived Auschwitz because he could work as a medical assistant.” One has to ask about all those who didn’t work as a medical assistant, but also survived and went to Buchenwald … and survived Buchenwald too without being medical assistants! This is the kind of meaningless tripe we are always given to explain why people survived “death camps.” This page also says he now (in 2008) lives in Belgium and gives talks about his wartime experiences. In other words, he advertises himself as a holocaust survivor who is in the Famous Buchenwald Liberation Photo, the one that Elie Wiesel is in. (See final section below)

It should be noted that Nicholas Grüner is in this photo too; he is the first person on the left in the bottom row and the only one of the three mentioned who actually looks like himself, and is himself. Yet the labeling of this photograph at Yad Vashem Holocaust Memorial in Jerusalem (below) gives three possible identities for this figure: Gershon Blonder, Josef Reich or Nicholas (Miklos) Grüner … as if it were in doubt. The other two are not shown to be in doubt: the fourth figure on the bottom is Max Hamburger; the seventh figure in the 2nd row is Elie Wiesel. It’s clear to me that Yad Vashem will eventually deny that Nicholas Grüner is in the photo at all, and thus his claim that Elie Wiesel was not in the camp (or the photo) will be weakened. These people are nothing if not devious … and they accomplish their objective in a gradual manner. According to Yad Vashem …

Second bunk:

Second bunk:

First from right– Elie Wiesel

Fourth from right:

• Herman Leefsma or

• Abraham Hipler or

• Berek Rosencajg or

• Zoltan Gergely

Fifth from right:

• Lajos Vartenberg (Yehuda Doron) or

• Yaakov Marton

Bottom bunk:

First from right – Max Hamburger

Third from right – Issac Reich

Fourth from right:

• Michael Miklos Nikolas Gruener or

• Gershon Blonder or

• Yosef Reich

Standing on the right: Chaim David Halberstam

Also notice that on the Flicker page the third man from left in the 2nd row up is not identified. That page went up in 2008. But on the Yad Vashem non-linkable “Anonymous No Longer” page for this particular photograph, this man is given two possible identities: Lajos Vartenburg (Yehuda Doron) or Yaakov Marton. On another Yad Vashem page with this picture, it reads:

On the second bunk from the bottom, third from left is Losh Wertenberg who later changed his name to Yehuda Doron, and according to other identification this man is Jeno Marton (identified by Yaakov Marton).

Screwy. Yad Vashem accepts whatever is sent to them because the memorial is by, for and about the Jewish people and they can do no wrong. However, we, of more discriminating nature, have to doubt that any of these names are correct … except Grüner.

Does Max Hamburger have a valid claim to be “the zombie” in the photograph?

It’s important to remember that this photo is recorded as having been taken on April 16, five days after the actual liberation. If this 4th person in the lower bunk had TB, would he still be lying in this barracks 5 days later or would he be in a hospital? If this were a hospital barracks, why do some of the men look so healthy? Elie Wiesel did not have TB, but, according to his own accounts, two days after liberation he ended up unconscious in the SS hospital with severe food poisoning. So Wiesel couldn’t be in this picture by his own statements!

Nicholas Grüner also had tuberculosis (TB) when this photo was taken. However, Grüner seems to think it was on the day of liberation, April 11, because he writes in his book Stolen Identity that as they were being marched to the camp entrance on that day (believing they were being taken somewhere to be killed), he managed to leave the line and run into the nearest barracks and jump into an empty bunk — which was this one. Later an American soldier came in and took a picture. Grüner was only 16 and had been living in the special children’s barracks, the same that Elie Wiesel says he was in. Grüner says his TB was not diagnosed until he was fully processed and he was then sent to a sanatorium in Switzerland, where he recovered.

I do not know if Max Hamburger has told a story about how his TB was treated. My information on him comes only from these few sources, mostly in the Dutch language. (Anyone who is able to translate the pdf article, please contact me.)

If Max Hamburger is the fourth man on the bottom row, he must also be the third man in the next row up (2nd row) because they are the same man. Yet he doesn’t say that — so something is very wrong with his claim.

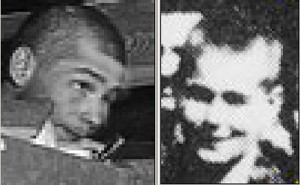

Facial comparison of the two men

After printing the largest images of the two men’s faces, I did a careful tracing of each one. I then overlaid one on the other (in the drawing above) and determined:

- The nose, eyes and eyebrows, and head lined up perfectly one with another. This would not be possible if the two faces were not the same person.

- The mouth, while also remaining identical, is shifted upward on the “zombie” (as you look at the photo) and the entire lower face is widened and the jaw squared off. I’m not sure how this was accomplished, but on this particular figure it seems to be retouching paint. Look at that cauliflower ear, for example! The head is re-situated as laying flat on the bunk board (from the original pose of being propped up a few inches), necessitating a change in the relationship to the neck.

I thickened the outline of the “original” so it’s easy to tell which is which. You can compare the small photographic images of the two faces (left: 2nd row; right: bottom row) with the overlay to see how the very poor “retouching” job was done. Talk about sloppy work!

Why not just use a different person?

Why would they decide to insert the same man and then have to go to such lengths to make him look different? I think the answer to that is: several shots of this scene (with fewer live bodies than are there now) were taken on April 16, and only later it was decided to “fill in” the empty bunks by inserting figures from other negatives. For example, the two heads on the far left in the second and third row are clearly the same man with a slightly different twist of his head. The sleeping man, second from left in the second row, may be another view of the two men on the far left! Because why isn’t he facing the camera like all the others? The standing man is also a later addition inserted onto the photograph (see here).

As I pointed out before, this “Zombie copy” was also not gauged correctly size-wise — he is noticeably smaller than the men in the bunk right above his, when they should match up according to the laws of perspective.

More on Max Hamburger

He is the son of a Dutch diamond polisher and baseball player, Hartog Hamburger. During a competition game in 1924, Hartog was hit on the head by a line drive when in the field. He died the next day as a result of the impact.

He is the son of a Dutch diamond polisher and baseball player, Hartog Hamburger. During a competition game in 1924, Hartog was hit on the head by a line drive when in the field. He died the next day as a result of the impact.

In February 2010, Max participated in the panel discussion of the Aachen Rabbi Mordechai drill in the German city of Aachen, along with the artist Máro and several others.

Both Máro (right) and his painting are shown in photo above, with Hamburger (left). According to the German news account:

“The discussion was all about the [then] 90-year-old Holocaust survivor Max Hamburger, whose speeches have gained great respect and […] the painting shown in the Castle Gallery by Máro, the image of a scene from the Buchenwald concentration camp.

“The artist explained the reasons which led him to the theme of the sufferings of Auschwitz. The series of pictures, which deals with the darkest chapter of German history, are meant to generate compassion and sensitivity for the suffering of the people depicted. […] Besides the issue of the Holocaust was also the art world itself, and the responsibility of the artist to contribute to the discussion of the Nazi terror, [which was] the focus of the [panel] discussion.”

4 Comments

Category Featured | Tags: Tags: artist Máro, Auschwitz, Buchenwald liberation photo, Elie Wiesel, Max Hamburger, Nicholas Gruner, Yad Vashem Memorial Museum, Yehuda Doron,

Social Networks: Facebook, Twitter, Google Bookmarks, del.icio.us, StumbleUpon, Digg, Reddit, Posterous.

Max Hamburger in 2012 pointing to himself in the Famous Buchenwald Lie-beration Photo from 1945 (Source: Aanspraak magazine)

Max Hamburger in 2012 pointing to himself in the Famous Buchenwald Lie-beration Photo from 1945 (Source: Aanspraak magazine)