When did Elie Wiesel arrive at Auschwitz? Could he have received the number A-7713?

Thursday, January 19th, 2012

By Carolyn Yeager

copyright 2012 carolyn yeager

Fact is–it’s a deliberately confusing story with two distinct versions. Originally, he was too late to be assigned that number; in a newer rewrite, he was right on time. Which would you believe?

Above: Hungarian transport arriving at Auschwitz-Birkenau in 1944. Notice the casual atmosphere, the inmate-workers in striped clothing (not wielding clubs), the non-threatening guards spotted here and there (without snarling dogs), and the crematorium chimney in the distance — which is not belching smoke and fire.

UPDATE: (Jan. 30) It’s worth taking a closer look at the female deportees in the background who are accepting the arrival process in quite a different manner than what we always hear in the official stories of the Hungarian Jews. And from the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, I might add, which is a big pusher of the Hungarian Jewish “extermination.” These women don’t look too much the worse for wear from their trip. Three of them are smiling, two are also waving to someone they know, perhaps the person in the lower left questioning the officer. How can they be so cheerful, you might ask? A good question.

UPDATE: (Jan. 30) It’s worth taking a closer look at the female deportees in the background who are accepting the arrival process in quite a different manner than what we always hear in the official stories of the Hungarian Jews. And from the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, I might add, which is a big pusher of the Hungarian Jewish “extermination.” These women don’t look too much the worse for wear from their trip. Three of them are smiling, two are also waving to someone they know, perhaps the person in the lower left questioning the officer. How can they be so cheerful, you might ask? A good question.

______________________________

At the very end of my recent article The Truth About Night, I wrote:

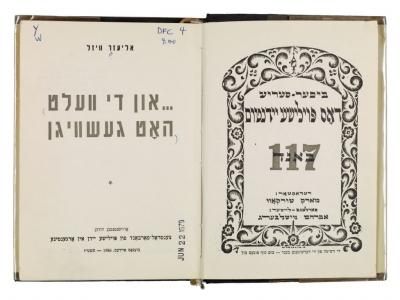

My challenge: I welcome any native Polish Yiddish speaker/reader who is also fluent in English to prove me wrong about what I have written above by providing an honest, accurate translation of Un di Velt Hot Gesvign [And The World Remained Silent] into English so it can be compared with Night. Why hasn’t this already been done? It’s natural to be suspicious of what is kept hidden. Let’s put everything on the table so that the questions I have raised can be cleared up.

Though I had no real hope of that, I was most happily surprised when a gifted linguist using the name “Kladderadatsch” appeared on the Codoh Forum with a professional translation of a section from the Yiddish book. You can go to that thread (begin on page 4 of “Is This the End of Elie Wiesel?”) to see all the translations he has posted there so far. I have copied his last post/translation/analysis as the main element of this article, but first I want to give a short introductory comment.

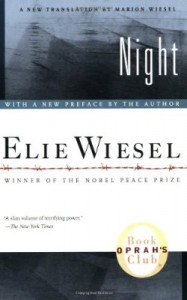

When retranslating Night for its 2006 publication, Marion Wiesel (working with Elie and whoever else) made numerous changes in the wording of the original translation. An important, but hard-to-notice change was her rearrangement of the wording for the deportation dates of the Wiesel family. She connived to move their arrival date at Auschwtiz back two whole weeks. By doing so, she made it possible for young Eliezer to be given the registration number A-7713 on May 24, 1944, the day it was given out according to the transport records published by Randolph Braham1 and available at the Memorial Museum of Auschwitz-Birkenau. (More on Braham further down)

In the original LaNuit/Night published in 1958/60, and in Un di velt hot geshvign, published in 1956, the Wiesel family arrived at Auschwitz 3 days after their departure on June 3, 1944, making it approximately June 6th, well after the registration numbers A-7712 and 7713 had already been assigned. Therefore, as the story was originally written, the going-on-15-year-old Eliezer Wiesel could not have been registered with that number.

The analysis by ‘Kladderadatsch’ posted on Friday, Jan. 13:

Dates.

According to Mattogno, citing microfilm records from the Auschwitz museum (“Liste der Judentransporte, Museum of Auschwitz-Birkenau, microfilm no. 727/27,” Mattogno’s footnote 15), the Auschwitz registration number A-7713 was assigned on May 24, 1944. In his article, Mattogno makes the case that this means Elie Wiesel could not have been assigned A-7713 because he would have arrived at Auschwitz after that date:

Elie Wiesel does not specify the date of his deportation to Auschwitz. His narrative starts, though, with reference to a specific date: “On the Saturday before Pentecost [“Shavuòth” in the Italian edition], in the spring sunshine, people strolled, carefree and unheeding, through the swarming streets.” (p.22-23). In 1944, this festival fell on 28 May 1944 [14], a Sunday. The day in question was thus 27 May. The first transport of Jews left Sighet on the following day, hence, on 28 May. “Then, at last, at one o’clock in the afternoon, came the signal to leave” (p.27). Elie Wiesel then speaks of “Monday” (p. 29), the dawn (p.29), the day after tomorrow (p. 29) saying, at the end, “Saturday, the day of rest, was chosen for our expulsion” (p. 33) He then speaks about the traditional Friday evening meal and goes on to say: «The following morning, we marched to the station […]» (p. 33, which means that the trip to Auschwitz began on Saturday, 3 June 1944.

The duration of the trip is not given, but transports from Hungary usually took three or four days to reach Auschwitz-Birkenau. Elie Wiesel spent the night at Birkenau and was moved to Auschwitz the following day where he was given the number A-7713, which was tattooed on his arm (p. 54). Yet, according to him, “it was a beautiful April day” (p. 51).

This schedule is pure invention. If he did leave Sighet on 3 June 1944 he could not have arrived at Auschwitz in April. Moreover, the ID number A-7713 was given out on 24 May, the day on which 2,000 Hungarian Jews were assigned the numbers A-5729 through A-7728 [15]. According to Randolph L. Braham, a Jewish transport left Máramarossziget on 20 May 1944.[16] Allowing four days for the journey, this was the transport of Lázár Wiesel who was assigned the ID number A-7713 precisely on 24 May 1944. But apparently, Elie Wiesel was unaware of all these things.

[15] Liste der Judentransporte, Museum of Auschwitz-Birkenau, microfilm no. 727/27.

[16] R.L. Braham, A Magyar Holocaust. Gondolat Budapest-Blackburn International Inc.,Wilmington, 1988, p. 514.

That seems pretty conclusive.

On the other hand, however, Carolyn Yeager’s article about the various Wiesel signatures makes the case that Wiesel must have been deported from Sighet on May 20, 1944:

In the “revised and updated” new translation of 2006, Wiesel gives his family’s date of deportation to the “small ghetto” as May 17, 1944. I arrive at this date because Wiesel writes that it was “some two weeks before Shavuot” (Shavuot fell on May 28 in 1944) that the deportation order was announced to his family and neighbors. [Remember, Sighet had 90,000 residents, at least one-third of them Jews, while Wiesel makes it sound like he lived in a little village.] Departures were to take place “street by street” starting the next day. That would be May 15. But the Wiesel family was scheduled to leave in the 3rd group, which left two days later, on May 17. After being marched to the “small ghetto,” they stayed there “a few days.” On a “Saturday,” they boarded trains.5 The 20th of May, 1944 was a Saturday.

If Mattogno is correct that “transports from Hungary usually took three or four days to reach Auschwitz-Birkenau,” which seems probable, and if Wiesel’s transport departed on May 20, then it’s entirely possible for him to have arrived on May 23, spent the night at Birkenau, and then been marched over to Auschwitz on May 24 to get his prisoner number, A-7713 . . . exactly like Wiesel has always said.2

Now I’m pretty sure Carolyn wasn’t looking to prove that Wiesel’s claim to number A-7713 is legitimate (her focus in the article is actually on discrepancies in various arrest dates in the later Buchenwald paperwork), but if her reconstruction of the deportation’s timing is correct, that’s what she’s done.

So who’s right, Mattogno or Yeager?

Both, probably. The problem, of course, is that Wiesel is a moving target. Mattogno is using the original edition of “Night,” as translated by Stella Rodway. And sure enough, in that version it says “On the Saturday before Pentecost . . . ” But the “revised and updated” 2006 translation, which Carolyn quotes in her article, says “Some two weeks before Shavuot.” Since Pentecost and Shavuot are the same thing (Rodway just uses the more familiar term for non-Jewish readers, “Pentecost” being the name of a Christian holiday as well), that means that we have two possibilities:

1) Saturday before Pentecost/Shavuot,

2) an unspecified date “some two weeks before.”

As Mattogno and Yeager both note, Shavuot was on May 28 in 1944 (it’s easy to check), a Sunday. So counting backwards, “the Saturday before Pentecost” (May 28) gives May 27, and “two weeks before” gives May 14. In one case, the dates make it impossible for Elie Wiesel to have been assigned A-7713, in the other, they line up perfectly.

ing of 1945?

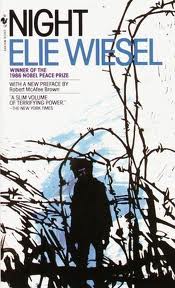

Above Left: Original Night, 1960, paperback. Right: Marion Wiesel’s 2006 new translation, recommended by Oprah Winfrey.

So here’s a situation where determining what the original text really says is important. Someone reading Mattogno’s article and then checking the most recent “revised and updated” edition of “Night” might just conclude that he’s dishonest–the text there doesn’t say “the Saturday before,” it says “some two weeks before.” Sheesh. And someone reading Carolyn’s article, with Mattogno’s in mind, might conclude that while she may start from the “correct” premises (again, according to the “revised and updated” version!), she really just shoots herself in the foot by proving that Wiesel left Sighet on May 20, exactly the right date for him to be on the transport recorded by Randolph Braham and to arrive in Auschwitz on May 24 to receive prisoner number A-7713. Is Mattogno lying? Can Carolyn not shoot straight?

Or could it just be that Wiesel is covering his tracks, sowing confusion among revisionists along the way?

“Un di Velt hot Geshwign,” p. 22:

Un azoy zenen teg farlofn, teg velkhe hobn aruntergerisn bleter fun kalendar un undz dernentert tsu yenem shwartsn shbth. Vos vet oyf eybik farbleybn in meyn zkhrwn, afilu ven ikh vel zeyn farmshpt tsu lebn bizn letstn tog fun ale teg, oyf der doziker tsby”wthdiker velt.

Geshen iz dos Shbth far Shbw”wth.

A friling-zun hot oysgegosn ir likht un varemkeyt iber der gorer velt un oykh iber geto. . . .

And so the days raced by, days which ripped away pages from the calendar and brought us nearer to that black Saturday [lit, black Sabbath]. Which will remain forever in my memory, even if I were condemned to live to the very last day of days on this deceiving world.

It happened Saturday [Sabbath] before Shavuot.

The springtime sun had spread its light and warmth over the whole world, and even over the ghetto. . . .

(Notice how he says he’ll never forget “that black Saturday” even if he was “condemned to live to the very last day of days.” I guess he might still mix the date up, though, right?)

Anyway, case closed? Well, there’s one last possibility. Jewish holidays are counted from the evening of the day before, and so maybe the Yiddish text is including Saturday, May 27 as part of Shavuot, thus making “Saturday before Shavuot” one week earlier, or May 20. But of course that still doesn’t fix the problem, since that date is just the starting point for the deportation process for the Jewish community: the Wiesel family isn’t relocated to the small ghetto until three days later, and not actually shipped out from Sighet until after several more. Which would mean, of course, that Elie Wiesel could not have been on the transport that left Sighet on May 20, and could not have arrived at Auschwitz by May 24 to receive prisoner number A-7713.

And somebody must have pointed that out to our friend Elie. So the whole thing gets wound backwards by two whole weeks. The text is quietly changed . . . and no one is supposed to notice.

Oh, and by the way, the original really does say “it was a beautiful April day”:

A sheyner April-tog iz es geven. A frilings-rich in der luft.

It was a beautiful April day. A scent of spring in the air.

“Un di Velt,” p. 83

Quietly changed, in 2006, to “It was a beautiful day in May.”

Do you suppose Elie reads Carlo Mattogno?

–end of post

Who is Randolph Braham and how credible is he?

Mattogno writes: “Moreover, the ID number A-7713 was given out on 24 May, the day on which 2,000 Hungarian Jews were assigned the numbers A-5729 through A-7728 [15]. According to Randolph L. Braham, a Jewish transport left Máramarossziget on 20 May 1944.[16] Allowing four days (or three-cy) for the journey, this was the transport of Lázár Wiesel who was assigned the ID number A-7713 precisely on 24 May 1944. But apparently, Elie Wiesel was unaware of all these things.”

[15] Liste der Judentransporte, Museum of Auschwitz-Birkenau, microfilm no. 727/27.

[16] R.L. Braham, A Magyar Holocaust. Gondolat Budapest-Blackburn International Inc., Wilmington, 1988, p. 514.

Braham is a Jewish Hungarian historian whose magnum opus, according to Arthur Butz, is his two-volume work The Politics of Genocide: The Holocaust in Hungary. Braham has written more on this subject than anyone else. The official story is that the entire Hungarian deportation program was carried out between May 15 and July 9, 1944. It started in Ruthenia (Carpatho-Ukraine, annexed from Slovakia) and northern Transylvania (annexed from Romania). The second location is where Sighet is found. A hundred thousand Jews remained in the hands of the Hungarians to be employed in labor battalions (in other words, were not deported).

The USHMM says this about him: Randolph L. Braham is Distinguished Professor Emeritus of Political Science and Director, Rosenthal Institute for Holocaust Studies, Graduate Center of the City University of New York, and Member, Academic Committee of the United States Holocaust Memorial Council. Publication of his two-volume work The Destruction of Hungarian Jewry: A Documentary Account (1963) distinguished Dr. Braham as a pioneer scholar in Holocaust Studies. He is coeditor (with Scott Miller) of The Nazis’ Last Victims: The Holocaust in Hungary (Wayne State University Press, published in association with the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, 1998) as well as author and editor of more than three dozen other works on the Holocaust in central and eastern Europe.

If Elie Wiesel is not prisoner #A-7713, then who is he and where was he between the spring of 1944 and the spring of 1945?

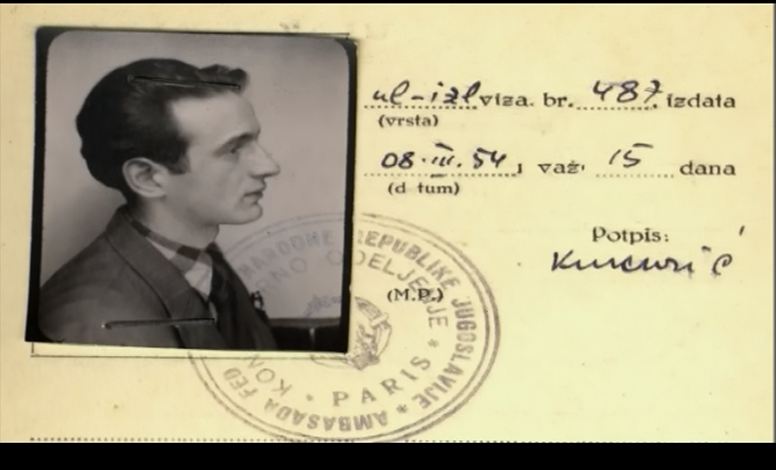

According to all available evidence, Elie Wiesel has falsely placed himself in the concentration camps Auschwitz I, II, III and Buchenwald by assuming the identity documents of Lazar Wiesel, born Sept. 4, 1913, as his own. This cannot be glossed over as a bureaucratic error because there are too many documents involved. Kenneth Waltzer, a professor of German history and Judaic Studies who has written about Elie Wiesel, has put forth this very explanation on this website and at Scrapbookpages Blog (although not on his own websites), but we haven’t heard a word from him in many months. He becomes quieter all the time.

It has been long remarked that Elie Wiesel’s book Night is fiction and does not accurately portray the camps wherein he claims to have been detained. This fictional story is based on a 245-page Yiddish book Un di velt hot geshvign (And the world remained silent), published in 1956 by a Yiddish publishing house in Buenos Aires, Argentina. Night, just 100 pages long, is a condensation of that book. The origins of Un di velt are not known at this time, but Elie Wiesel Cons The World will begin writing comparisons of the original and 2006 versions of Night – comparing them also with as much of the true original Un di velt as we can get hold of. It’s still a very interesting journey we’re on, but the end cannot be far away.

Endnotes:

1. Randolph L. Braham, The Politics of Genocide: The Holocaust in Hungary, two vols. (Boulder, Colorado: East European Monographs, 1993 [revised edition]).

2. In the original Night, it is actually the 2nd day after arrival that Wiesel writes he was tattooed. I will go into that in an upcoming article.

Category Featured | Tags: Tags: Auschwitz #A-7713, Elie Wiesel, Hungarian deportation, Night, Un di Velt Hot Gesvign,

Social Networks: Facebook, Twitter, Google Bookmarks, del.icio.us, StumbleUpon, Digg, Reddit, Posterous.

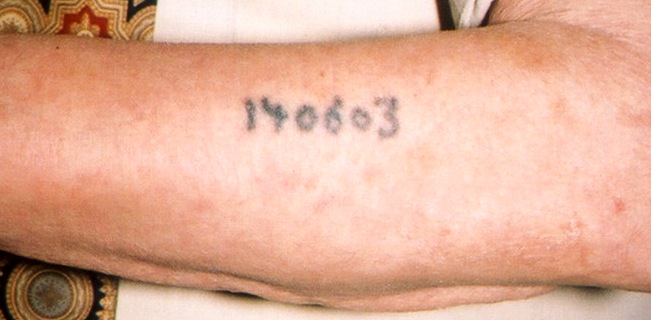

Gruner’s tattoo looks like a real tattoo to me. It looks very similar to the one in this picture at right of Sam Rosenzweig’s arm, which I have posted

Gruner’s tattoo looks like a real tattoo to me. It looks very similar to the one in this picture at right of Sam Rosenzweig’s arm, which I have posted