Posts Tagged ‘Night’

Sunday, July 28th, 2013

By Carolyn Yeager

Copyright 2013 Carolyn Yeager

(last edited on 7-30-13)

“How puzzling all these changes are! I’m never sure what I’m going to be, from one minute to another.”

― Lewis Carroll, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland

Introduction: In Elie Wiesel’s book Night, we find the scenario and characters changing often, and in many cases, with little rhyme or reason that is apparent to the reader. One easily concludes that, like Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, it is a work of absurdity.

In Lewis Carroll’s classic, nothing makes sense because nothing has to make sense – the intention was to be a “childish” type of foolishness or make-believe from the start. It is an example of literary nonsense (1) genre. Interestingly, we find similar examples of nonsense and absurdity in many of the stories and writings of self-proclaimed “holocaust survivors” – and we put Elie Wiesel into this category. This is why Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland is such a good fit for a parody of Elie Wiesel’s Night.

Cast of Characters:

Elie = Elie Wiesel

White Rabbit = Ken Waltzer

Father = no such person has been found

The King and Queen of Hearts = SS-Totenkopfverbände (SS-TV)

The Duchess = Hilda Wiesel

The Cheshire Cat = Carolyn Yeager

The March Hare = Antonin Kalina, Czech communist block leader

The (Mad) Hatter = Gustav Schiller, Polish Jew block leader

Elie is quite bored one warm afternoon at the Jewish orphan’s mansion in France where he lives. This is not unusual for Elie, who has absolutely nothing to do all day but play chess or study the Talmud or other holy texts of which he is known to be almost fanatically fond. Today, though, no one was around the chess table that had been set up outdoors under a large tree, and Elie becomes a bit dreamy, maybe even sleepy. He is suddenly brought wide awake again when he sees a White Rabbit run by, looking at its pocket watch and muttering “Oh dear, oh dear, I’m going to be late!”

Elie, having never heard a rabbit speak to itself before, let alone have a pocket watch, impulsively runs after the comical creature right into a large rabbit hole. He feels himself slowly falling a long distance before he comes to solid ground. When he does, an unrecognizable landscape of trees, shrubs and creatures such as he has never seen before greets his blinking eyes, and a feeling of being an innocent young girl in an enchanted garden comes over him.

Elie, having never heard a rabbit speak to itself before, let alone have a pocket watch, impulsively runs after the comical creature right into a large rabbit hole. He feels himself slowly falling a long distance before he comes to solid ground. When he does, an unrecognizable landscape of trees, shrubs and creatures such as he has never seen before greets his blinking eyes, and a feeling of being an innocent young girl in an enchanted garden comes over him.

Before he can wonder too much at this, he catches sight of the White Rabbit again and follows him until he is stopped by a barbed wire fence. Standing before it, just the thought of how he might squeeze through the wires to the other side as the rabbit did causes him to shrink to just the right size to step through. As he does—suddenly—he is in a closed railway car with many other people, Jews like himself.

Elie is so unhappy at this turn of events he begins to cry. He cries so much and so hard his tears flood the rail car, making all the others inside very angry, including his own late father whom now, however, seems to be very much alive. As the water made up of Elie’s tears rises closer to the top of the boxcar, the door opens and the inhabitants swim out with the rushing flood.

Appearing for all the world like a catch of wet fish flapping on the platform, the unfortunates find themselves being questioned by a large Caterpillar-looking officer seated on a high stool smoking a hookah. But not one of them is able to answer the officer’s questions as to the particulars of who they are.

“I’m afraid I can’t explain myself, sir. Because I am not myself, you see?”

― Lewis Carroll, Alice in Wonderland

The Camp Buchenland

The hookah-smoking officer tires of their inability to name themselves and, pointing in a certain direction, tells them to march that way to a camp where they will get dry clothes. Once there, the group lines up in an open assembly area and is told they are in Buchenland, the kingdom of the Queen of Hearts who, in spite of her kindly-sounding name, gives orders that must be obeyed. Ordered to now go to the showers where they would also receive the promised new clothing, Elie and Father already fail to obey.

The entrance to the showers is crowded with pushing, shoving people. Father sits down on the ground outside, “I can’t go on anymore; I’ll wait here until we can go into the showers.” As the two lose themselves in an argument over the subject of impending death, the electric lights go out and a loudspeaker commands that all must now be in their assigned barracks.

In haste, Elie follows a crowd into a nearby barracks, where, still unshowered, he falls to the floor and sinks into a dreamless sleep. It is only in the morning that he realizes he is alone; he must have lost his father in the rush to the barracks, and then forgotten about him! Going in search, he wanders about the camp for hours, unmolested by any officers or guards of the Kingdom. Happening upon a place where coffee is being distributed, he gets in line for a cup and magically hears the voice of his father calling to him.

From then on, for the next 7 days (as well as days can be counted in Buchenland), Elie keeps coming back to his father, looking after him in a rather haphazard fashion. Father is not well, not well at all, and Elie, “for a ration of bread,” is able to secure a cot next to his father in the barracks.(2) But a few days later, Elie is sleeping on the upper bunk, above his father, because of his (Elie’s) bandaged foot.(3)

The time comes that Father passes his last breath in his bunk during the middle of the night. According to Elie’s reckoning, it is February 8th-9th, 1945. But elsewhere, Elie states his father died on the night of January 28-29, and again on the 18-19 of Shevat, 5705, which corresponds to February 1st.(4) Elie is both secretly relieved and personally devastated over the loss of Father and blames it on the cruelty of the officials of the Kingdom of Buchenland, calling it murder.

The Queen of Hearts learns about young Elie’s defamations against her health care system, and at the same time the multiple death dates he asserts for his father, and proclaims with great indignation that this cannot be allowed in her Kingdom. The King agrees and they summon the culprit to their presence. After listening to Elie’s disconnected narrative of how he came to be in Buchenland and how he lost his father, she loses patience with the constantly changing versions of his story and shouts “Off with his head!”

Elie is put on trial

Elie is taken to court to be tried for the offense of butchering his father’s date of death. The King and Queen are seated on the high bench. Elie is formally charged with reckless endangerment of the facts of his father’s death. To everyone’s surprise, The Duchess arrives at the court, accompanied by her cat, and asks to testify for the accused. She is granted her request and takes the stand.

You know, [father and son] did a long march from Auschwitz, then they put them on the train to go to Buchen[land]; [Father] died gasping for air. When he stepped off the train, he died gasping for air; at Buchen[land]. But [Elie] knew the date.(5)

The Queen frowns; she is impatient of such testimony that adds even another version of the death in question—what can The Duchess be up to anyway? Then the Duchess’ Cheshire Cat begins to speak, saying the entire court is out of order because the father of the defendant is not the same as the 44-year old man who actually died and is listed in the Buchenland death records; therefore the date that Elie’s father died is irrelevant. Angered to hear it said that her court is out of order, the Queen shouts “Off with his head!” pointing to the Cheshire Cat. As the Queen’s guards move toward the cat to seize him, he cleverly disappears his body, leaving only his head for the spectators to see. How then can his head be chopped off?

Realizing she has been outwitted by a cat, the Queen then turns to Elie and declares him “Guilty! Off with his head!” As Elie is being escorted to the place of execution, he and his guards meet up with the Cheshire Cat again, now sitting in a tree. The Cat advises them to go to the March Hare’s house instead, warning, however, that the Hare is quite mad. “But then, everyone here is mad,” the Cheshire Cat adds with a grin, before he disappears altogether, leaving only his grin still floating in the air.

“Who in the world am I? Ah, that’s the great puzzle.”

― Lewis Carroll, Alice in Wonderland

The Hatter’s Tea Party

The White Rabbit is again spotted running ahead as if leading them to the house of the March Hare, which turns out to be another barracks, this one called the “Children’s Block.” Inside, the Hare and his companion The Hatter (also mad—in fact “mad as a hatter”) engage the children in a continual tea party intended to take their minds off the dreariness of their surroundings.

Elie, feeling grateful (for a change) to still have his head on his shoulders, takes a place at the tea table. He is hoping for something good to eat, as he has now lost interest in everything around him except food. But while the Hare and the Hatter provide nothing in the way of food themselves, Elie still finds the tea party routine—one of constantly changing seats, asking unanswerable riddles and reciting nonsensical poetry— much to his liking.

The Hatter has red hair, carries a big stick and likes to boss the children around in his Polish Yiddish. The March Hare is actually of Czech origin and is known to be at his most mad during the month of March, which it happens to be at this very time. Thus do the days pass in the children’s block.

The overthrow of the Queen

However, when the month of April rolls round, the Queen of Hearts discovers that Elie has been hidden in the house of the March Hare and commands the whole place be evacuated. Every day, for several days, Elie is marched to the camp gate with the other children—rumor has it either to be taken away and disposed of or to be given bread and marmalade outside the gate—but every day he is stopped right before the gate and returned to the March Hare’s house. No marmalade and no explanation given.

On the 11th, the enemies of the Queen from outside Buchenland arrive in such great numbers that all the King and Queen’s guards are forced to flee, leaving Buchenland in the hands of the Mad Hatters and the March Hares. In their celebratory mood, on the third day of what they term the “liberation,” they throw open the Queen’s royal pantries and a real party begins. Elie greedily gorges himself on whatever comes first to hand, causing a poisonous shock to his system. He falls unconscious, is taken to a hospital and doesn’t recover for two weeks.

Buchenland doesn’t even notice Elie’s absence. The new owners are busy taking photographs(6), writing publicity propaganda and giving tours of the place. Hunting down every last subject of the former Queen also occupies their attention. The non-descript intruder named Elie (not the only one so named!) is quickly forgotten.

But for this particular Elie, when he awoke again, it was like being reborn. The absurd world he had found himself in after following that White Rabbit down the rabbit hole existed no more; he was back at the mansion in France, unthreatened by any harm. It must have been a dream, he thought. But then, “I shall write about what I remember—now, before I forget. Even though it didn’t really happen, perhaps it could have happened. And since it’s there in my mind like a memory, that makes it real enough! Plus it’s a jolly good story.” So, going inside the mansion, he found paper and pencil and began writing of his amazing adventure in Buchenland, as he remembered it. And he called it Night.

“Why, sometimes I’ve believed as many as six impossible things before breakfast.”

― Lewis Carroll, Alice in Wonderland

Endnotes:

1. Literary nonsense (or nonsense literature) is a broad categorization of literature that uses sensical and nonsensical elements to defy language conventions or logical reasoning.

Nonsense is distinct from fantasy, though there are sometimes resemblances between them. Everything follows logic within the rules of the fantasy world; the nonsense world, on the other hand, has no system of logic, although it may imply the existence of an inscrutable one, just beyond our grasp.

2. “For a ration of bread I was able to exchange cots to be next to my father.” Night, Marion Wiesel translation, 2006, p.108.

3. “The sick stayed in their bunks [during roll call]. My father and I thus stayed inside. He — because of his dysentery and I — because of my bandaged foot. Father was lying in the lowest bunk and I — in the uppermost.” Un di Velt hot geshvign, 1955, p.235.

The bandage refers to the foot operation the fictional Eliezer had before he left Monowitz on or about Jan. 15-16. Could he still be wearing the same bloody bandage he arrived with? Of course not—which means he received treatment that he doesn’t want to tell about.

There is no mention in Night that Wiesel’s foot was still bandaged after 7 days in Buchenwald, and that he could be considered “not fit” for even the ordinary routine. After the march on foot to Gleiwitz, from Auschwitz, Elie never again refers to his foot in Night.

4. http://www.eliewieseltattoo.com/night-1-and-night-2%E2%80%94what-changes-were-made-and-why-part-two/

5. From Hilda Wiesel’s testimony to the Shoah Foundation in 1995. According to the time line in Night, she is speaking of February 1, 1945. According to the official time line, it is Jan. 26, 1945. http://www.eliewieseltattoo.com/night-1-and-night-2%E2%80%94what-changes-were-made-and-why-part-two/

6. Including the Famous Buchenwald Liberation Photo, taken on April 16, 1945 in Barracks #56 while the fictional Eliezer was in the hospital recovering from his fictional food poisoning.

15 Comments

Category Featured | Tags: Tags: Alice in Wonderland, Camp Buchenland, Cheshire Cat, Childrens Block, Elie Wiesel, Hilda Wiesel, Ken Waltzer, Lewis Carroll, literary nonsense, Night, Queen of Hearts,

Social Networks: Facebook, Twitter, Google Bookmarks, del.icio.us, StumbleUpon, Digg, Reddit, Posterous.

Tuesday, June 11th, 2013

[Continuation from “Is it time to call Ken Waltzer a fraud?“]

by Carolyn Yeager

by Carolyn Yeager

copyright 2013 carolyn yeager [last updated 12-5-2015]

“In literature, Rebbe, certain things are true though they didn’t happen, while others are not, even if they did.” –Elie Wiesel speaking of his book Night, from his Memoir: All Rivers Run to the Sea

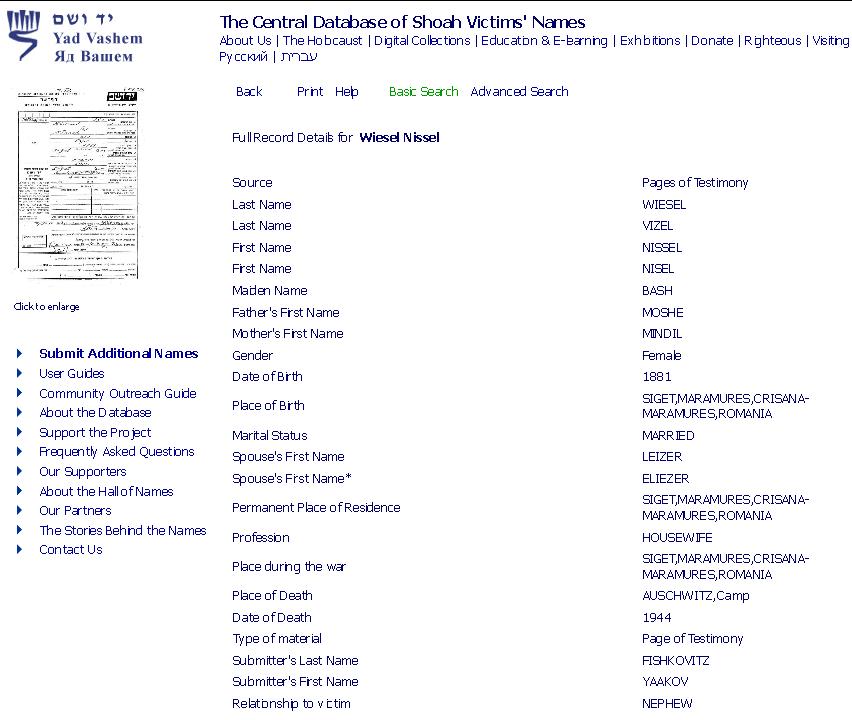

For the skeptics and know-nothings who have written in suggesting Eli Wiesel was not in the camps, that Night is purely fiction, you are all dead wrong. The Red Cross International Tracing Service Archives documents for Lazar Wiesel and his father prove beyond any doubt that Lazar and his father arrived from Buna to Buchenwald January 26, 1945, that his father soon died a few days later. –Kenneth Waltzer in a comment at Scrapbookpages Blog, March 6, 2010.

The story that Michigan State University history professor Kenneth Waltzer has told us about Elie Wiesel in Buchenwald, based on Wiesel’s book Night, is not true.1

Elie Wiesel was not incarcerated at Buchenwald.

He was not liberated from Buchenwald.

He was not a victim of the “Nazis” there.

How do we know that?

Well, how do we know that Elie Wiesel was at Buchenwald?

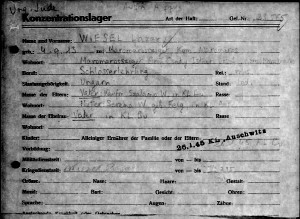

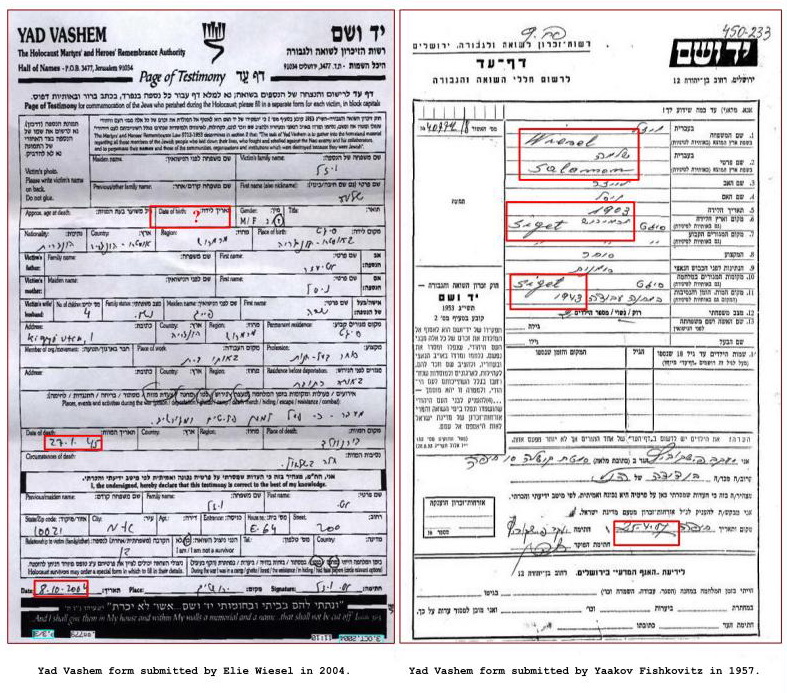

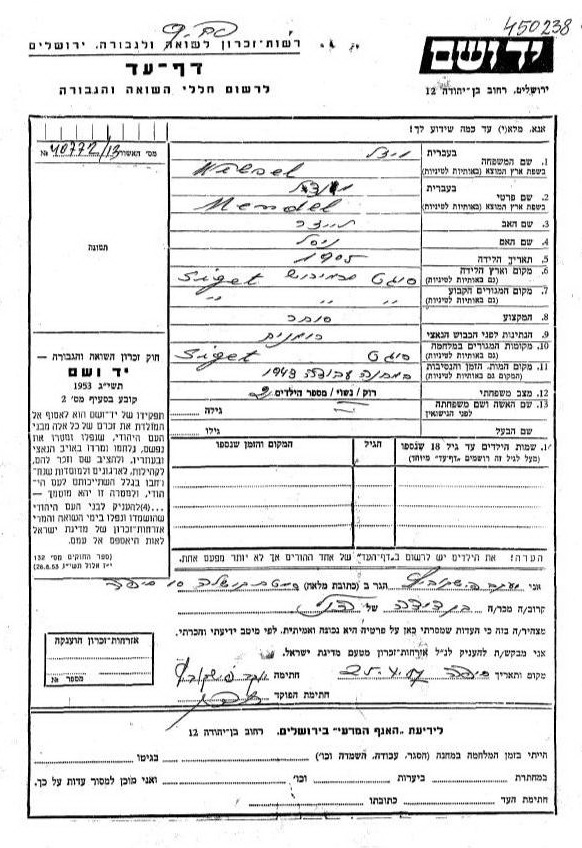

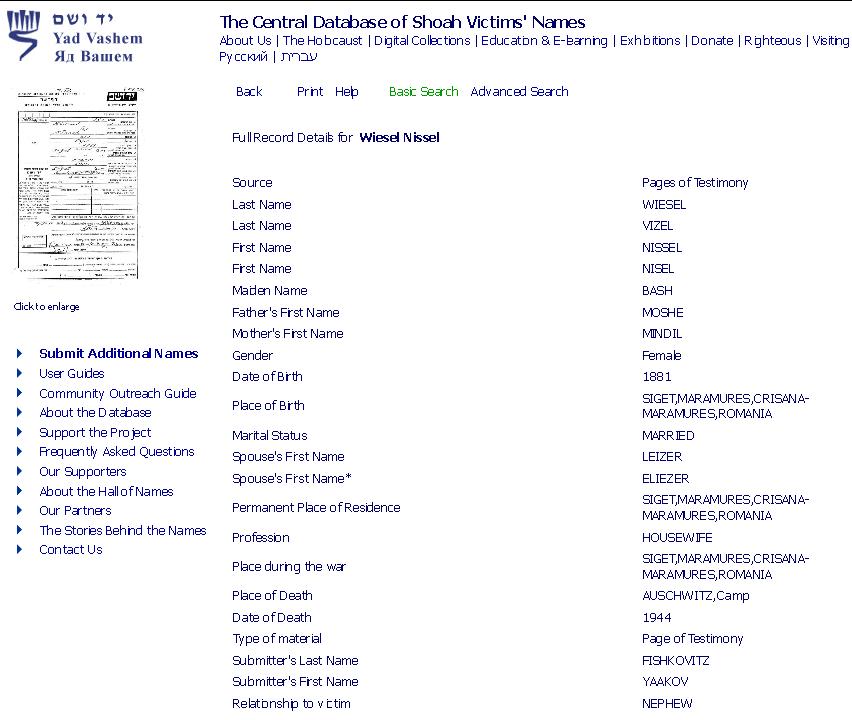

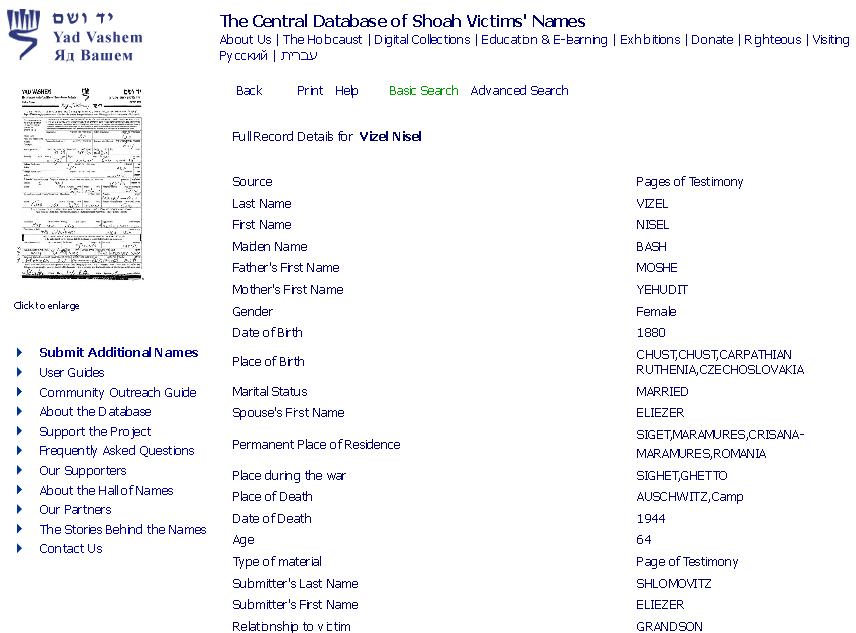

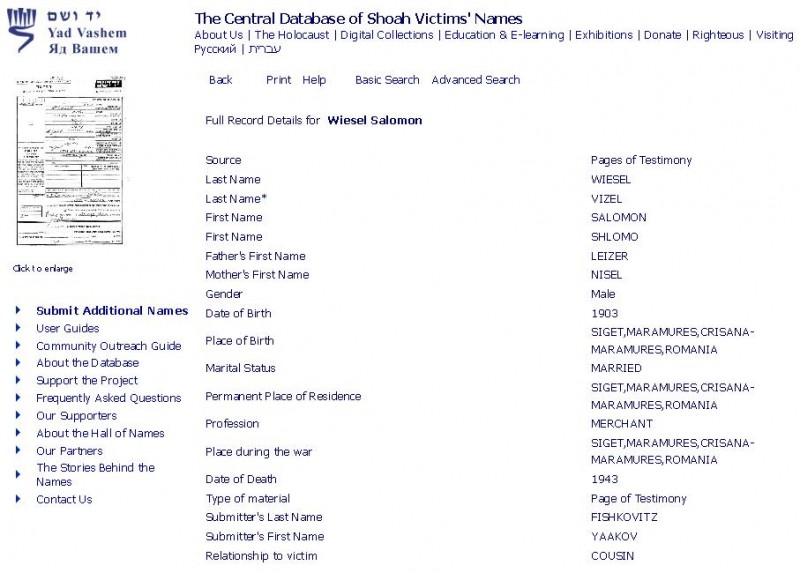

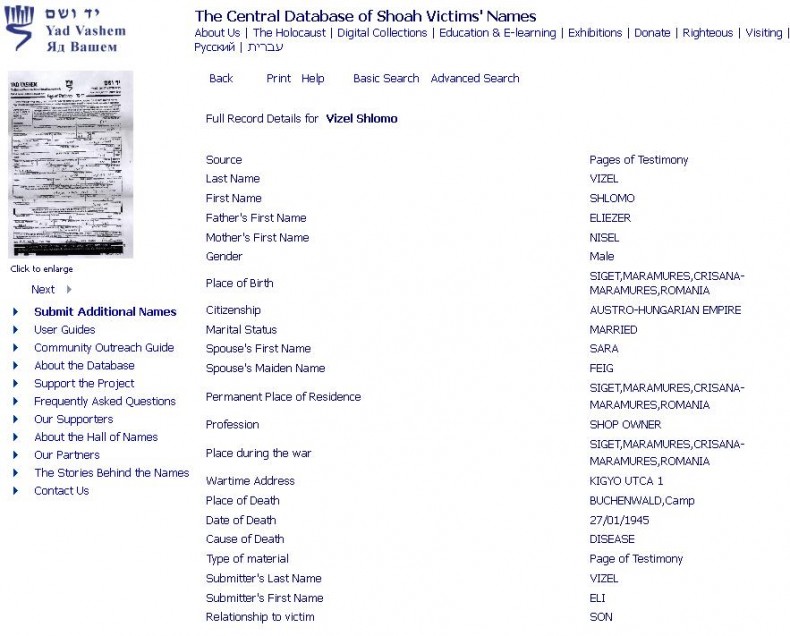

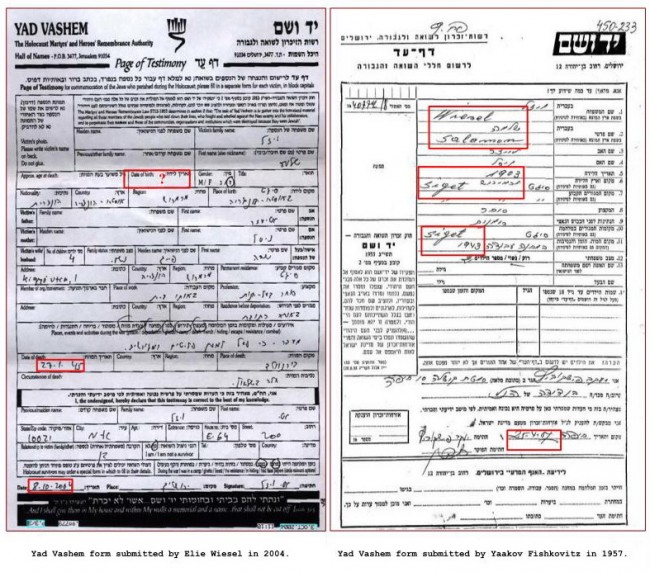

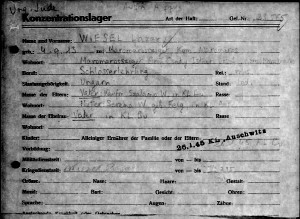

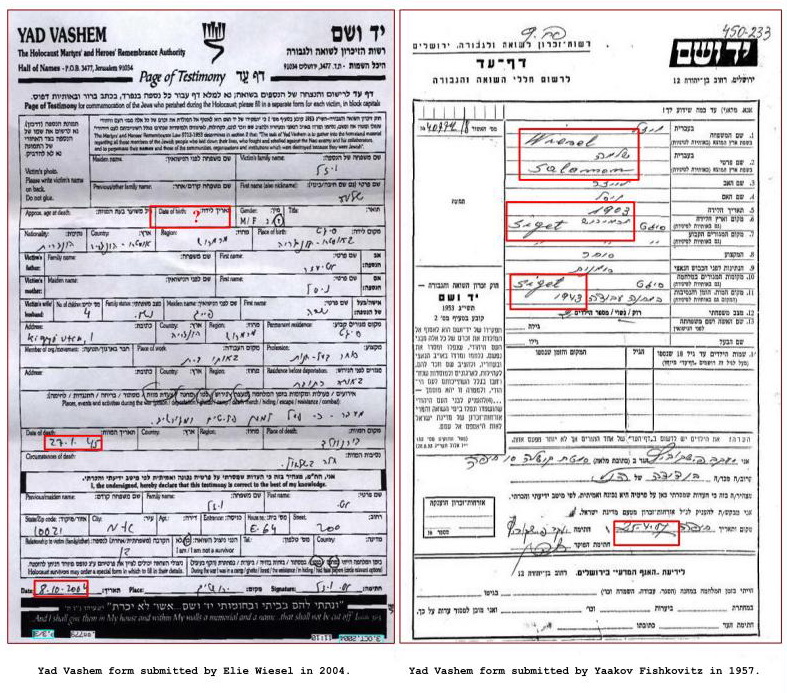

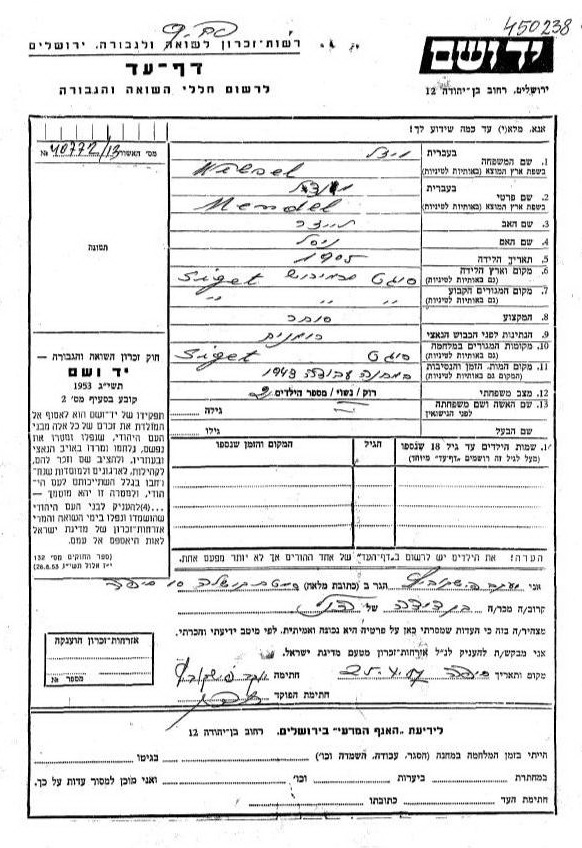

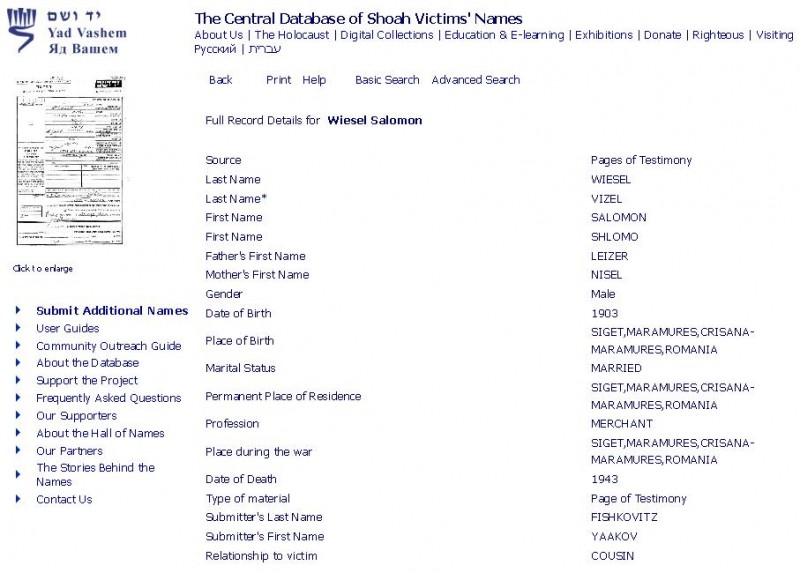

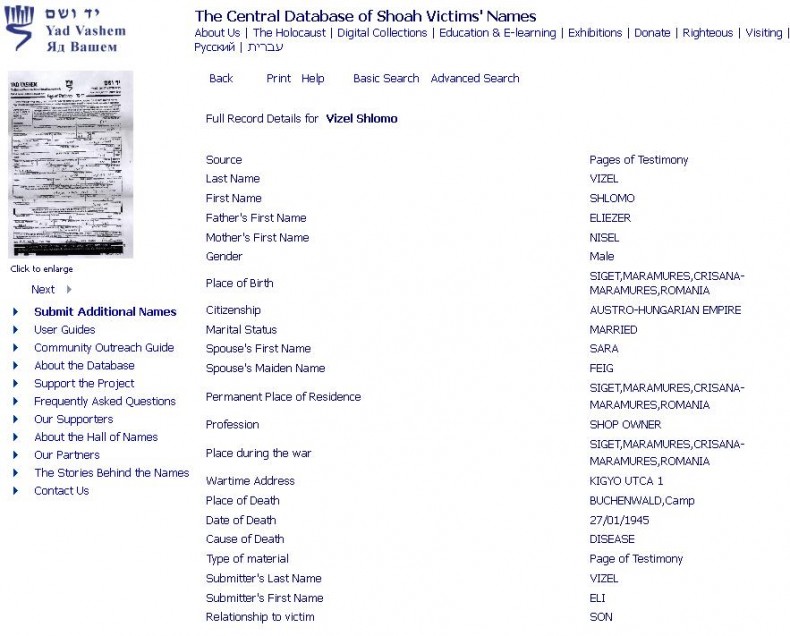

1. We have a numerical file (registration) card for Lazar Wiesel from Sighet, born 1913.

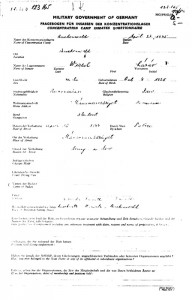

2. We have a questionaire (Fragebogen) made out for and signed by a Lázár Wiesel, a 16-year old Jew from Sighet.

3. We have a transport list from Buchenwald to France with the name Lazar Wiesel, born Oct. 4, 1928.

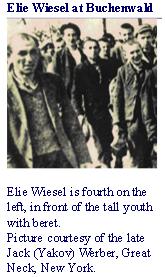

4. We see a picture of him in the famous photograph taken in Barracks #56 on April 16, 1945.

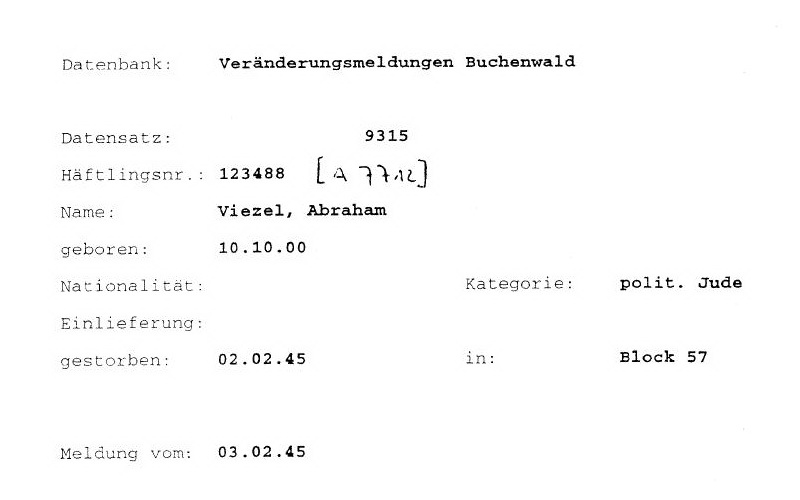

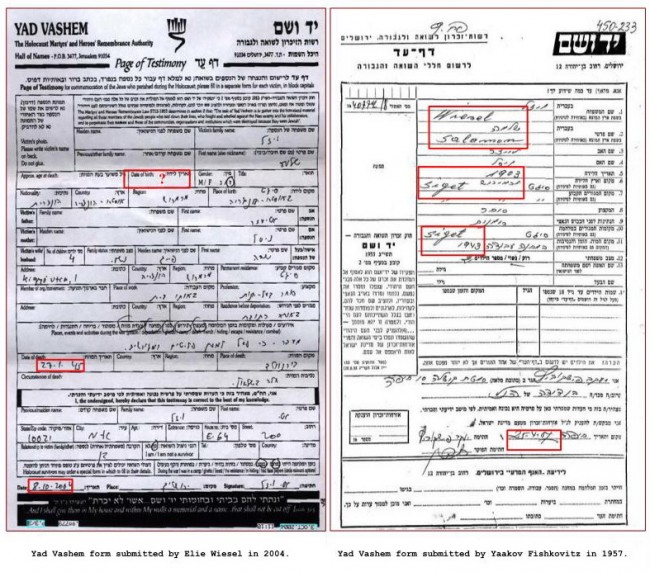

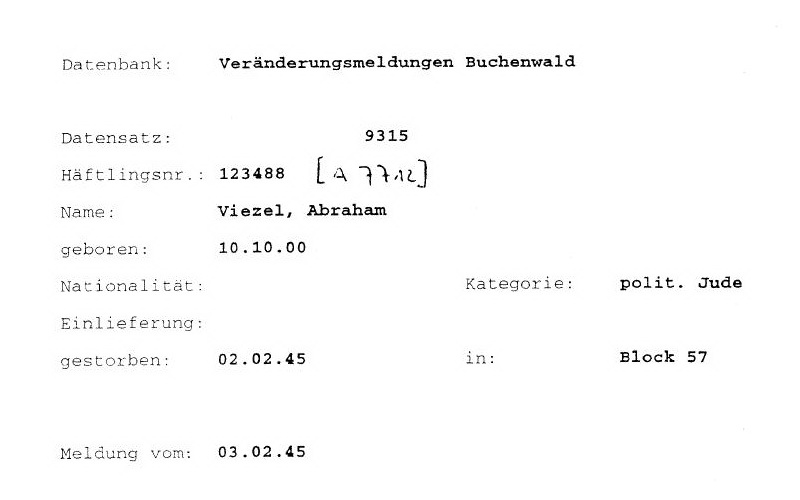

5. We have a death report for Abraham Viezel (not Schlomo or Solomon) on 2-2-1945, in Block 57.

6. We have a transport list from Auschwitz to Buchenwald with the names Lazar Wiesel, #123565, born 4 September 1913 and Abram Viezel, #123488, born 10 October 1900.

7. We have a photo of the “rescued children” marching out of the Buchenwald main gate on April 27, 1945.

8. We have the book Night, in which he says he was.

* * *

The above list is ordered according to its perceived importance in proving Wiesel was at Buchenwald, so I’ll start from the bottom (least important) in showing that they don’t prove any such thing.

8. The persuasiveness of the book Night has been dealt with in several other places, for example here and here, and is not considered evidence.

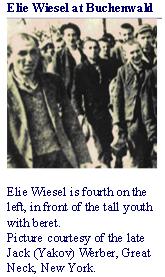

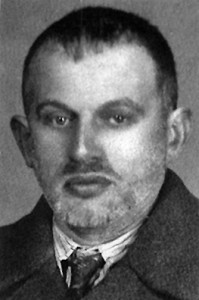

7. Photo of Buchenwald Boys (scroll down a bit). The boy that Ken Waltzer has identified as Elie Wiesel (who was identified to him as such by Jack Werber of Great Neck, NY, a “holocaust survivor” activist) is clearly not Wiesel and has not been identified as Wiesel by anyone other than Ken Waltzer. Waltzer had this image/blurb, at right, on his MSU website for years [the site was removed sometime in 2012], making him look foolish. Will Waltzer admit that he was wrong all this time, or try to sweep it under the proverbial rug?

7. Photo of Buchenwald Boys (scroll down a bit). The boy that Ken Waltzer has identified as Elie Wiesel (who was identified to him as such by Jack Werber of Great Neck, NY, a “holocaust survivor” activist) is clearly not Wiesel and has not been identified as Wiesel by anyone other than Ken Waltzer. Waltzer had this image/blurb, at right, on his MSU website for years [the site was removed sometime in 2012], making him look foolish. Will Waltzer admit that he was wrong all this time, or try to sweep it under the proverbial rug?

6. The Transport List to Buchenwald only proves that Lazar Wiesel, age 31 (a locksmith by trade) and Abram Viesel, age 44, arrived at Buchenwald on January 26, 1945 from Auschwitz. See here and here. Elie’s father’s name was Solomon (Schlomo); he never went by Abram, nor did Elie ever go by “Lazar.” Lazar had been given the Buchenwald number 123565, while Abram had 123488. There is no honest way to turn these two into Eliezer Wiesel and his father. Both the birth dates and the names are wrong. It only proves that Elie Wiesel claimed for himself the Auschwitz prisoner number (A7713) of another man. Where is the tattoo on Elie’s arm that reads A7713?

5. The Death Report for Abraham Viezel, Buchenwald prisoner number 123488, same as on the transport list. His death is recorded as taking place in Block 57 on February 2, 1945, not Jan. 29, 1945 as is clearly stated in Night for Eliezer’s father.2

4. The Famous Liberation Photo taken at Buchenwald on April 16, 1945 is said to show Elie Wiesel among the men in the bunks. Beside the fact that the face pointed out as Elie’s doesn’t look like him (for reasons which have been made clear here and here) and that he did not identify himself in it until 1983 when the campaign to get him a Nobel Prize began, there is also his hospitalization which began on April 14th.3 He could not have been near death in a hospital and in the picture at the same time! Ken Waltzer took the liberty of changing the date the photo was taken to April 12 or 13th to get around that inconvenient fact.4

3. The Transport List to France. When did Elie Wiesel’s birthday change to Oct. 4th from Sept. 30th? A majority of boys on this list share the birth year of 1928. The person listed as Lazar Wiesel is the same Lazar Wiesel that the Questionaire refers to, but we have determined that this person could not have been Elie Wiesel. It is true that Elie Wiesel went to France, but how he got there, and when, is not clear.

2. The Questionaire [scroll down page] was apparently prepared for and signed by every prisoner prior to their release. It is dated April 22, 1945; the prisoner number is 123165, different by one digit from our previous Lazar Wiesel #123565, and is the number belonging to a recently deceased inmate, Pavel Kun,5 whose death is recorded as March 8, 1945. Since Elie Wiesel allegedly received his number upon arrival on Jan. 26, 1945, he would not later be given a new number from a prisoner who just died. It would seem from this that Lázár Wiesel is a newcomer-of-sorts who had been given a number that had just been released.

2. The Questionaire [scroll down page] was apparently prepared for and signed by every prisoner prior to their release. It is dated April 22, 1945; the prisoner number is 123165, different by one digit from our previous Lazar Wiesel #123565, and is the number belonging to a recently deceased inmate, Pavel Kun,5 whose death is recorded as March 8, 1945. Since Elie Wiesel allegedly received his number upon arrival on Jan. 26, 1945, he would not later be given a new number from a prisoner who just died. It would seem from this that Lázár Wiesel is a newcomer-of-sorts who had been given a number that had just been released.

The name Lázár is spelled with distinct, heavy accent marks; the birth date given is Oct. 4, 1928 (Elie’s is Sept. 30); date of arrest is April 16, 1944 (Elie’s family’s deportation was at the end of May/early June – see here); the signature on the back does not match Elie Wiesel’s known signature or handwriting. The signature is also written with accents over the a’s in Lázár, implying that the accenting originated with Lázár and not with the official who filled out the form.6

But, beyond all this, on April 22 Elie Wiesel, by his own account, was in a hospital in or near Buchenwald camp “hanging between life and death” after coming down with severe food poisoning. He was taken to the hospital on April 14 and not released until April 28, according to his own words in his “autobiographical” Night and his 1995 memoir All Rivers Run to the Sea. Therefore, he could not have been interviewed or signed the questionaire on April 22nd. (See Endnote 3)

1. The Numerical File Card (below), made out at registration, is for Lazar Wiesel from Maromarossziget, born Sept. 4, 1913, making him at the time 31 years old. His Buchenwald prisoner number 123565 is written on the upper right. The card indicates his father, Szalamo Wiesel, was also at Buchenwald, while his mother, Serena Wiesel, nee Feig was currently interned at KL Auschwitz (at the time of Jan. 26, 1945).

This registration card is the only item that casts some doubt7 over Nikolaus Grüner’s account of Lazar and Abram. But it does not prove that this Lazar Wiesel is Elie Wiesel. It does not make any sense that all the birth dates for the same person would be different! It makes more sense that there were several persons with similar names.

This registration card is the only item that casts some doubt7 over Nikolaus Grüner’s account of Lazar and Abram. But it does not prove that this Lazar Wiesel is Elie Wiesel. It does not make any sense that all the birth dates for the same person would be different! It makes more sense that there were several persons with similar names.

Note that this card identifies Lazar Wiesel as a locksmith (Schlosserfehrling), a trade of which the 15-year-old Elie Wiesel never would have identified himself. In Night he identified himself upon entry to Auschwitz as “a farmer” (p. 32, MW translation) and continued not to boast of any skill (of which he had none anyway) so as not to be sent out for work.

* * *

So we end up realizing there is no evidence that Elie Wiesel ever set foot in Buchenwald in 1945. What’s more, he and others (including Ken Waltzer) have actively and knowingly lied about photographs, dates, times, names, etc. This has gone on with the blessing and support of Yad Vashem Holocaust Memorial in Israel, the US Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington DC, the New York Times Company, Associated Press, and other establishment media – and the multitude of Jewish/Holocaust-promoting organizations across the globe. Think of Elie Wiesel conducting US President Obama and German Chancellor Merkel around the Buchenwald Memorial in 2009! It is a giant criminal conspiracy when one really takes a look at it. The ramifications are immense.

Someone, preferably Elie Wiesel, needs to explain all the discrepancies in his tale. He has never offered to and never been asked to. If Wiesel won’t attempt an explanation, then Ken Waltzer the Historian with the PhD from Harvard University must do so. In his scholarly studies, Waltzer includes Elie Wiesel as one of the “Rescued Children of Buchenwald. ” One duty of a scholar is to answer serious and justified questions about their work. Elie Wiesel Cons The World is asking such questions and so we await an answer.

Update 6-15 Great idea from a reader: Write to Prof. Ken Waltzer at [email protected] and ask him politely to answer the questions raised in this article.

Endnotes:

1. Prof. Kenneth Waltzer has removed this article from the Internet, along with his entire website which the article had been a part of for several years, and says he has written a new separate article on Elie Wiesel in Buchenwald.

The book is on track, and I have also completed a separate essay to be published on Elie Wiesel and Buchenwald. -Ken Waltzer to me, Carolyn Yeager, in an email, March 2013

He obviously doesn’t want comparisons made between his old and new article and is waiting as long as possible to make it public. Or is he still reworking it?

2. “Then I had to go to sleep. I climbed into my bunk, above my father, who was still alive. The date was January 28, 1945. I woke up at dawn on January 29. On my father’s cot there lay another sick person. They must have taken him away before daybreak and taken him to the crematorium.” –Night, 2006 Marion Wiesel translation, p. 112

The Yiddish original, Un di Velt Hot Gesvign, says Father’s death occurs on the 18-19 of Shevat:

For a couple of hours I stayed by him and looked at his face long and well […] Then they forced me to go lie down to sleep. I climbed up to the uppermost bunk and I did not know that in the morning, on awakening, I would find my father no more.

It was the eighteenth of Shevat, 5705.

Nineteenth of Shevat. Early in the morning.

I got up and ran to my father. Another sick man was lying in his place.

I had a father no more. (p 238)

Readers might be surprised to learn that the Hebrew calendar date of 18-19 Shevat, 5705 corresponds to February 1-2, 1945. This gives credence to the idea that Abram Viezel’s death is the model for the story And The World Remained Silent. The date in the original story for Father’s death and the date of Buchenwald records for Abram’s death concur. This leads me to question Elie Wiesel’s personal knowledge of events at Buchenwald because why would he change the date to Jan. 28-29 if he knew the significance of Feb. 1-2?

Also, the death took place in Block 57, the report said, which would seem to be next door to Block 56 where the famous Buchenwald liberation photo is said to have been taken.

3. “Three days after the liberation of Buchenwald, I became very ill: some form of food poisoning. I was transferred to a hospital and spent two weeks between life and death.” –Night, 2006 Marion Wiesel translation, p. 118

Also in Un di Velt Hot Gesvign (the original Yiddish story from which Night was taken), p.244:

“Three days after liberation I became very ill; food-poisoning. They took me to the hospital and the doctors said that I was gone. For two weeks I lay in the hospital between life and death. My situation grew worse from day to day.”

Another question that occurs is: Of all the photos taken in Buchenwald after liberation, why don’t we find even a single one with Elie Wiesel in it? Knowing he wasn’t there at all may be why he liked the food poisoning/hospitalization story – it can explain why he doesn’t show up in any photograps. But it totally contradicts his “evidence” of the Questionaire and of his being in the famous barracks #56 photo.

4. Waltzer wrote in his article:

“He [Elie] was too weak at liberation on April 11 to leave his barracks (hence he was photographed in a famous picture in the barracks on April 12 or 13), and he came to understand he was free only days later.”

Waltzer trapped himself again. The officially declared date of the photo is April 16, which is well established. Waltzer is simply trying to evade with lies the serious problem of Wiesel going into the hospital 2 days before the photo was taken. This is NOT how a respectable, responsible historian does things.

In addition, Waltzer is saying that the photograph was taken in the children’s barracks #66, which is utterly wrong. The official description says it was barracks #56, for men, or possibly a sick barracks. If Abram Viezel was in a sick barracks when he died (#57), then #56 might also be an “infirmary” barracks.

5. Pavel Kun is on the transport list of Jan. 26, 1945 from Auschwitz to Buchenwald. He appears under the section Politische Slowakan Juden; his birth date is July 6, 1926, making him 18 when he died.

6. Revisionist Carlo Mattogno concluded, after studying these documents, that Lazar Wiesel, Lázár Wiesel and Elie Wiesel are not the same person.

In conclusion, we can say that Elie Wiesel can be neither Lazar Wiesel, nor Lázár Wiesel, nor Lazar Vizel and that the ID number A-7713 was not assigned to him but to Lazar Wiesel, while ID A-7712 was not assigned to his father but to Abram (or Abraham) Viesel (or Wiesel).

The charge of identity theft raised against Elie Wiesel by Miklos Grüner does not concern Lazar Wiesel only, but Lázár Wiesel as well: from the former, he took the Auschwitz ID number (A-7713), from the latter the stay at Buchenwald and the later transfer to Paris. –http://revblog.codoh.com/2010/03/elie-wiesel-new-documents/#more-837

7. Szalamo seems likely a Hungarian spelling for Shlomo. Serena Feig is close but not Elie’s mother’s name, which was Sarah Feig. According to this card, Lazar had a father in the camp, something that was not mentioned by Nikolaus Grüner. Ken Waltzer will say this proves that Lazar Wiesel is Elie Wiesel, but what about the very wrong birthdate? Why don’t we have a card for Szalamo too? These cards are kept at Bad Arolson, not at the Buchenwald Memorial Museum Archive; only people with special permission (like Waltzer) have access to them.

17 Comments

Category Featured | Tags: Tags: Abramham Viezel, Buchenwald Boys, Buchenwald liberation, Elie Wiesel. Buchenwald Concentration Camp, Kenneth Waltzer, Lazar Wiesel, Night, Rescued Children of Buchenwald,

Social Networks: Facebook, Twitter, Google Bookmarks, del.icio.us, StumbleUpon, Digg, Reddit, Posterous.

Monday, April 1st, 2013

By Carolyn Yeager

copyright 2013 Carolyn Yeager

Updated April 7th

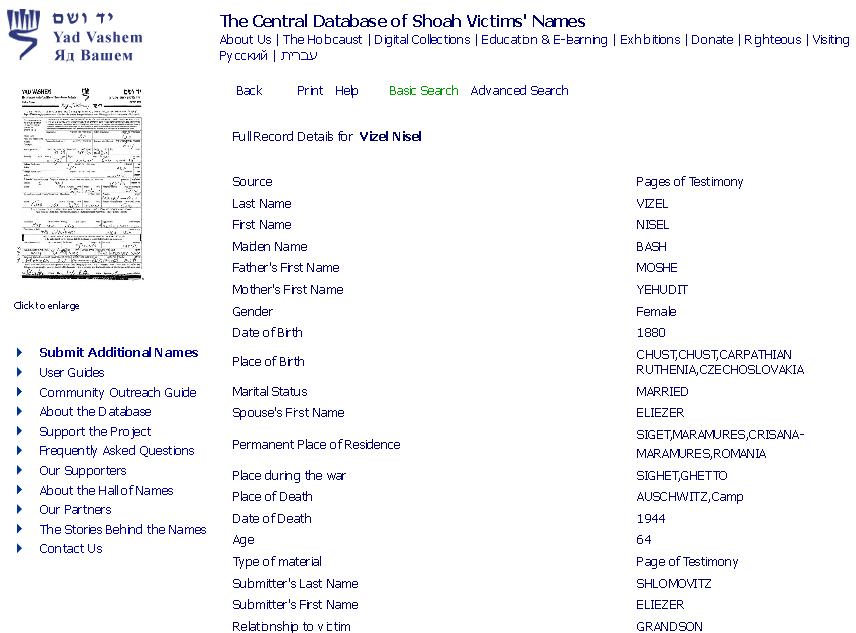

Prof. Kenneth Waltzer is looking at a Buchenwald registration card at the International Tracing Service in Bad Arolsen, Germany.

Kenneth Waltzer is a professor of history at Michigan State University since the early 1970’s. He helped to create the Jewish Studies program which opened in 1992, and which he heads. Waltzer has been researching into evidence of a special ‘boy’s protection program’ run by prisoners at Buchenwald for going on 10 years now. As an “approved” researcher, he is allowed to peruse all the files at the International Tracing Service in Bad Arolsen, Germany, something that is made much more difficult, if not impossible, for revisionists.

Waltzer is considered one of the top scholars in the U.S. of the ill-named holocaust but his work has been sloppy, and his attempts to cover up the sloppiness amount to fraud. This, along with his continual promotion and defense of Elie Wiesel as a Buchenwald survivor, is what has drawn me to study him ever more closely.

Because of the seriousness of the charge I am making against him, I will list right up front my reasons for thinking it is time for such a call. They are:

- Waltzer habitually tells fibs in the form of false information which is intended to mislead. When called out for it, he tells more fibs to cover for the first ones.

- He has been in the service of the “Holocaust Industry,” not academic rigor and fair-mindedness, from the very start of his career.

- He knowingly defrauds his students, his university and the public (you and I) with his dishonest “holocaust scholarship.”

- While he is drawing high pay as a tenured American professor of history at MSU, he is working to advance the State of Israel.

I am going to show that these charges have a strong basis in fact. Fraud is commonly understood as dishonesty calculated for advantage. A person who is dishonest may be called a fraud. In the U.S. legal system, fraud is a specific offense with certain features. (see here)

Legally, fraud must be proved by showing that the defendant’s actions involved five separate elements: (1) a false statement of a material fact, (2) knowledge on the part of the defendant that the statement is untrue, (3) intent on the part of the defendant to deceive the alleged victim, (4) justifiable reliance by the alleged victim on the statement, and (5) injury to the alleged victim as a result.

I am not intending to bring legal charges of fraud against Prof. Waltzer, but to try him in the court of public opinion. Therefore, it will be up to Waltzer to defend himself against my charges.

* * *

Two years ago, I asked the question on this web site: “What happened to Ken Waltzer’s book about the boys of Buchenwald?” It was claimed to be, at that time, in it’s final stages. Eight years after he publicly announced he was researching for a book about the so-called children’s barracks at Buchenwald (Barracks #66 ), it still has not materialized. Five years after his book was described as “upcoming,” it still has not materialized. During this time, he has not produced another book, or any major work that would have taken precedence over this book. So what is the delay?

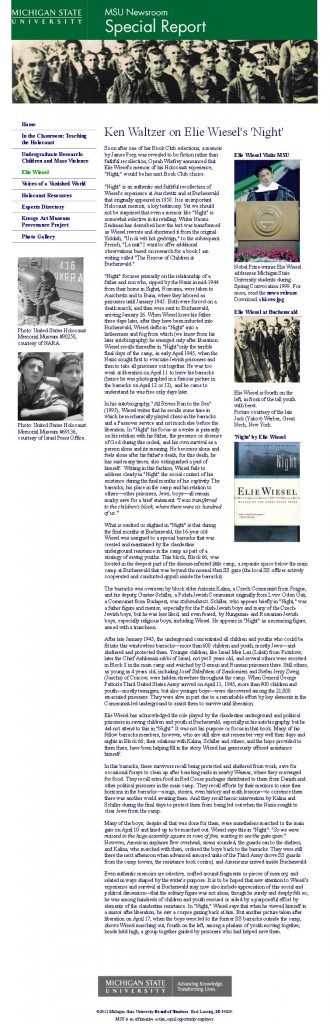

It’s pretty plain that the book’s thesis has shifted considerably since 2005, when his MSU website featured Elie Wiesel as the most recognizable and famous child survivor from Buchenwald. That website was taken down between one and two years ago and is completely wiped clean from the Internet. The banner on all the six to eight pages that were included showed a photograph very similar to the one below of the “boys” being marched out of the main Buchenwald camp to temporary quarters at the former SS barracks.

The USHMM (national holocaust museum in D.C) website dates this picture as being taken on April 17, 1945, six days after liberation.1 At this time, Elie Wiesel, by his own account in two books, was laying in a hospital sick almost unto death from food poisoning. Details like this don’t deter Prof. Waltzer from backing up in every instance the standard holocaust narrative. “Elie Wiesel in Buchenwald” is the standard narrative, so evidence must be found for it.

Ken Waltzer claimed for years that one of these boys was Elie Wiesel. But Wiesel is not in this picture!

Ken Waltzer claimed for years that one of these boys was Elie Wiesel. But Wiesel is not in this picture!

From at least 2005 (eight years now), Waltzer has identified the boy third from the front in the left-side column (dressed in a black suit, bareheaded, and in front of the tall boy wearing a beret) as Elie Wiesel, based on nothing but his own fraudulent intention that there was enough resemblance that people would believe it if he said so. In this article , I exposed this lie. Waltzer has never admitted that he was mistaken or was perpetrating a falsehood that he intended to put into his book. Instead, what he did when his fabrication was sufficiently exposed was to take the entire site down and not mention it again.

From at least 2005 (eight years now), Waltzer has identified the boy third from the front in the left-side column (dressed in a black suit, bareheaded, and in front of the tall boy wearing a beret) as Elie Wiesel, based on nothing but his own fraudulent intention that there was enough resemblance that people would believe it if he said so. In this article , I exposed this lie. Waltzer has never admitted that he was mistaken or was perpetrating a falsehood that he intended to put into his book. Instead, what he did when his fabrication was sufficiently exposed was to take the entire site down and not mention it again.

Left is a close-up of the boy Waltzer has maintained for several years is Elie Wiesel. Anyone can tell it is not and that’s why no one else ever publicly agreed with him.

I have some of what was on that site copied into articles here at EWCTW and also in my files. At left is the cropped section of the photo that Waltzer used on the banner of his MSU-Newsroom/Holocaust website that was very much dedicated to Elie Wiesel. (Another reader, Chris, informed me that he had found pages from the site using the Way Back Machine. Many thanks to him.) This shows that Waltzer definitely identified the boy in the black suit as Elie Wiesel. In addition, Jack Werber, a known dishonest survivor, was the supposed supplier of the picture.

I have some of what was on that site copied into articles here at EWCTW and also in my files. At left is the cropped section of the photo that Waltzer used on the banner of his MSU-Newsroom/Holocaust website that was very much dedicated to Elie Wiesel. (Another reader, Chris, informed me that he had found pages from the site using the Way Back Machine. Many thanks to him.) This shows that Waltzer definitely identified the boy in the black suit as Elie Wiesel. In addition, Jack Werber, a known dishonest survivor, was the supposed supplier of the picture.

Below right, a screen shot of one of the pages as it existed then, sent by a friend of EWCTW. It shows more of the emphasis on Elie Wiesel.

When I pointed out much of this in a podcast of March 25th, Waltzer sent me an email on March 28th stating,

My websites at UM FLint are down because I was appointed there one year and am now back at Michigan State.

Of course I never mentioned UM Flint and never even saw his website there. I was speaking about his MSU website, which was titled something like Ken Waltzer’s “MSU Newsroom Special Report.” It was full of information about his projects and especially what he calls “the rescue operation of children at Buchenwald.” It was up on the Net since at least 2008 2, then suddenly disappeared, with not even cache pages to be found. Did Waltzer tell me a fib, or did he just read the podcast program description and misinterpret what it said about “taking down web pages?” By now, he will know what I mean and may answer.

I think it is very possible that he timed the take-down of his MSU “Newsroom” site with his one-year visiting professorship at UM Flint — putting up a temporary website there which he could take down when he left. This is a way of confusing the picture in order to distract as much as possible from his more recent decision to put more distance between himself and his prior (false) assertions about Elie Wiesel.

I think it is very possible that he timed the take-down of his MSU “Newsroom” site with his one-year visiting professorship at UM Flint — putting up a temporary website there which he could take down when he left. This is a way of confusing the picture in order to distract as much as possible from his more recent decision to put more distance between himself and his prior (false) assertions about Elie Wiesel.

His intention was and is clearly to deceive. The harm is caused to ordinary people who believe and trust that they are getting knowledgeable answers from a professor of history and a holocaust scholar. In this particular case, all five of the elements necessary to prove fraud are there.

First, he sets up a University-sponsored website maintaining falsely that Elie Wiesel is the boy in the photograph of youthful “survivors” marching out of the camp (1). He knows it is false because he has no evidence or proof, only his own “wishful thinking.” The USHMM never identified Wiesel in that group of boys, nor did anyone else (including Wiesel himself), unless they did so from following Waltzer’s example (2). Waltzer’s intent was to make the public believe something that was not true – that he had proof of Elie Wiesel being one of the “rescued children” (3). Because Waltzer is a Professor of History and “holocaust expert” at a major university, and is at all times written up very favorably in the media, the public (you and I ) and his students will rely on his statements (4). These same students and public are injured when photographs are mislabled in order to foist on them a certain belief about an influential historical event that affects their entire world view (5).

* * *

This is just one instance of the untruths that Ken Waltzer has told over the years. Another tactic he uses is to promise an upcoming answer to your doubts which he cannot or does not produce now. As we have seen, we continue to wait as he continues to promise. Still another tactic is to accuse others of lying when it is he who is doing so. But only people who are knowledgeable enough about these complex and purposely obscured issues can see who is doing the lying. In this same email, Waltzer wrote:

The book is on track, and I have also completed a separate essay to be published on Elie Wiesel and Buchenwald.

Completed, he says. And separate. Why separate? I wrote back to him asking where I could find his essay because I wanted to read it. No reply – which is typical because factual information is not his forte, emotional rhetoric is. I feel it’s quite possible, even probable, he wrote a separate essay on Elie Wiesel so as not to tarnish his book with the false “facts” about Wiesel in Buchenwald. He can always get rid of an essay, if necessary, later – but not his entire book. What might there be in this essay? [As it turned out, the book never manifested at all –cy, 4-14-25] Will it be the same or quite different from what he wrote in a March 6, 2010 comment at Scrapbookpages Blog, when he said [my underlining-cy]:

For the skeptics [I was using the screen name “skeptic” then, at Scrapbook blog -cy] and know-nothings who have written in suggesting Eli Wiesel was not in the camps, that Night is purely fiction, you are all dead wrong. The Red Cross International Tracing Service Archives documents for Lazar Wiesel and his father prove beyond any doubt that Lazar and his father arrived from Buna to Buchenwald January 26, 1945, that his father soon died a few days later, and that Lazar Wiesel was then moved to block 66, the children’s block in the little camp in Buchenwald. THese documents are backed up by military interviews with others from Sighet who were also in block 66, and by the list of Buchenwald boys sent thereafter to France. All of this is public domain.

Wishful thinking by Holocaust deniers will not make their fantasies true. While Wiesel took liberties in writing Night as a literary masterpiece, Night is rooted in the foundation of Wiesel’s experience in the camps. The Buchenwald experience, particularly, runs closely to what is related in Night.

Comment by kenwaltzer — November 14, 2010 @ 6:57 am

How much untruth is contained in this, in order to defraud us all in his devoted service to the “Holocaust Industry” and the state of Israel? Plenty. As proof that Elie Wiesel was in Buchenwald, he points to documents for Lazar Wiesel and “his father.” It is even more absurd because Lazar Wiesel’s relative was only 13 years older than Lazar – it was in fact his brother Abram! Waltzer is passing off Lazar for Elie simply on the basis that Lazar also came from Sighet, Elie’s hometown and carries the same name. Sighet was a city of 50,000 or so with a very large Jewish population, and Wiesel was a common name. But the “scholar” who has taken years to research this and still isn’t finished, wants us to believe there can be only one Lazar Wiesel, who is Elie. He attributes the difference in their birthdates to bureaucratic error.

Previously I may have called this stupidity, but now I’m calling it fraud, based on the above-given definition. Of course Waltzer can see the discrepancies here, but he hopes he can convince you not to see them. The Military Interview mentioned with Lázár Wiesel’s name on it also does not have the right birthdate for Elie Wiesel, nor does the signature match Elie’s well-known signature.

Will Waltzer repeat this nonsense in his latest “completed” essay? Notice that Waltzer never fails in the name-calling department, here calling his critics names such as “know-nothings” and “Holocaust deniers.” Several months later, he wrote a similar comment at EWCTW to the blockbuster article: “Signatures Prove Lázár Wiesel is not Elie Wiesel”

by kenwaltzer

On November 14, 2010 at 10:34 am

Contrary to Carolyn Yeager’s wishful thinking, Eli Wiesel was indeed the Lazar Wiesel who was admitted to Buchenwald on January 26, 1945, who was subsequently shifted to block 66, and who was interviewed by military authorities before being permitted to leave Buchenwald to go with other Buchenwald orphans to France. Furthermore, there is not a shadow of a doubt about this, although the Buchenwald records do erroneously contain — on some pieces — the birth date of 1913 rather than 1928. A forthcoming paper resolves the “riddle of Lazar” and indicates that Miklos Gruner’s Stolen Identity is a set of false charges and attack on Wiesel without any foundation.

The promise of a forthcoming paper turned out to be a fib. From Nov. 2010 to now, there has not been any paper. Maybe it’s the essay he mentioned in his March 28th email? “Forthcoming” to Waltzer means up to two and a half years, it seems. That in itself is the sign of an unreliable person.

There can be only one reason Ken Waltzer allows himself to look like a buffoon and a shyster. He doesn’t need to do it to keep his position at Michigan State University. He does it because it is his larger job to keep the Buchenwald atrocity stories and Liberation lies, including the Elie Wiesel myth, alive and well in the mind of the public. He works for purely Jewish interests – I will be writing a future article on the priority, meaning and funding of Jewish Studies programs in American universities. For now, I can add that Waltzer is more of a public relations (PR) worker for the Holocaust Industry, the State of Israel and maybe AIPAC, than he is an honest-to-god academic. Another organization connected to Israel that he serves is Scholars for Peace in the Middle East. He has written four attack-dog articles for them since 2009, functioning in a sort of Abe Foxman-pitbull style.

In Nov. 2009, he attacked Alison Wier as another “know-nothing” because she speaks up for Palestinian rights on college campuses, where she is popular.

In May 2010, he went after John Mearsheimer for calling Israel “an apartheid state” and also took out after Noam Chomsky, Norman Finkelstein, and “the crackpot Phil Weiss.”

Also in May 2010, another target was Judith Butler, who campaigned at the Berkeley campus for the university “to divest from companies making military weapons which Israel employs to commit war crimes.”

In August 2011, he wrote on the Israeli-Palestinian peace process, arguing for Israel’s interests to be well and strongly presented on college campuses.

But this is only the tip of the iceberg when it comes to Walzer’s pro-Israel activities. I will be writing further articles that present the evidence for Ken Waltzer being guilty of fraud in his public writings and during his entire career. Much of it revolves around Elie Wiesel and the Industry’s need to place him at Buchenwald. My position, if you have somehow missed it, is that Elie Wiesel was never at Buchenwald. I am also saying that Waltzer is backing down or “stepping back” from his blatant, dishonest claims about Wiesel, but he can’t back down altogether.

Endnotes:

1. I have also seen it dated April 27 at the USHMM and have used that date in other articles here. Now I have only found this one picture which is very officially dated the 17th. There may have been an attempt to move the date to the 27th so that Wiesel could be in the picture (though he supposedly would not have been released from the hospital until the 28th). It is really too bad the USHMM cannot be relied upon; nor can Yad Vashem. When the museum “researchers” are involved in lying or in complacency, one really has nowhere to turn.

2. http://msutoday.msu.edu/news/2008/mapping-the-holocaust-archive-msu-prof-explores-records-of-nazi-atrocities At bottom of article, it reads “For more information, and to follow Waltzer’s research and read his journal as he participates in the workshop, visit the special report at: http://special.newsroom.msu.edu/holocaust.” This is a link to the website that no longer exists, as you will see if you click it. Now he seems to be pretending it was never there.

11 Comments

Category Featured | Tags: Tags: Abram Vizel, Buchenwald camp, Buchenwald liberation, Elie Wiesel, Holocaust Industry, Israel, Ken Waltzer, Lazar Wiesel, legal definition of fraud, M. Grüner, Michigan State University, Night, Scholars for Peace in the MIddle East, USHMM,

Social Networks: Facebook, Twitter, Google Bookmarks, del.icio.us, StumbleUpon, Digg, Reddit, Posterous.

Sunday, August 5th, 2012

By furtherglory

(First published at Scrapbookpages Blog on August 2, 2012)

Yesterday the online Chicago Tribune had an article which reported that “In recognition of [Elie] Wiesel’s vast contributions to the art of the printed word, which includes more than 50 works of fiction and nonfiction, he has been named winner of the 2012 Chicago Tribune Literary Prize.”

Yesterday the online Chicago Tribune had an article which reported that “In recognition of [Elie] Wiesel’s vast contributions to the art of the printed word, which includes more than 50 works of fiction and nonfiction, he has been named winner of the 2012 Chicago Tribune Literary Prize.”

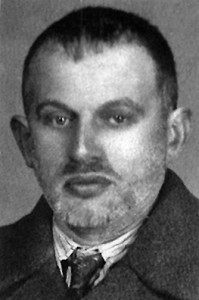

[Photo of Wiesel at left is from December 2009 in Budapest, Hungary. ]

After reading this article, I immediately checked out Carolyn Yeager’s website Elie Wiesel Cons the World to see what she has to say about this new honor for Elie Wiesel. I found a video which explains the whole story of Elie Wiesel in great detail. The video starts out with the sound of an old fashioned typewriter as the keys hit the paper, typing out the URL of the website. I love it!

The sound of the typewriter keys brought back a flood of memories; I was alive during World War II and I saw the news reels of the liberation of Bergen-Belsen and read about the liberation of Dachau. Yet I didn’t get interested in the Holocaust until many years later. My lack of interest in the Holocaust was nothing unusual, as the video on Yeager’s website points out.

The article in the Chicago Tribune also points out that there was very little interest in the Holocaust as late as 1960 when Elie Wiesel’s book Night was first published in English.

This quote is from the Chicago Tribune:

After the war, [Elie Wiesel] worked as a journalist in France for Yiddish and French publications. The noted French writer and Nobel laureate Francois Mauriac urged Wiesel to write his Holocaust memoir, and Mauriac “went from one publisher to another,” said Wiesel, to persuade them to take on Wiesel’s book.

At first, “Night” generated little interest, and the English-language publication in 1960 “sold 5,000 copies in three years,” Wiesel said. “And the same thing, by the way, in France — everywhere.”

Why was the world slow to recognize the book’s value?

“Maybe it needed — the world itself needed maybe a whole generation for readers to realize that they must know something more” about the Holocaust, Wiesel said.

As a person who was alive and well between 1945 and 1960, I can tell you why no one was interested in the Holocaust during that period. The years after World War II were the best of times. During the 1950s, everyone was extremely happy to be living during peace time; no one wanted to re-live the war. I was writing and selling magazine articles during the 1950s, but not stories about the Nazi concentration camps, which would not have been of interest to very many people at that time. There were thousands of Holocaust survivors in American during those years, but they were keeping their mouths shut and hiding their tattoos.

I lived in Germany for two years after World War II, but I didn’t bother to go to see the former Dachau camp. When I went back to Germany for the first time in 1995, I didn’t go to see the Dachau Memorial Site. The Holocaust did not become as popular as it is now until many years later. If only I had anticipated the Holocaust mania, I could have written a novel about Auschwitz and Buchenwald and become a millionaire. Many people have urged me to write a fake Holocaust memoir, but I think it is too late for me; there are too many fake memoirs on the market.

I was one of the first to put the information on the Internet that Elie Wiesel could not have been in the famous photo taken in Barrack 56 in Buchenwald on April 16, 1945 because, by his own account as written in his book Night, he was in the camp hospital on that date. You can read that page on my website, which I updated 3 years ago, here.

1 Comment

Category Featured | Tags: Tags: Chicago Tribune, Elie Wiesel, Night, Scrapbookpages Blog,

Social Networks: Facebook, Twitter, Google Bookmarks, del.icio.us, StumbleUpon, Digg, Reddit, Posterous.

Thursday, May 10th, 2012

By Carolyn Yeager

copyright 2012 carolyn yeager

The official Holocaust narrative versus Elie Wiesel on what is Auschwitz Liberation Day

The official Holocaust narrative has it that the Red Army did not arrive at the Auschwitz labor camps until January 27th, 1945—where they found some of the barracks burning, and also blown-up crematorium buildings which had housed “gas chambers.” This is the date that is commemorated all over the world as the Liberation of Auschwitz.

The official Holocaust narrative has it that the Red Army did not arrive at the Auschwitz labor camps until January 27th, 1945—where they found some of the barracks burning, and also blown-up crematorium buildings which had housed “gas chambers.” This is the date that is commemorated all over the world as the Liberation of Auschwitz.

However, on page 87 of the novel Night it is stated that the Russians “liberated” the inmates who were left behind at Monowitz (Auschwitz III) on January 20th, two days after the bulk of the prisoners left on the one-day forced march to Gleiwitz, from where they were put on a train to Buchenwald.

______________________

The photograph at right is a still photo from a Soviet propaganda film about the Auschwitz liberation. The clothing warehouses, known as “Canada,” are burning. But who set them on fire? [Author’s note: In January 2014, I wrote in an article published here: The photograph at right, a still from a Soviet propaganda film about the Auschwitz “liberation,” had been thought to be of the clothing warehouses burning. But new research suggests it is more likely regular barracks, probably in Compound B1. If this is true, it makes little difference when the picture was taken, as it was certainly after the Russians arrived.]

___________________________________________________________________________________

I included this detail in Night #1 and Night #2, Part Two under the heading “A record of fact it isn’t.” For the first time I’ve seen anywhere, I pointed out this sentence from Elie Wiesel’s book Night:

A strange detail … is on page 87 of the original Night. Eliezer remarks, after his and his Father’s deliberations and final decision to go on the march: “I learned after the war the fate of those who had stayed behind in the hospital. They were quite simply liberated by the Russians two days after the evacuation.” The evacuation, as we all know, was on the 18th. We also know the Russians did not arrive on the 20th of January! The actual liberation day is January 27. What possessed Wiesel to write this? Well, because it was in Un di velt: “Two days after we had left Buna, the Red Army occupied the camp. All the sick had stayed alive.”

It’s important to keep in mind that the Jan. 20th liberation originally appeared in Un di velt hot geshvign, the Yiddish book published in 1955 from which La Nuit was born in 1958 (with the English version Night following in 1960). Whether or not Elie Wiesel is the author of the Yiddish book, there is no doubt that he wrote La Nuit directly from it. So he either wrote that sentence in Un di velt or he copied it from Un di velt for La Nuit. In any event, he has never rejected that sentence as a mistake, nor was it changed in Marion Wiesel’s 2006 translation … perhaps because it appears in the Yiddish Un di velt.

What is the official narrative and what is its source?

There is no easily determined source for the narrative. It consists of the story that the Germans returned to Birkenau on Jan. 20th to blow up Crematorium II and III in order to destroy the evidence of the “gas chambers.”

According to web-based Holocaust Research Project:

On 20 January 1945 an SS division under SS–Corporal Perschel destroys Crematorium II and III and abandons the camp. On 26 January an SS squad blows up Crematorium V, the last of the crematoriums in Birkenau.

An entire division was required to explode two measly crematorium buildings?! I guess what they’re trying to say is that an SS team returned to Birkenau, after the bulk of the prisoners had been evacuated and before the Russians first arrived, to destroy the “evidence.” In other words, they didn’t plan well enough to do it ahead of time so had to sneak back after they had already abandoned the camp. But wouldn’t the ex-prisoners who remained in the hospital buildings that were very close to Crema II and III have heard and seen the explosions? Yes, of course they would, although we don’t have any statements of hospital patients about a demolition in the camp on January 20th.

On Nizkor we find this timetable (source unknown):

“January 20 [1945] … The SS division under Corporal Perschel blows up the already partly demolished Crematoriums II and III and abandons the camp.”

“January 23 [1945] … An SS division arrives in the prisoner’s infirmary camp in B-IIf in the afternoon…they set 30 storeroom barracks [the “warehouses”-cy] in the personal effects camp on fire…. These barracks burn for several days. After the liberation, 1,185,345 pieces of women’s and men’s outerwear, 43,255 pairs of shoes, 13,694 carpets, and a large number of toothbrushes, shaving brushes, and other items such as protheses, glasses, etc., among other things are found in the six remaining partially burned barracks.” [Note: The warehouse barracks were right behind the hospital barracks, where most of the remaining prisoners were staying.]

“January 26 [1945] … At 1:00 A.M. the SS squad with the task of eliminating the traces of SS crimes blows up Crematorium V, the last of the crematoriums in Birkenau.”

“January 27 [1945] …The first Red Army reconnaissance troops arrive in Birkenau and Auschwitz at around 3:00 P.M. and are joyfully greeted by the liberated prisoners….

[Note: If the clothing warehouses were set on fire on Jan. 23, would they still be burning on Jan. 28, 29, 30… however long it took the Soviet movie makers to get there?-cy]

Above: Underneath the roof of the dynamited Crema II in 2005. Below: Ruins of Crema III taken at the same time (Photos courtesy of Scrapbookpages.com)

Above: Underneath the roof of the dynamited Crema II in 2005. Below: Ruins of Crema III taken at the same time (Photos courtesy of Scrapbookpages.com)

In Danuta Czech’s Calendarium [Auschwitz Chronicle 1939-1945, Henry Holt, 1990, 855 pp], probably the source of the above, Czech has the final destruction of Cremas II and III taking place on January 20, 1945. Her basis for that are two “eyewitnesses”—female prisoners Anna Kowalczyk and Maria Matlak—who had remained behind and who said that they “saw” the SS in the camp on that day, and from them came the name of SS-Unterscharführer Perschel, who had been “capo of the Work Service in the women’s camp”, so they knew him. These two women said that after ordering 200 women outside the camp gates to be shot (!), Perschel selects a group of male prisoners from the infirmary (!) to carry boxes of dynamite to Cremas II and III. This is the entire basis for Czech’s claim that the SS returned on Jan. 20th and blew up the Cremas! This is what the Holocaust Industry passes off as proof.

The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum uses Czech’s timeline, but leaves out the Jan. 20-26 demolition dates.

USHMM’s Chronology of the Holocaust

JANUARY 17, 1945

As Soviet troops approached, SS units evacuated prisoners in the Auschwitz camp complex, marching them on foot toward the interior of the German Reich. The forced evacuations came to be called “death marches.”

JANUARY 27, 1945

Soviet troops liberated about 8,000 prisoners left behind at the Auschwitz camp complex.

I did not find anything on the Auschwitz-Birkenau website either. So one thing is clear: these dates about the SS divisions returning to blow up and burn down “evidence” are not sourced in documents. No order has been produced, and there would have to be an order. The SS troops couldn’t just do whatever they decided on their own. The witness statements are of dubious value, to say the least. Thus, there is no reason to believe the “Germans-blew-up-the-Cremas-to-hide-evidence-of-crimes” story, except that it became part of the official narrative that was constructed at Nuremberg. It is held .. it is believed … it is thought … but it is not proved.

What does a January 20th liberation mean?

A January 20th liberation by the Soviets means the Germans could not have returned to blow up the crematorium buildings, nor could they have burned down the clothing warehouses. It means that only the Soviets could have done it—because only the Soviets had the opportunity to do it.

Would they do such a thing if they really held “evidence of German crimes” in their hands … in the form of real gas chambers? Certainly not. It was because there was no evidence of German crimes in those buildings. It was to cover up the lack of German crimes that they would destroy the buildings. They reasoned (in their sly, dishonest minds) that the best course would be to invent German crimes, which they had already been doing since 1941 (and the Polish Resistance had been spreading gassing rumors since 1942), and to simply add the destruction of the buildings by the SS to their list of “German crimes.”

I came across an exchange between two revisionists that took place in 2005. It went like this:

1st revisionist: For me, it seems more plausible that the Soviets (or some other party) destroyed the crematoriums after the war to support their alleged story of genocide. Then they were able to spread this story: “Why would the SS have destroyed the cremas, if not to cover for mass homicide.”

2nd revisionist: I agree with you totally. I also believe the Russians blew them up to destroy the solid evidence that would contradict the lies they were cooking up and about to release on the world.

From the time the Red Army arrived, Soviet Intelligence was in total control. None of the other Allies were allowed to enter this region. In 1947, the Soviets rebuilt the crematorium in Auschwitz I to make it appear that it was used as a gas chamber. Even so, it is not a convincing job. In Birkenau, it was easier to destroy the crematoriums and tamper with them (such as breaking holes into the collapsed roof to match the absurd story of Zyklon B thrown into the chamber through the holes in the roof.) About these chiseled-out holes, court-certified expert engineer Walter Luftl, as quoted by Germar Rudolf in his book Lectures on the Holocaust (Theses and Dissertations Press, 2005), p 246, said:

In the cellars of Crematories II and III, the entire force of explosion was forced upward, causing heavy damage to the roofs. The hole under consideration is characterized by the fact that all the cracks and breaks of the slab are found around it, but do not go through it! According to the rules of construction technology this fact alone proves with scientific certainty that it was made after the roof had been destroyed.

Photo documentation and literature of what the Russians found is scarce.

Why is it that the earliest photo that exists of the destroyed Crema II is this one from February 1945? Why is there no photograph from the time the Russians arrived in January, since such a picture would have much greater propaganda value? To properly document such an important discovery—that the Germans had blown up evidence of crimes as they retreated—many photographs would need to be taken. What happened? Did they run out of film?

Why is it that the earliest photo that exists of the destroyed Crema II is this one from February 1945? Why is there no photograph from the time the Russians arrived in January, since such a picture would have much greater propaganda value? To properly document such an important discovery—that the Germans had blown up evidence of crimes as they retreated—many photographs would need to be taken. What happened? Did they run out of film?

As Tom Moran noted on the Nizkor page linked to above: “It is written the Soviets installed an “Extraordinary Commission” the very day of liberation of the camp and yet no photos are presented on the Holocaust promotional circuit of these buildings, or what was left, lest of course the one and only photograph of Crema II which is nothing more than a collapsed slab of concrete.”

In Photographing the Holocaust: Interpretations of the Evidence (Tauris & Company, London, in association with The European Jewish Publication Society, 2004) on page 143, author Janina Struk writes:

On 28 January, 1945, the day after the camp was liberated by the Red Army, Adolf Forbert was one of the first Polish soldiers to arrive. He described his first impression of Auschwitz as being as “macabre” as Majdanek but on a larger scale.

On 28 January, 1945, the day after the camp was liberated by the Red Army, Adolf Forbert was one of the first Polish soldiers to arrive. He described his first impression of Auschwitz as being as “macabre” as Majdanek but on a larger scale.

Forbert stayed to film everything he could, but with only 300 meters of film, a camera of the Bell and Howell type manufactured by the Russians, and one Leica, the possibilities were limited.

He said there were 500 sick women in the women’s hospital in Birkenau. The fate of Forbert’s film and photographs of Auschwitz is not known.

The film “Chronicles of the Liberation of Auschwitz,” made in 1945, is attributed to four Soviet army filmmakers. The majority of the now well-known stills of the liberation are taken from this film.

Soon after liberation, other photographers began to arrive to take photos for the special investigative commissions established to collect evidence of Nazi crimes.

(Barbie) Zelizer [author of books on the Holocaust and Media -cy] states there was an inconsistency in the way the Soviets reported the liberation of the camps in Eastern Europe generally. Not only did they not publicize the liberation of Auschwitz until after the liberation of the western camps, but they didn’t issue press releases about the extermination camps at Belzec, Sorbibor and Treblinka.

Although their [Red Army] advances through Silesia were reported in detail, there were only two brief mentions about the liberation of the camp. On 29 January in the Guardian, one sentence. On 3 February, the Daily Express had one column on page 4 about the liberation.

In Poland itself, few images were published of the liberation of Majdanek or Auschwitz-Birkenau.

It would be decades before images of Auschwitz would become familiar in the West.

There is almost nothing in Holocaust literature on the arrival of the Soviets to Auschwitz-Birkenau. The only documentation was put together afterward. All the photographs that are exhibited in the various memorial museums (USHMM, Yad Vashem, A-B Memorial & Museum, etc.) and in books, are “stills” from a propaganda film(s) made many weeks or months later … or they are retouched photos, photo-montages and mis-labeled photos that actually show other places and even other national-ethnic groups.

The narrative of a January 27th liberation comes unraveled when scrutinized

Why all the deception? Why all the trickery? The arrival of the Soviets on Jan. 20 instead of Jan. 27 explains it. The person who runs Scrapbookpages Blog and calls himself “furtherglory” once wrote this to a commenter on his blog:

I have read in several books that the Soviets arrived in the area on January 17, 1945 and were in the area for 10 days before they “liberated” the prisoners on January 27, 1945. I have read at least one Holocaust survivor book which said that the warehouses were still there after the Germans left on January 18, 1945. I believe that the Soviets burned down the warehouses. With all the evidence gone, no one could dispute the Soviet testimony at the Nuremberg IMT that 4 million people had been killed at Auschwitz.

The Central Sauna building at Birkenau was kept off limits to tourists for 60 years. Why? The Sauna building was where the clothes were disinfected. Why weren’t tourists allowed to know that the Germans were trying to prevent typhus epidemics?

Also, keep in mind that the last group of Sonderkommandos were marched out of the Birkenau camp and I think a couple of them are still living. Why did the Germans allow these witnesses to live?

Cremas IV and V were also shower houses with hygiene facilities for disinfection. They were close to The Central Sauna and served the same purpose although on a smaller scale. Consider that if the only shower facility in the entire camp was the rather modestly-sized one in The Sauna building, it would not have been at all adequate. But with “Cremas IV and V” also serving that function, they got by. Crema IV was heavily damaged in an uprising on Oct. 7, 1944. Both were ultimately totally destroyed, but the question remains—by whom?

The answer has to be by the Russians themselves. And it is Elie Wiesel who has told us. Just as with his failure to mention “gas chambers” in his book Night, Wiesel falls out of step with the official storyline at times and lets the truth slip out. Was he just saying what most people knew at the time, in spite of what was dreamed up at Nuremberg? I think so. He wrote this in 1954. Not even Elie Wiesel should confuse 9 days with 2 days when it comes to a matter of life or death. Which brings up another question: Is it reasonable that the prisoners left behind in an unguarded facility would just hang around for nine days waiting for the feared “Red Army” to arrive? Would they not take off once they got the chance? Elie says he was one of the hospital patients, his father being allowed to stay with him, yet they both were capable of going on the evacuation march and keeping up with the pace. Thus, many others lying around in the hospital surely could do the same. That is, unless the Soviet representatives surprised them by showing up already on the 20th, before they could prepare themselves to leave.

The story of the Auschwitz liberation is as cloudy as it gets. It has been told in emotion-wrenching photographs that were all staged by Soviet photographers and film makers in the following month of February and even March–every one of them–and by revengeful witnesses who were coached in what to say. As portions of the book by Janina Struk point out, time would pass before a final solution of what happened at Auschwitz could be cobbled together for public consumption by Soviet propagandists.

20 Comments

Category Featured | Tags: Tags: Auschwitz Liberation, Crematoriums II and III, Elie Wiesel, Night, Un di velt hot geshvign,

Social Networks: Facebook, Twitter, Google Bookmarks, del.icio.us, StumbleUpon, Digg, Reddit, Posterous.

Wednesday, March 7th, 2012

By Carolyn Yeager

copyright 2012 Carolyn Yeager

Elie Wiesel questioned under oath in a California courtroom in 2008:

Q. And is this book Night that you wrote a true account of your experience during World War II?

A. It is a true account. Every word in it is true.

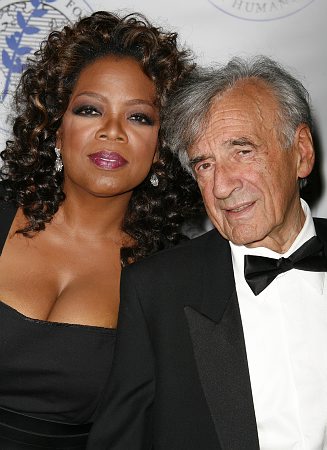

Elie Wiesel manning his table at a Jewish book fair in Austin, TX, 2006. The new translation of Night by his wife Marion had come out in January of that year, and it was immediately chosen for Oprah Winfrey’s book club.

In Part One, I established that the decision to rebrand Night into an autobiography was the reason for a new translation, in which necessary changes could be made to better ‘fit’ the story both to the real Elie Wiesel and the known facts of the Hungarian deportation.

When the 2006 translation came out, with its new classification to “autobiography,” questions arose from some circles. Responding to these questions, Edward Wyatt wrote an article in the NewYork Times on Jan. 19, 2006, in which he quoted Jeff Seroy, senior vice president at Farrar, Straus & Giroux, parent company of Night publisher Hill & Wang, as strongly denying that changes were made to bring the book more in line with the facts. “Nonsense,” said Seroy. “Some minor mistakes crept into the original translation that were expunged in the new translation. But the book stands as a record of fact.”

Blaming the Translator

“Mistakes in the original translation” can only mean mistakes by Stella Rodway, the original translator! But we have already shown that Stella Rodway faithfully reproduced the French La Nuit, which was Wiesel’s own work. The author and publisher are casting these changes as translation errors to divert attention away from Elie Wiesel’s own errors—part of their campaign to pass Night off from now on as “a record of fact.”

Publisher Jeff Seroy, center, with writer Brad Gooch to his left, Doug Stumps on his right .

A record of fact it isn’t

When I ended Part One, Eliezer and Father were still in the train car on their way to Buchenwald. You will recall that the Yiddish, the French and thus the original English version of Night specified the trip took 10 days and 10 nights from Gleiwitz (on the former German/Polish border) to Buchenwald. Since we know from standard historical sources1 that the prisoners were evacuated from Monowitz on Jan. 18 and arrived in Gleiwitz the next day, Jan. 19; and since according to the description in Night itself, they spend three days in Gleiwitz (Jan. 20-22), this would make their day of arrival February 1, 1945. But in Night, Father’s death takes place the night of Jan. 28-29, three days before they arrived! This is why Marion Wiesel removed the number 10 in her new translation, leaving the number of days and nights undetermined.

A strange detail that actually belongs in Part One is on page 87 of the original Night. Eliezer remarks, after his and his Father’s deliberations and final decision to go on the march: “I learned after the war the fate of those who had stayed behind in the hospital. They were quite simply liberated by the Russians two days after the evacuation.” The evacuation, as we all know, was on the 18th. We also know the Russians did not arrive on the 20th of January! The actual liberation day is January 27. What possessed Wiesel to write this? Well, because it was in Un di velt: “Two days after we had left Buna, the Red Army occupied the camp. All the sick had stayed alive.”

From the point in the story of Eliezer and Father’s arrival at Buchenwald there are no significant changes made by Marion Wiesel to the original French and English versions. But there is much in all the versions that differs strikingly from the “official holocaust history” as written by acknowledged official chroniclers such as Danuta Czech. So I will continue with comparisons between Night and “official history,” along with some very significant changes made from Un di velt hot geshvign to Wiesel’s edited French La Nuit.

Arrival at Buchenwald: 26 Jan. or 1 Feb.?

Danuta Czech, in her Auschwitz Chronicle1, records that on January 26,

Danuta Czech, in her Auschwitz Chronicle1, records that on January 26,

A transport with 3,987 prisoners from Auschwitz auxiliary camps reaches Buchenwald. There are 52 dead prisoners in the transport. 115 prisoners die on the day of arrival. Their corpses are delivered to the autopsy room. (P 801)

This is the transport that carried Lazar and Abraham Wiesel/Viezel, Miklos (Nikolaus) Grüner and all of the inmates of Monowitz whose names are on the transport list.2 According to Czech, the Monowitz prisoners began their march on the evening of January 18, 1945, with “divisions of nurses placed between the columns” of 1000 each (P 786), arriving at Gleiwitz Camp the following evening. On Jan. 21 “they are loaded in open freight cars with other prisoners from Auschwitz who have arrived in Gleiwitz.” (P 788) From Jan. 21 to Jan. 26 is five days of travel … not ten, as Wiesel wrote in Night.

The narrative in Night gives us a date of Jan. 22 for the boarding of the train, one day later than Czech. And while Night gives the number of days on the train (10), it does not name the date of arrival.

Hilda Wiesel says her father died on arrival

Totally contradicting what is written in Night, Hilda Wiesel Kudler, Elie’s oldest sister, in her testimony for the Shoah Foundation in 1995, said she learned from her brother that their father died as he stepped off the train.

Hilda Wiesel Kudler, in France, giving her videotaped testimony to the Shoah Foundation