Does Elie Wiesel speak Hungarian?

Thursday, March 21st, 2013

By Carolyn Yeager

copyright 2013 carolyn yeager

The answer might be: Barely. Or rudimentarily.

The answer might be: Barely. Or rudimentarily.

Elie Wiesel is known for putting big ones over on the American (and other English-speaking) people, so it is no surprise to us that he is also faking his knowledge of Hungarian. I had already noticed that, on the rare occasions he is shown speaking that language, he doesn’t go beyond short phrases or even just one-or-two-word questions and answers. Not being linguistically gifted myself, I didn’t feel I could say much about it.

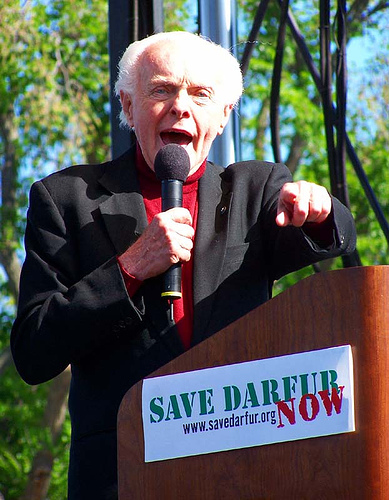

Image right: The pretentious Tom Lantos Human Rights Prize for 2010 was presented to the pretentious Elie Wiesel (shown with Lantos’ widow) in November 2010. [Photo by Babette Rittmeyer & Brittany Smith] More about Tom Lantos below.

But now a Hungarian-American reader named John contacted me about the video “Elie Wiesel Goes Home.” He began by watching the short segment (2 min 29 sec) that is available on Youtube. He noticed discrepancies right away.

According to John:

Wiesel is speaking Hungarian words, but they are not spontaneous and his “inflections” are all wrong. The person he is speaking with IS speaking spontaneously, with proper Hungarian (very language specific) inflections, and using the proper idiomatically correct sentence structures. Wiesel is speaking in a short, pressured, and monotone manner – more like if a foreign-born person would have studied a travel guide.

Also, Wiesel’s accent while speaking English is not like a native Hungarian who is speaking English. Listen to former Senator Tom Lantos – he was from Hungary and also of Jewish descent; his accent, while speaking English, has the distinctive Hungarian characteristics that I am familiar with.

John told me why he thinks he is a competent judge of Wiesel’s language skills:

I was born in Hungary and escaped from there in 1956. I am fluent in Hungarian (without any accent) and I am fluent in English (without any accent). I was educated both in the U.S. and (some) in Europe, I have traveled a lot and I understand “cultural idioms.”

In his first message to me, John detailed a few translation errors in the video segment.

Video captions vs. the correct translation:

@48 seconds into the video the caption reads “This is the most important” – the correct translation is “This is the most interesting”@ 54 seconds into the video the caption reads “A farewell letter. When they knew they’d be taken away.” – the correct translation is: “This is a farewell letter, [written] while they were already waiting, to take them away”

@ 57 seconds into the video the caption reads “I had a Christian employee” – the man simply says “I had an employee.”

John then did an exact word for word comparison of the captions on the film segment versus what was actually spoken between the two men. The Hungarian is showing some family photos to Wiesel as they speak. What we notice is that Elie Wiesel said very little, and at times the Hungarian man didn’t seem to understand Wiesel’s words. In order to demonstrate that, I will now copy just the actual words that passed between the two, leaving aside the captions. Wiesel’s speech is in blue boldface.

My brother’s family. You said you knew them?

Yes.

This is with his wife. His children, my oldest brother, who might have known you. [Note that Wiesel does not answer.-cy]

And, ah, did they go to Auschwitz?

What’s that?

They went to Auschwitz.

Everyone. They don’t exist to anyone. I would remember. They don’t exist.

This is my mother.

Mother. Did she die here in Sighet or Auschwitz?

Iske died in Sighet, she lived until ’34.

This is our entire family … as we were [as all of us that were around].

And this?

This. This is the most interesting. This … is a farewell letter, while they were already waiting, to take them away.

Yes.

Then … I had an employee … [Wiesel interrupts as if he doesn’t know what was said about the employee.-cy]

They didn’t know about Auschwitz.

They didn’t know, of course no one knew, and it came to us [later] what was to be.

Then they, the children, wrote me a farewell letter, because they knew then that … I had sent the man from the forests to find out what’s going on … [“forests” could refer to a region, i.e. Transylvania in Hungarian is “Erdély” meaning “The Forests” – John] and afterwards, on the last day, they sent me this letter — that the children, he, his wife and my father say farewell to me.

This is very important.

Yes.

Wiesel turns to one of his crew near him and says in English: “This is a collective letter of farewell that the entire family wrote to him the day of the deportation, this is very important.”

This is very important.

Yes. From the content you’ll see —

Exactly.

what kind of mood, sadness, they didn’t know what was going to happen … they were sitting on their luggage and waited for them to come … poor things … and then, well, the rest of it we already know … we didn’t know what would be desired to happen, or what will happen. I told all of this stuff to Militka in English.

No one came back?

What?

No one came back?

No one in the world.

No one.

There would still be a lot more, but these are the most important. I am very happy for this because it would have been lost.

This … it was left.

It is clear from this that Wiesel’s part in this conversation consists of very few words, spoken repetitively. Add to this the claim by Nikolaus Grüner that Wiesel declined to speak with him in Hungarian when they met in Stockholm in 1986, and other situations wherein Wiesel had the opportunity to show off his Hungarian but didn’t … and we have to assume that he is simply unable to speak it with any fluency.

What else can explain Elie Wiesel’s lack of understanding of the Hungarian language?

As I have written in earlier articles, Elie Wiesel did not like public secular school, but he loved Jewish religious school. As a youth, he often played sick and missed school. Yiddish was the common language spoken in the home and in the community. Wiesel learned Hebrew and devoted himself to the Talmud and other Jewish religious texts. He did not like Gentiles and avoided them; Hungarian was the language of the enemy. Later, at age 17 (or earlier?) he went to France and became a French speaker.

But why doesn’t he just say so? Why does he prefer to give people a false impression about himself? Is this just another aspect of his need to lie — to make up stories, to see that which didn’t happen as if it did happen, and that which did as not having happened? Is Elie Wiesel just an inveterate, or compulsive, liar?

“Holocaust survivors” are mostly people who tell lies. The late Senator Tom Lantos (below left) is a good example. It turns out that he and Elie Wiesel are the same age — both born in 1928, in February and September respectively, and according to their own accounts (no other confirmation) were arrested in Spring 1944 in the Jewish round-up in Hungary. Wiesel says he was sent to Auschwitz and got tattooed, along with his father. Lantos tells a different story.

Is there any reason to believe the story Tom Lantos tells of being a “holocaust survivor?”

Is there any reason to believe the story Tom Lantos tells of being a “holocaust survivor?”

Tom Lantos was born in 1928 (same year as Elie Wiesel) to a Jewish family living in Budapest. According to his Foundation biography, “as a teenager he was sent to a forced labor camp by the German Nazi occupant military. After escaping the labor camp, he sought refuge with an aunt who lived in a safe house operated by Raoul Wallenberg …”

Wikipedia (Ref. #8) uses the Biography Channel as the source for Lantos’ holocaust survival story:

In March 1944, [Lantos] was sent to a labor camp in Szob, a small village about 40 miles north of Budapest. He and his fellow inmates maintained a key bridge on the Budapest-Vienna rail line. Lantos escaped, was captured and beaten, then escaped a second time and returned to Budapest.

Do we know that Lantos was not paid for this labor – as so many were – but still “ran away” and returned to Budapest, where he met up with some form of resistance organization? No we don’t. No research has been done; no proof or records of any of this has been presented. It is simply accepted that Tom Lantos is a holocaust survivor and entitled to the sympathy and prestige that accompanies that status, plus payments for life from the “perpetrators.” His Foundation biography continues:

“After the Russians liberated Budapest in 1945, Tom tried to locate his mother and family members but came to realize that they had all perished …”

Tom was in Budapest all that time and didn’t try to locate his mother?! His story is that he was “able to move around freely due to his having blond hair and blue eyes, which to the Nazis were physical signs of Aryanism” … as if the German police were even in Budapest and, if they were, would be unaware that Jews could also have blond hair and blue eyes. “As a result, he acted as a courier for the underground movement and delivered food and medicine to Jews living in other safe houses.” Naturally, he is presented as a positive figure, similar to Max Hamburger.

There is nothing finally said about what befell his family members, yet Wikipedia states, without any source or reference whatsoever, that “his mother and other family members had all been killed by the Germans, along with 450,000 other Hungarian Jews during the preceding 10 months of their occupation.” Believable? The source of all this can only be Tom Lantos himself, who has already been outed (by Eric Hunt, for one, in his film “The Last Days of the Big Lie“) as a practiced liar in hearings about Iraq on Capitol Hill. But heck, we all know …

His experiences in the Holocaust and afterward were highlighted in the Academy Award winning documentary The Last Days (1998) produced by Steven Spielberg‘s Shoah Foundation.

Some things we can learn from all this:

- Sixteen-year-old boys in Hungary were just as likely to be sent directly to nearby labor camps, and not to Auschwitz, in which case they would NOT have been tattooed with an Auschwitz camp number. This could explain something about Elie Wiesel.

- It was not too difficult in 1944 to escape custody and join the “resistance” without being discovered, especially if you had close relatives who had managed to avoid deportation.

- These 16-year-olds had fathers, mothers and siblings that were also capable of work, but supposedly were not sent to labor camps as Tom Lantos was, but for some unexplainable reason to Auschwitz to be killed. In any case, it is always said that none survived.

Category Featured | Tags: Tags: "Elie Wiesel Goes Home", Auschwitz, Budapest, Elie Wiesel, Hungarian language, Tom Lantos,

Social Networks: Facebook, Twitter, Google Bookmarks, del.icio.us, StumbleUpon, Digg, Reddit, Posterous.