Thursday, January 7th, 2016

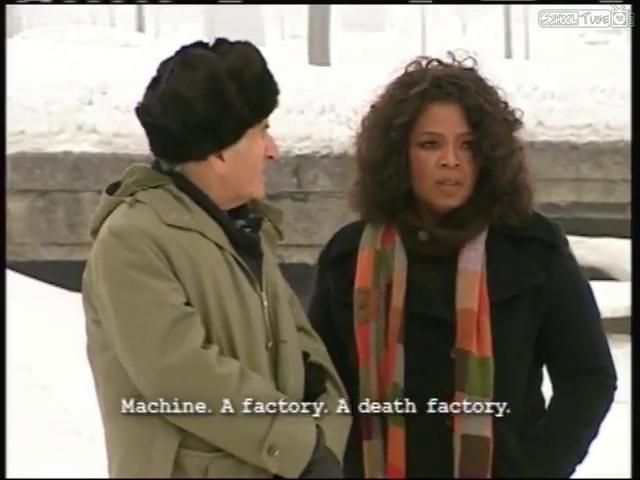

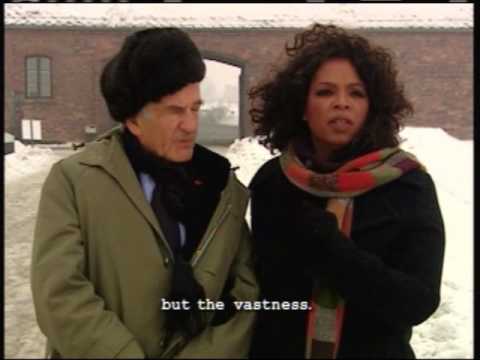

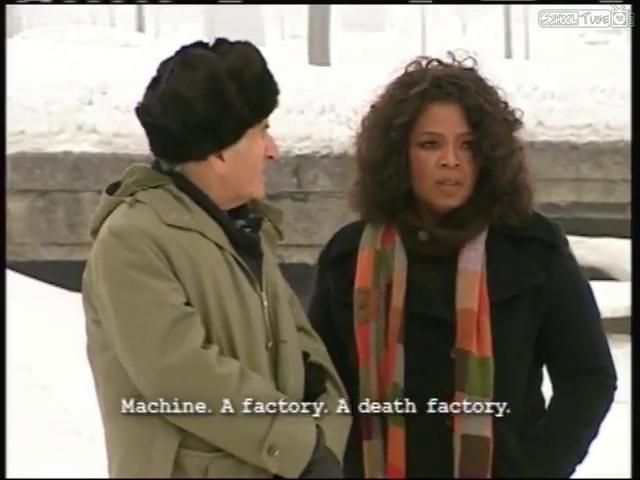

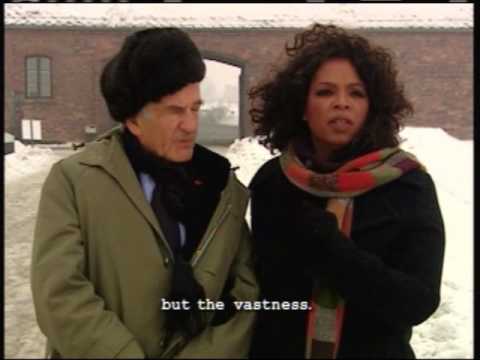

Elie and Oprah star in a very boring film about … walking around in the snow. Here they are in front of the Auschwitz 1 crematorium, feeling the horror.

By Carolyn Yeager

The Germans have been accused of making soap from jewish corpses in Auschwitz , but it takes a jew to make a soap opera there.

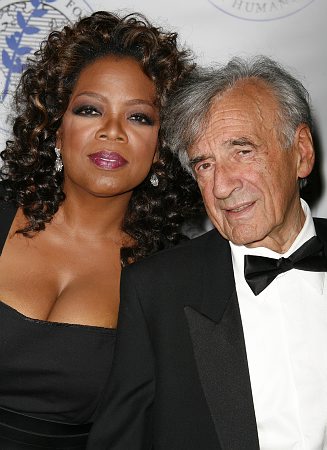

Victim Elie Wiesel and victim enabler Oprah Winfrey made a soap opera at Auschwitz on January 29, 2006, exactly ten years ago. The two superstars, along with Winfrey’s film crew, met in front of the entrance to Birkenau and much of that filming was added to the documentary created later in-studio by Oprah’s production team. The resulting 45-minute “movie” was broadcast as part of The Oprah Winfrey Show in May of that year.

Recall it was thirteen days earlier on Jan. 16 that Winfrey announced the “new 2006 translation” of Elie Wiesel’s Night as her newest book club selection. The next day, Jan. 17, Amazon announced it was changing the category of Night from novel to memoir. A lot of questions were raised (as it was known they would be), and the Elie-Oprah Auschwitz trip was intended to distract attention away from those embarrassing questions … to reinforce to the public that Wiesel was a genuine, suffering “death camp”survivor and Night was unquestionably his true story.

It was, in my opinion, a business venture that the advisers to both parties worked out as part of the entire deal between Oprah and Elie. All that the two headliners had to do was show up and act out the roles they knew so well. Oprah has referred to Wiesel as “my world hero” and said she was never the same after reading Night; she was the perfect gullible, unquestioning foil for him.

It was assumed by Oprah and the manipulated public that Wiesel would be her guide to a place he knew well. (And it would have been a perfect time for him to show his tattoo to the camera … if he had one.) But as I will point out, Elie’s words, or lack of them, expose him as a stranger to that place. He tells fiction after fiction, taken from lurid survivor testimonies that were discredited long ago. The only things he really describes are his emotions, his feelings, his thoughts … which become boring and are not convincing either.

In the film @3:43, Elie says, “Each time I come, I – I try not to speak for a day or two or three … ” but from what I can discover, this was only the 3rd time Wiesel had been there. The first was on Janurary 27, 1995, when he spoke at the 50th anniversary of the so-called liberation of the Auschwitz-Birkenau camp. It was probably on this same trip that he filmed a documentary beginning in summer 1994, both in Sighet, Romania and in Auschwitz-Birkenau in Poland. In that film, “Elie Wiesel Goes Home,” he is shown silently walking around the Birkenau grounds with his shirtsleeves rolled up, revealing bare arms with no sign of the tattoo A7713 he says he still has. (He said this as late as 2010.)

This 3rd and last time he made the film with Oprah, which was titled “Auschwitz Death Camp“. The lies and just plain ignorance that are packed into this program is amazing. I will refute some of it here. Elie actually says very little in the beginning but reads passages from Night in order to not speak such stupidities on camera. It is understood by most reasonably sophisticated people that Night is a creative effort—not to be taken literally. Notice that in the film he doesn’t describe his life in the camp with any detail–no names, specific persons, places, events—only generalizations anyone could come up with. For instance, standing in front of Block 17 in Auschwitz 1, where he says he lived, he claims he thinks often about those who died there, but doesn’t offer a single name or how they died.

Oprah takes in every word from the “Professor” (as she calls him) as profound, and though she responds in her trademark super-sympathetic manner, it does seem that she would have liked something more solid from him. She seemed to me to find her hero’s wandering, empty thoughts unsettling – and was pretty much left speechless. This has to be why her production team added so many background film clips and photos portraying the usual media version of the holocaust story—to add some content to a boring walk in the snow with an old con man. Sorry, but if you pay close attention, you should come to the same conclusion.

The main errors refuted

I link to the pages on Oprah.com that I am commenting on, and highlight the offending passages in boldface, so that you can follow and compare.

http://www.oprah.com/world/Inside-Auschwitz/1

As young Elie Wiesel stepped off the cattle car at the Auschwitz subcamp Birkenau, also known as Auschwitz II, he smelled the stench of burning human flesh and saw the crematorium throwing its flames into the sky. “[Mrs. Schächter] wasn’t so mad at all,” Oprah says. “She was a prophet.”

Oprah shows exceptional ignorance by believing that flames could be coming out of a crematorium chimney, but this is what was written in Night. She even believes in Mrs. Schacter, who is simply a character Wiesel invented.1

There was no stench of burning flesh in the air at Birkenau, in spite of quite a number of “survivor novels” that say so. Operating crematoria do not release any smell. Wiesel picked up that idea of “stench” from the testimonies at the Nuremberg tribunal and Soviet reports. In 1955 he thought it was safe to say such things. Today we know what he wrote did not happen.

http://www.oprah.com/world/Inside-Auschwitz/2

The systematic process of determining who would live and who would die was known as “selection.” SS officers briefly sized up each new arrival. Those deemed capable of hard labor, like 15-year-old Elie Wiesel and his father, went into the work camp. All others were sent immediately and unknowingly down the path to Auschwitz’s four gas chambers.

The “selection” was for work placement, not life or death. Those who could not work (children, elderly and sick) went into the barracks at Birkenau where they were fed and allowed to join in activities. There was actually a lot going on. Mail was delivered in both directions, packages were received, the health clinics and hospitals were busy. Some did light work in the camp. Even babies were born.

No one went to a gas chamber because there were none. Wiesel never, ever spoke of a gas chamber in his book Night, written in 1954, and further edited from 1956-58. He only spoke of people taken to the crematorium after they died, which to him at that time was only from disease, hard work and mistreatment—not gas chambers!

West London Crematorium, 2005

Those selected to die were told they were getting showers, then packed into the chambers by the thousands. Canisters of the deadly chemical Zyklon B were dropped in. As the toxic pellets mixed with air, cyanide gas was released. Death took about 15 minutes to come and felt like suffocation. Proud of their efficiency, SS officers witnessed the gassing as it happened through special peepholes.

None of this is true. Shower facilities were real showers, an important part of the camp disease prevention program.

“Canisters of Zyklon B were dropped in”? What would canisters do? Does Oprah expect that the ‘victims’ opened the canisters themselves?

Death from Zyklon B poisoning would not feel like suffocation. Death by poison gas is painless; one just drifts into unconsciousness.

Claiming that SS officers watched people die through peepholes is the lowest form of defamation of Germans—one thing that Wiesel specializes in. He is pawning off this gruesome “camp gossip” to Oprah and she is not questioning it. But later in the video she did keep saying she “couldn’t understand” how human beings could do such things. The answer is they didn’t.

The grisly task of burning the dead bodies in underground ovens was left to Jewish prisoners. Forced into this horrific job, they temporarily evaded their own death.

What is meant by “underground ovens”? There was no such thing. There were above-ground crematoria for hygienic disposal of human corpses, exactly the same as are found all over the world. There is nothing sinister about cremation retorts. Oven is a word meant to mislead people by bringing up images from the fairy tale “Hansel and Gretel!”

It doesn’t say much for jews if they agreed to kill and cremate their own people just to put off their own death for a short time. There is no way to force someone to do this. This is one of the weakest links in the Jewish Holocaust narrative.

http://www.oprah.com/world/Inside-Auschwitz/3

Professor Wiesel takes Oprah inside one of the few barracks still standing at Auschwitz. He says that prisoners were packed two or more to a bunk on straw mattresses. Professor Wiesel slept on similar bunks at Auschwitz and later at Buchenwald.

Wiesel never wrote of sleeping two (or more) to a bunk. He wrote that at times he was on the top bunk and his father on the bottom. In Buchenwald there was never two to a mattress, especially in the children’s barrack.

Most people don’t find straw mattresses unpleasant to sleep on, especially if they’re tired enough, but most of the people living in Birkenau actually didn’t do much in the way of work and exercise.

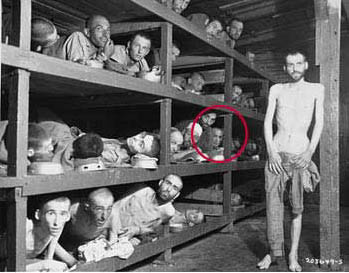

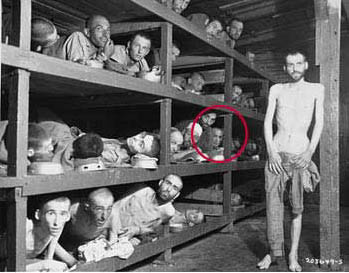

“Elie Wiesel looks out from the far right of the middle bunk.” This photo was staged in an empty barrack because the mattresses have already been removed, 5 days after liberation.

In this photo, taken by soldiers on April 16, 1945, after the liberation of Buchewald, Elie Wiesel looks out from the far right of the middle bunk.

That is not Elie Wiesel in the photo. That person looks nothing like him, but also he writes in his various memoirs that he became seriously ill with food poisoning two days after the April 11th liberation and was taken to a hospital where he stayed for two weeks. Think how ludicrous it is that he should claim to be in both places at the same time! This should tell you something about Wiesel’s irresponsibility when it comes to the holocaust narrative. Anything goes.

Rats, lice and other vermin were rampant. Deadly outbreaks of dysentery, typhus, tuberculosis and malaria wiped out entire sections of this camp. Inmates wore thin cotton uniforms year round, even in the harshest winter. Given only meager rations of stale bread and meatless soup, many starved to death. For prisoners not sentenced to die in the gas chambers, the average life span was barely four months.

Complete nonsense. The barracks at Birkenau were cleaned and disinfected regularly. Wiesel even writes about it in Night.

There are photographs of outdoor workers wearing heavy coats, boots, caps and gloves in winter.

NO ONE STARVED TO DEATH. The emaciated inmates at the end of the war were afflicted with wasting diseases, not starvation.

That the life span was 4 months is an invention picked up by Elie Wiesel from other “survivor stories.” Why then are there millions who were in the camps for several years and are now still getting a reparation check every month?

For saying these kinds of irresponsible things, Wiesel should be reprimanded by the Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial staff, but he isn’t.

http://www.oprah.com/world/Inside-Auschwitz/7

At Auschwitz 1, the notorious Dr. Josef Mengele, known as the Angel of Death, conducted sadistic medical experiments on prisoners, infecting them with diseases, rubbing chemicals into their skin and performing crude sterilization experiments in his quest to eliminate the Jewish race by any means possible.

Dr. Mengele was a normal man who served humanity as a doctor.

All the stories about Mengele are inventions. True, he was interested in gaining knowledge about certain medical conditions but not in the way the crazy, narcissistic jews talk about it. He was actually a goodhearted man who has been made into a devil. Elie Wiesel never laid eyes on him anyway.

In Block 11, the secret German police, the Gestapo, interrogated and tortured political prisoners and anyone who dared to disobey.

The Gestapo had an office at Auschwitz. There was a good deal of sabotage and contact with the enemy carried out by Auschwitz 1, 2 and 3 inmates, especially the Poles who had a strong network with Warsaw and London. This could not be allowed and was punished severely. But the Gestapo didn’t regularly “torture political prisoners” or those who “dared to disobey.” That is more camp gossip. Good police know how to gather evidence and get confessions without torturing people. Block 11 was simply the camp jail and it has has been built up into a torture chamber, which it wasn’t.

“At least they had individual deaths—even this becomes a privilege,” Professor Wiesel says. “Here, actually, death was a release because it followed the torture.”

What’s he talking about? Nothing, it’s Wiesel-speak. We can’t know what he means by “torture” since everything is a torture for him. But he pushes the theme that death was preferable to life in the camps—at the same time he describes how he and everyone else clung to life. He preaches that the camps were places of continual punishment, which isn’t the reality at all. If it were, how would so many millions have come out at the end of the war in good health?

http://www.oprah.com/world/Inside-Auschwitz/8

A case filled with empty Zyklon B cans is a haunting reminder of the poisonous gas used by the Nazis for killing prisoners on a massive scale. “When the gas chambers were full, an SS man put on the gas mask, went to the roof, opened the little window there and threw such a can into the gas chamber,” Professor Wiesel explains. “Unspeakable pain and horror—that’s how they were killed. Mothers and children hugging.

Once again, the claim of mass killing is false. Prisoners were kept as healthy as possible in order to be able to work. And also once again, they’re throwing cans into the “gas chamber” through a little window in the roof. Pretty stupid of the SS men!

Also – once again – death by Zykon gas is painless.

“Mothers and children hugging” is pure soap opera fiction to effect the emotions of school kids and women like Oprah. It has been shown conclusively that there never were any homicidal gas chambers. It was black ops propaganda and is now just a plain old Big Lie.

http://www.oprah.com/world/Inside-Auschwitz/10

Baby clothes and shoes are all that remain of the death camp’s smallest victims. Infants were killed immediately on arrival, as were the young mothers who refused to leave their children.

No evidence for that at all. A few items of baby clothes is sure not evidence. The evidence shows that children were provided with kindergartens at Birkenau with painted murals on the wall. Babies were born at the hospital at Auschwitz. I could go on and on.

Wiesel is on overdrive to make Nazis guilty of unspeakable crimes … the better to extort billions from Germany for Israel.

In a short promo video, Oprah says to Elie “You saw the babies thrown into the fire” while an image of cremation “ovens” is shown on the screen. This is purposely misleading because Elie was speaking of babies thrown into open pit fires—but no one will believe that anymore. Wiesel won’t give up his “jewish-babies-burned-alive-in-fire” narrative because fire is part of the Jewish redemption narrative and it is the most evil curse he can put on the hated “Nazis.”

http://www.oprah.com/world/Inside-Auschwitz/12

The Nazis went to sinister lengths to profit from the extermination of millions, and no possible resource was wasted. Human hair shorn from victims’ scalps was gathered and sold to German factories to make cloth.

Human hair was cut short to control body lice that the jews and others brought with them to the camp–not to make a profit. They no doubt couldn’t have profited, considering all the barbers that were necessary. It was a life-saving measure.

What was done with the hair after it was cut was of no importance to the inmates. Do you want to keep the hair that is cut from your head? Do you worry that the salon or barber shop will make a profit from it? I doubt it. Wiesel tries to connect cutting of hair with extermination, but there is no connection. Failing that, he projects it as a humiliation.

Wiesel wants you to believe that the “Nazis” made money off the jews’ bodies by selling their hair, when in fact they were just making use of all resources in their wartime economy. Is it better to throw stuff away, or to recycle it?

Final thoughts

We could ask why Elie didn’t take Oprah to see the swimming pool. Or take her into one of the large kitchens, or the theatre. Or point out where the soccer field had been in Birkenau. Apart from the fact that he may not even know about this places, since he never lived there, both knew that bringing up that aspect of the camps would defeat the purpose and soapiness of their soap opera. Their purpose was to reinforce the stature of Elie Wiesel and his book Night, and a secondary benefit was to give Oprah more tear-jerking content for her TV show. In May 2011 Night was #3 on the Top Ten bestseller list from the Oprah Book Clubs in their final 10 years, according to Nielsen BookScan.

Winfrey did her best as an actress even though she broke character in a couple places, halting expressing her confusion about the story, saying she couldn’t make any sense of it. Wiesel immediately counseled her that she should not look for sense because none could be made of it. It is unexplainable and inexplicable … and a permanent mystery. As for upholding his part in making the film interesting, Wiesel totally failed. He was a bore. His Auschwitz experience remains preposterous and unconvincing—really just a soap opera.

Endnotes:

- Wiesel said in an interview with the Paris Review in 1984:

Sighet, my little town, all the characters that I am inventing or reinventing, all the tunes that I have heard. It is always, whatever its name, that little town Sighet.

The real Sighet was actually the largest city in Maramures province with a population of 50,000 to 90,000 people, and was 35 to 50% Jewish … as written by Wiesel himself in Un di velt hot geshvign, the Yiddish precursor to Night. But in Wiesel’s other books, Sighet is a product of his imagination.

3 Comments

Category Featured | Tags: Tags: Auschwitz-Birkenau, crematoria, Jewish Soap, Night, Oprah Winfrey, Soap opera, Zyklon B,

Social Networks: Facebook, Twitter, Google Bookmarks, del.icio.us, StumbleUpon, Digg, Reddit, Posterous.

Friday, February 17th, 2012

By Carolyn Yeager

copyright 2012 Carolyn Yeager

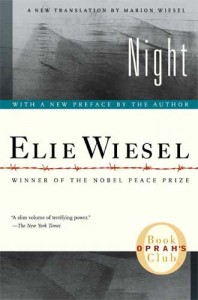

On Tuesday, January 17, 2006, Amazon.com announced that it was changing the categorization of a new translation of Elie Wiesel’s Night from novel to memoir.

Amazon would also revise the editorial description of the original edition to make clear that they consider the book a memoir, not a novel. “We hope to make these changes as quickly as possible,” said Jani Strand, a spokeswoman for the online retailer. The day before, Oprah Winfrey had announced that Night was her latest book club choice, displacing her previous selection, James Frey’s A Million Little Pieces.

The sudden switch from fiction to non-fiction caused some discussion and questions, which Strand brushed away by saying, “Amazon.com’s data source for the Oprah Book Club edition of Night inaccurately classified the book as fiction.” She declined to offer details. The book, re-classified as “Autobiography” and blessed by Oprah, was already No.3 on Amazon.com as of that Tuesday afternoon! Wiesel, interviewed later with his literary agent Georges Borchardt, insisted they had never portrayed it as a novel.

The sudden switch from fiction to non-fiction caused some discussion and questions, which Strand brushed away by saying, “Amazon.com’s data source for the Oprah Book Club edition of Night inaccurately classified the book as fiction.” She declined to offer details. The book, re-classified as “Autobiography” and blessed by Oprah, was already No.3 on Amazon.com as of that Tuesday afternoon! Wiesel, interviewed later with his literary agent Georges Borchardt, insisted they had never portrayed it as a novel.

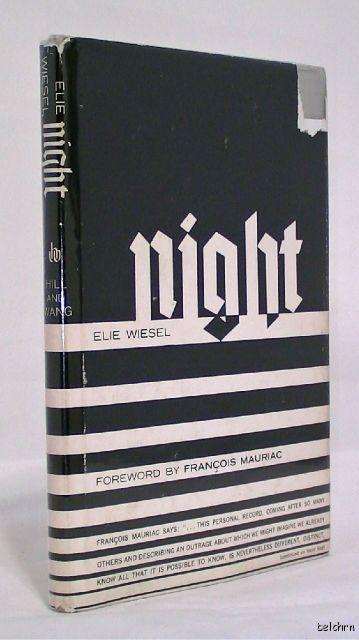

But the publisher did.1 There has been confusion about the question for so long—even Wiesel’s defenders have to admit it. Ruth Franklin, in her 2011 book, A Thousand Darknesses, wrote: “Unfortunately, Night is an imperfect ambassador for the infallibility of the memoir, owing to the fact that it has been treated very often as a novel—by journalists, by scholars, and even by its publishers.”2 On Night’s Wikipedia page it has long been described as autobiography, memoir, novel—yes, all three. How long will that continue? As long as there are editions of Night that still sport those labels, one assumes.

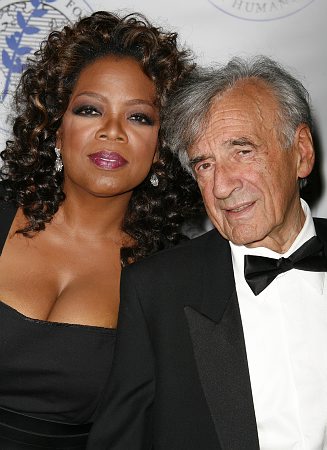

Left: Oprah Winfrey and Elie Wiesel pose together at the Elie Wiesel Foundation for Humanity Award Dinner at the Waldorf Astoria Hotel on May 20, 2007. Winfrey was honored with the Humanitarian Award for “positively impacting people all over the world, especially children.” One year earlier, she had selected Wiesel’s “Night” for her popular book club “pick” which sent it immediately to the top of the national bestseller lists.

As for Wiesel and Borchardt, they answered questions about differences in the text of the new edition by saying they were not significant enough to justify raising questions. The next day, Wiesel’s wife Marion, the translator of the new edition of Night, said in an interview that among the changes was a reference to the age of the book’s narrator when he arrives in 1944 at Birkenau, the entry point for Auschwitz.

“At no point did this change the meaning and the fact of anything in the book,” Marion Wiesel said. She explained it this way: The narrator tells a fellow prisoner that he is “not quite 15.” But the scene takes place in Spring 1944. Mr. Wiesel, born on Sept. 30, 1928, would have already been 15, going on 16. So in the new edition, she changed it to “15.” Whaaaa? She changed the age of Eliezer as it was written in the Yiddish book to fit Elie Wiesel, who was fifteen and a half at that time. What is written in the Yiddish original, Un di velt hot geshvign, we also find in the original Night, so that can only be called unethical. Marion tried to joke it away, telling reporters “I kidded Elie and told him, ‘I don’t think you can add.'”

“At no point did this change the meaning and the fact of anything in the book,” Marion Wiesel said. She explained it this way: The narrator tells a fellow prisoner that he is “not quite 15.” But the scene takes place in Spring 1944. Mr. Wiesel, born on Sept. 30, 1928, would have already been 15, going on 16. So in the new edition, she changed it to “15.” Whaaaa? She changed the age of Eliezer as it was written in the Yiddish book to fit Elie Wiesel, who was fifteen and a half at that time. What is written in the Yiddish original, Un di velt hot geshvign, we also find in the original Night, so that can only be called unethical. Marion tried to joke it away, telling reporters “I kidded Elie and told him, ‘I don’t think you can add.'”

But that particular change, rather than insignificant, was one of the major reasons that a new translation was undertaken. There are other quite significant changes in the new edition that will be enumerated in this article. When you learn what they are, you can decide for yourself if you think they are insignificant.

Right: Marion Wiesel is the translator of the 2006 edition of Night. Here, in 2010, she attends an after party at The Monkey Bar for Oliver Stone’s new “South of the Border” New York premiere at Cinema 21.

Wiesel wrote a Preface to the New Translation, something he didn’t have in the original La Nuit or Night.

In his preface, Wiesel begins: “Why did I write it? … so as not to go mad or, on the contrary, to go mad in order to understand the nature of madness …”

He continues in this vein—typical Wiesel mystical-religious style. However, in his only description of the writing process of this book—the typing of the 862 pages which he titled Un di velt hot geshvign, according to his later memoir—it is hard to believe that he was in such a state of mind. He writes in All Rivers Run to the Sea that during this time in Paris he is busy with his newspaper job and contacts; also involved in a love affair with a woman named Hanna. He embarks on a major journalistic assignment in Brazil, sent by his editor, taking along a friend to keep him company on the ship’s crossing. They both get free tickets from a “resourceful Israeli friend”—these benefactors are usually unnamed. As the voyage begins, he says his mind is dwelling on Hanna and whether he should take the marriage step that she had asked for.

I can’t imagine an atmosphere less conducive to writing about what he describes as “the immense, terrifying madness that had erupted in history.” But he continues very matter-of-factly in All Rivers, “During the crossing I wrote my testimony …” and in one short paragraph tells us all he thought important to say about it. Moreover, he has never elaborated on it since!

In the new preface, Wiesel writes that in retrospect he doesn’t know what he wanted to achieve with his words, but then he comes up with something: “I knew that I must bear witness. I also knew that, while I had many things to say, I did not have the words to say them.” He needed to “invent a new language.” He is not speaking of an actual language, like German, French or English—but a language of survivors, or for survivors. Wiesel writes that common words like “hunger—thirst—fear—transport—selection—fire—chimney … all have intrinsic meaning, but in those times, they meant something else.” Really? He does not explain how that is so. But Wiesel has tried to create the idea of holocaust survivors as a special class, set apart, who know things others do not know, and can never understand—”Only those who experienced Auschwitz know what it was. Others will never know.”

Wiesel describes his writing as slow! “Writing in my mother tongue (Yiddish) … I would pause at every sentence, and start over and over again. I would conjure up other verbs, other images, other silent cries. It still was not right.” This contrasts totally with his description in his memoir All Rivers Run to the Sea (p. 238-40) that he wrote the original Yiddish manuscript fast and feverishly without re-reading!

Why a new translation of Night after 45 years of success with the old one?

Here again, Wiesel hedges in the preface and doesn’t have a convincing answer. He says his wife Marion has translated other books for him, and “knows his voice better than anyone else.” He says he didn’t pay enough attention to the original English translation by Stella Rodway—after his first reading of Night from the publisher, he never read it again. As for Mrs. Wiesel: “Fluent in French, she had never read the English version,” she said. But good news! Elie Wiesel Cons The World has found a translator and now has large portions of the Yiddish book translated into English. We can compare the real 245-page original to both the 1960 English translation from the French by Stella Rodway and the 2006 English translation done by Marion Wiesel.

In doing so, we have made two important discoveries.

First, Stella Rodway’s 1960 English translation of Night is an accurate rendition of the French text of La Nuit, as originally published in 1958. That means that if there are any “errors” in the Night story, they weren’t put there by Stella Rodway.

Second, when we compare the three texts—the original version of Night, as translated by Rodway, the “corrected” 2006 translation by Marion Wiesel, and the 1955 Yiddish original of Un di velt hot geshvign—we find that the “errors” brought up by Marion Wiesel are for the greater part what was actually written in the original Yiddish book, though usually in more detail there.

In other words, the 1955 Yiddish version, the 1958 French version, and the 1960 English version generally agree—only the “corrected” 2006 translation is different. So, are these really errors of translation that Marion Wiesel is fixing for us? Or are they not simply problems for Elie Wiesel? Under close scrutiny, the Elie Wiesel narrative has huge holes which bring up embarrassing questions, and this is what Marion Wiesel’s new translation was meant to head off.

Left: Original Night cover, 1960, features the title, while the author’s name is exceptionally small and insignificant. Francois Mauriac’s forward is featured. In 2006, the author becomes the “title,” i.e. the main selling point, and Mauriac is no longer mentioned, although his forward remains in the book.

A Comparison of the 1960 original with the 2006 new version.

Following are the most “significant” differences I have found between the Stella Rodway 1960 translation and the Marion Wiesel 2006 translation. To make as clear a case as possible, I begin with the Yiddish [UdV] and its French translation La Nuit [LN], followed by the Stella Rodway English translation [SR]. Finally, Marion Wiesel’s revised translation [MW]. The word or phrase being compared is in boldface. Number one has already been written about in When Did Elie Wiesel Arrive at Auschwitz?

1. The Saturday before Pentecost … or two weeks before?

UdV Page 22: Geshen iz dos Shbth far Shbw’wth. A friling-zun hot oysgegosn ir likht un varemkeyt iber der gorer velt un oykh iber geto … / It happened Saturday [Sabbath] before Shavuot. The springtime sun had spread its light and warmth over the whole world, and even over the ghetto. . . .

LN Page 29: Le samedi précédant la Pentecôte, sous un soleil printanier, les gens se promenaient insouciants à travers les rues grouillantes de monde / The Saturday preceding Pentecost …

SR Page 23: On the Saturday before Pentecost, in the Spring sunshine, people strolled carefree and unheeding, through the swarming streets.

MW Page 12: Some two weeks before Shavuot (Pentecost). A sunny spring day, people strolled seemingly carefree through the crowded streets.

The Yiddish, the French and the original English versions agree—it was the Saturday before the festival of Pentecost/Shavuot—but Marion Wiesel’s new edition sets that date back by two whole weeks. This is very significant because, as the story continues, it was later on the following day that the Jews of Sighet were forced to leave their homes in preparation for their eventual deportation: “The ghetto was to be liquidated entirely. We were to leave street by street, starting the following day.”

So Mrs.Wiesel was NOT correcting errors in the English translation, but changing the text to fit the reality of when the Hungarians from Sighet arrived at Birkenau. Pentecost was on Sunday, May 28, 1944. The “Saturday before Pentecost” is thus May 27. Some two weeks before is May 14.

Un di velt hot geshvign, La Nuit and the Rodway translation all have Eliezer’s family leaving on the final journey to Auschwitz around June 2nd, six days after Pentecost/Shavuot, which was a Friday. However, they also agree that “Saturday, the day of rest, was chosen for our expulsion.” So it’s necessary for us to add another day to the family’s stay in the small ghetto to make the chronology work. On Saturday, then, the Jews are marched to the synagogue and spend the night there; in the morning, Sunday June 4, they board the train: “The following morning [Sunday], we marched to the station, where a convoy of cattle wagons was waiting. [… ] We were on our way.” Four days and three nights on the train (according to the description in Night) makes their arrival date June 6, 1944, around midnight.

But this is not only long after the prisoner number A7713—which Elie Wiesel supposedly received at Auschwitz, and still (again, supposedly!) has tattooed on his left arm—had been given out, but also long after the last transport left from Sighet. Indeed, there were no transports from the town after May, according to official records.

Marion Wiesel did not mention this one to the reporters; nor did Elie speak of it in his preface to his wife’s translation. But it was discovered by our translator. Marion Wiesel’s arbitrary “correction” allows Eliezer’s family to leave on May 21 and to arrive by May 24 (just before midnight!) thus making it possible for Eliezer to receive the registration number A7713. This is a very significant change, probably the most significant in her entire new English translation.

An added note: This interesting passage is on page 27 of Un di velt, but is not included in the shorter French or English Night:

We had opportunities and possibilities to hide with regular goyim and with prominent personalities. Many non-Jews from the surrounding villages had begged us, that we would come to them. There were bunkers available for us in villages or in the mountains. But we had cast aside all proposals. Why? Quite simple: the calendar showed April 1944 and we, the Jews of Sighet, still knew nothing about Treblinka, Buchenwald and Auschwitz.

Now we have April as the general time of deportation! So according to the timeline we find in Un di velt, Eliezer and his family left Sighet some time in June, while the calendar on their wall still said April . . . and in the meantime, we know from official Auschwitz records that the deportations actually occurred in the last two weeks of May. The person who wrote this knew nothing about the real deportation dates for the Sighet Jews.

2. Copulating on the train … or just caressing?

UdV Page 47: Tsulib der engshaft hobn a sakh instinktn zikh dervekt in kerper. Erotishe instinktn, un untern forhang fun der nakht hobn yungeleyt un froyen zikh gelozn bahersht durkh di oyfgereytste chwshym zeyere.

Ot der ershter rezultat fun umglik: erotishe freyheyt. Di shpanung fun di letste teg hot itst gezukht a veg vi oystsulodn zikh un der leychtster iz geven – an erotisher.

Di erotishe stsenes hobn nisht dervekt keyn protestn mtsd di eltere Yidn. Zey hobn farmakht oyern un oygn, zikh gemakht nisht zen un nisht hern. In moment fun schnh faln avek di keytn fun der konventsioneler moral. Mentshn hobn zikh getrakht: ver veys vos der morgn iz “lwl tsu brengen? Zol yugnt oysnutsn dem heynt, oystsapn fun im dem letstn hn’h-tropn . . .

In English: Because of the crowding, a host of instincts awoke in [people’s] bodies. Erotic instincts – and beneath the curtain of night young men and women let themselves be ruled by their aroused senses.

And so the first result of misfortune: erotic freedom. The stress of the last days now sought a way to discharge itself, and the easiest was – an erotic one.

The erotic scenes did not arouse any protests from the older Jews. They closed their ears and eyes, and forced themselves not to see and hear. In the moment of danger, the chains of conventional morality fall away. People thought to themselves: who knows what the morning is likely to bring? Youth must seize the day, squeeze from it the last drops of pleasure . . .

LN Page 45: Libérés de toute censure sociale, les jeunes se laissaient aller ouvertement à leurs instincts et à la faveur de la nuit, s’accouplaient au milieu de nous, sans se préoccuper de qui que ce fût, seuls dans le monde. Les autres faisaient semblant de ne rien voir.

SR Page 34: “Free from all social constraint, the young people gave way openly to instinct, taking advantage of the darkness to copulate in our midst, without caring about anyone else, as though they were alone in the world. The rest pretended not to notice anything.”

MW Page 23: “Freed of normal constraints, some of the young let go of their inhibitions and, under cover of darkness, caressed one another, without any thought of others, alone in the world. The others pretended not to notice.”

Elie Wiesel did not mention this change in his preface to the new English translation by his wife, but he did give quite a lengthy explanation (humorous to us) in the preface he wrote for the new French edition. This is what he said there:

Thanks to her, it was possible for me to correct an incorrect expression or impression here and there. An example: I describe the first night-time voyage in the sealed cars, and I mention that certain persons had taken advantage of the darkness to commit sexual acts. That’s false. In the Yiddish text, I say that “young boys and girls allowed themselves to be mastered by their excited erotic instincts.” I have checked among many absolutely trustworthy sources. In the train, all the families were still together. A few weeks of the ghetto could not have degraded our behavior to the point of violating customs, mores and ancient laws. That there may have been some clumsy touching, that is possible. But that was all. Nothing went any further. But then, why did I say that in Yiddish, and allow it to be translated into French and English? The only possible explanation: it is myself I am speaking of. It is myself that I condemn. I imagine that the adolescent that I was then, in the throes of puberty even if profoundly pious, could not resist such erotic imaginings, enriched by the physical proximity between men and women.

The original French : Grâce à elle, il me fut permis de corriger çà et là une expression ou une impression erronées. Exemple : j’évoque le premier voyage nocturne dans les wagons plombés et je mentionne que certaines personnes avaient profité de l’obscurité pour commettre des actes sexuels. C’est faux. Dans le texte yiddish je dis que « des jeunes garçons et filles se sont laissés maîtriser par leurs instincts érotiques excités. » J’ai vérifié auprès de plusieurs sources absolument sûres. Dans le train toutes les familles étaient encore réunies. Quelques semaines de ghetto n’ont pas pu dégrader notre comportement au point de violer coutumes, moeurs et lois anciennes. Qu’il y ait eu des attouchements maladroits, c’est possible. Ce fut tout. Nul n’est allé plus loin. Mais alors, pourquoi l’ai-je dit en yiddish et permis de le traduire en français et en anglais? La seule explication possible: c’est de moi-même que je parle. C’est moi-même que je condamne. J’imagine que l’adolescent que j’étais, en pleine puberté bien que profondément pieux, ne pouvait résister à l’imaginaire érotique enrichi par la proximité physique entre hommes et femmes.

Is this convincing, dear readers? Consider that the narrator of Un di velt says exactly the opposite of what Wiesel tries to present in his new French preface: the first result of a few weeks in the ghetto was erotic freedom, which was acted out in front of everyone in the train. And the “erotic instincts” that the youths let themselves be “ruled by” clearly must have involved sexual intercourse—why else would everyone have needed to shut their eyes and ears so tightly?

Liar Ruth Franklin

The Elie Wiesel of 2006 (and perhaps the Hasidic rebbes had something to do with this?) wants us to believe in the inviolable sanctity of the Jews’ “customs, mores and ancient laws,” and also in their innate respect for their elders and one another. But he is directly contradicted by what are, we are told, his own words of fifty years ago : “In the moment of danger, the chains of conventional morality fall away.” Which Wiesel do we believe?

And Ruth Franklin, senior editor at The New Republic, has the temerity to insist (toward the end of her 2006 review article) that “his [Elie’s] original suggestion that couples “copulated” in the cattle cars on the way to Auschwitz . . . was always a gross mistranslation of the original Yiddish.” We’ve shown you here that it isn’t.

3. Not yet fifteen … or fifteen?

UdV Page 63 : Yingl, vi alt bistu? fregt mir a heftling. Zeyn pnym iz geven in der fintster, ober zeyn kol iz geven a mids, a varems. Nokh nisht keyn 15 yor, hob ikh geentfert.

“Kid, how old are you?” a prisoner asked me. His face was in darkness, but his voice was tired and warm. “Not yet 15 years,” I answered.

LN Page 54: Hé, le gosse, quel âge as-tu? C’était un détenu qui m’interrogeait. Je ne voyais pas son visage, mais sa voix était lasse et chaude. “Pas encore quinze ans.” / Not yet 15 years.

SR Page 39: “Here, kid, how old are you?” It was one of the prisoners who asked me this. I could not see his face, but his voice was tense and weary. “I’m not quite fifteen yet.”

MW Page 30: “Hey, kid, how old are you?” The man interrogating me was an inmate. I could not see his face, but his voice was weary and warm. “Fifteen”

This very important passage was discussed above. I think the reader would agree that “not yet 15″ can mean even farther from the age of 15 than “not quite fifteen.” What is clear is that Marion Wiesel has changed the author’s original words to fit them to her husband’s age in Spring 1944.

4. April … or May?

UdV Page 83: A sheyner April-tog iz es geven. A frilings-rich in der luft. In English: It was a beautiful April day. A scent of spring in the air.

LN Page 69: C’était une belle journee d’avril. Des parfums de printemps flottaient dans l’air. Le soleil baissait vers l’ouest.

SR Page 49: It was a beautiful April day. The fragrance of spring was in the air. The sun was setting in the west.

MW Page 40: It was a beautiful day in May. The fragrances of spring were in the air. The sun was setting.

(See again When Did Wiesel Arrive) Once more, the original Night as translated by Stella Rodway agrees with the Yiddish and the French; Marion Wiesel arbitrarily changed April to May, yet said her translation did not “change the meaning or the fact of anything in the book” … what she calls a “significant change.” Well, this is a significant change, and for the same reason as given in number 1 above.

5. Himmler … or “Reichsfuehrer Himmler?”

UdV Page 124-5: “In nomen fun Himler . . . der heftling num’ . . . hot gegnbet . . . bsh”thn luft-alarm . . . loytn gezets, paragraf . . . iz der heftling num’ . . . farurteylt tsum toyt! Zol dos zeyn a lere un a beyshpil far ale heftlingen . . .”

“In the name of Himmler . . . prisoner number . . . stole . . . during the air raid . . . according to the law, paragraph . . . prisoner number . . . is condemned to death. May this be a lesson and an example for all prisoners.”

LN Page 100: “Au nom de Himmler ... Le détenu No… a dérobé pendant l’alerte… “

SR Page 68: “In the name of Himmler … prisoner Number … stole during the alert … According to the law … paragraph …prisoner Number … is condemned to death. May this be a warning and an example to all prisoners.”

MW Page 62: “In the name of Reichsfuehrer Himmler … prisoner number … stole during the air raid … according to the law … prisoner number … is condemned to death. Let this be a warning …..”

Reichsfuehrer SS Heinrich Himmler

Again, the Yiddish and the original Night agree. However, no trained member of the SS, or even the Wehrmacht, would ever have shown such disrespect as to use Himmler’s name in such a formal context without his full title: Reichsfuehrer SS Heinrich Himmler. Marion Wiesel tried to fix the error by adding “Reichsfuehrer,” but she still gets it wrong: you don’t drop the “SS.” On its own, this tells us that the speech was an imaginary one invented by the author (whoever that is), someone who was never present at such a scene. Indeed, lack of knowledge about how the SS functioned in the camps is evident throughout the book. For example, the SS did not normally go inside the barracks; everything inside was handled by the kapos.

6. Ten days and ten nights … or just “days and nights”

UdV Page 207: Tsen teg un tsen nekht hot gedoyert di reyze. / Ten days and ten nights the trip lasted.

LN Page 155: Dix jours, dix nuits de voyage. Il nous arrivait de traverser des localités allemandes.

SR Page101: Ten days, ten nights of traveling. Sometimes we would pass through German townships.

MW Page 100: There followed days and nights of traveling. Occasionally we would pass through German towns.

In January of 1945, as the advancing Red Army approached Auschwitz, a decision was made to evacuate, sending the prisoners to other camps in Germany. Evacuation of the Monowitz (Auschwitz III) camp, to which Eliezer and Father had previously been transferred, began at 6 p.m. on January 18. The prisoners were given extra clothing and food—bread to carry with them. They also had whatever food they had saved up. After marching all night during a snowfall, they rested in the morning in an old brick factory. In late afternoon, they began again and reached Gleiwitz camp in a few hours [night, Jan. 19]; they then remained in Gleiwitz barracks for three days. On the 22nd they went to the train stop and waited until evening. They were brought bread for the journey. The convoy set out

From there, as we see above, the Yiddish, the 1958 French and 1960 English versions agree on the trip lasting ten days and nights. But Marion Wiesel removes the number ten because it makes Eliezer’s timeline for the death of his father on Jan. 28/29 completely impossible. Another very significant change. Ten days and nights from the night of Jan. 22nd is the night of Feb 1, 1945.

This shows that the author of Un di velt knew nothing about the transport that arrived at Buchenwald on January 26 with 3000 prisoners from Auschwitz. This is the transport that, according to existing official records, brought Lazar and Abraham Wiesel to Buchenwald, who were registered at the camp there on . . . January 26, 1945! (See Buchenwald Archivist Cannot ID Elie Wiesel, How True to Life is Wiesel’s description of Buchenwald, and Gigantic Fraud Carried Out.)

7. Fifteen … or sixteen?

UdV Page 213: I was fifteen years old then. Do you understand—fifteen? Is it any wonder that I, along with my generation, do not believe either in God or in man; in the feelings of a son, in the love of a father. Is it any Wonder that I cannot realize that I myself experienced this thing, that my childish eyes had witnessed it? (This passage from Moshe Spiegel’s stand-alone translation of Chapter Six of Un di velt hot geshvign, published as “The Death Train” in the 1968 volume Anthology of Holocaust Literature.)

LN Page 158: J’avais quinze ans. / I was fifteen.

SR Page 103: I was fifteen years old.

MW Page 102: I was sixteen.

In the original versions, Eliezer repeats that he is fifteen years old in January 1945. Elie Wiesel’s birth date is Sept. 30, 1928 so on that day in 1944 he became sixteen years old, making him 16 years and 4 months when this particular event on the train to Buchenwald occurred in late January 1945. Once again, Marion Wiesel simply changes the age as she did before — if Elie was actually sixteen at that time, then Eliezer, the character in the book, must be too!

In Part Two, I will construct the timeline of the events in Buchenwald following the arrival of Eliezer and his father, and other details about Buchenwald. What will we find out? Stay tuned.

Endnotes:

1. On the back cover of the original hardcover Night, with the black & white striped jacket (as pictured here), it is printed “Literature” as the classification.

2. Ruth Franklin, A Thousand Darknesses: Lies and Truth in Holocaust Fiction, Oxford University Press, 2011, pp 71-72.

Unfortunately, Night is an imperfect ambassador for the infallibility of the memoir, owing to the fact that it has been treated very often as a novel—by journalists, by scholars, and even by its publishers. Lawrence Langer, in his landmark study The Holocaust and the Literary Imagination, notes that Night “continues to be classified and critically acclaimed as a novel, and not without reason.” . . .

Nonetheless, in 1997 Publishers Weekly columnist Paul Nathan had to issue a correction apologizing for referring to the book as an “autobiographical novel”; he had been misled, he said, by the entry on Wiesel in The International Dictionary of Twentieth-Century Biography. In response, the correction itself was challenged by the director of Penguin Reference Books, publishers of the biography dictionary, who cited half a dozen sources to the effect that Night was in fact a novel. Together with most critics, Gary Weissman, who recounted the above history in his book Fantasies of Witnessing: Postwar Efforts to Experience the Holocaust, seems to concur with Ernst Pawel’s remark in an early magazine survey of Holocaust fiction, that “the line between fact and fiction, tenuous at best, tends to vanish altogether in autobiographical novels such as Night.” The hybrid terms used to describe it include “novel/autobiography,” “non-fictional novel,” “semi-fictional memoir,” “fictional-autobiographical memoir,” “fictionalized autobiographical memoir,” and “memoir-novel.

GO TO PART TWO

19 Comments

Category Featured | Tags: Tags: Auschwitz-Birkenau, Buchenwald, Elie Wiesel, Holocaust fraud, Marion Wiesel, Monowitz, Night, Oprah Winfrey, Ruth Franklin, Un di velt hot geshvign,

Social Networks: Facebook, Twitter, Google Bookmarks, del.icio.us, StumbleUpon, Digg, Reddit, Posterous.